CHAPTER ONE

It ended with a dream.

Ten years of peace, the ancient Oracle of Asherat-of-the-Sea promised me; ten years I had, and in that time, my fortune prospered along with that of Terre d’Ange, my beloved nation. So often, a time of great happiness is recognized only in hindsight. I reckoned it a blessing that the Oracle’s promise served also as warning, and let no day pass without acknowledging its grace. Youth and beauty I had yet on my side, the latter deepening as the years tempered the former. Thus had my old mentor, Cecilie Laveau-Perrin, foretold, and if I had counted her words lightly in the rasher youth of my twenties, I knew it for truth as I left them behind.

’Tis a shallow concern, many might claim, but I am D’Angeline and make no apology for our ways. Comtesse de Montrève I may be, and indeed, a heroine of the realm—had not my deeds been set to verse by the Queen’s Poet’s own successor?—but I had come first into my own as Phèdre nó Delaunay, Naamah’s Servant and Kushiel’s Chosen, an anguissette and the most uniquely trained courtesan the realm had ever known. I have never claimed to lack vanity.

For the rest, I had those things which I prized above all else, not the least of which was the regard of my Queen, Ysandre de la Courcel, who gifted me with the Companion’s Star for my role in securing her throne ten years past. I had seen then the makings of a great ruler in her; I daresay all the realm has seen it since. For ten years, Terre d’Ange has known peace and abiding prosperity; Terre d’Ange and Alba, ruled side by side by Ysandre de la Courcel and Drustan mab Necthana, the Cruarch of Alba, whom I am privileged to call my friend. Surely the hand of Blessed Elua was upon that union, when love took root where the seeds of political alliance were sown! Truly, love has proved the stronger force, conquering even the deadly Straits that divided them.

Although it took Hyacinthe’s sacrifice to achieve it.

Thus, the nature of my dream.

I did not know, when I awoke from it, trembling and short of breath, tears leaking from beneath my closed lids, that it was the beginning of the end. Even in happiness, I never forgot Hyacinthe. I had not dreamed of him before, it is true, but he was ever on my mind. How could he not be? He was my oldest and dearest friend, the companion of my childhood. Not even my lord Anafiel Delaunay, who took me into his household at the age of ten, who trained me in the arts of covertcy and whose name I bear to this day, had known me so long. What I am, what I became, I owe to my lord Delaunay, who changed with a few words my fatal flaw to a sacred mark, the sign of Kushiel’s Dart. But it was Hyacinthe who knew me first, who was my friend when I was naught but a whore’s unwanted get, an orphan of the Night Court with a scarlet mote in my left eye that made me unfit for Naamah’s Service, that made superstitious countryfolk point and stare and call me names.

And it was Hyacinthe of whom I dreamed. Not the young man I had left to a fate worse than death—a fate that should have been mine—but the boy I had known, the Tsingano boy with the black curls and the merry grin, who, in an overturned market stall, reached out his hand to me in conspiratorial friendship.

I drew a deep, shuddering breath, feeling the dream recede, tears still damp on my cheeks. So simple, to arouse such horror! In my dream, I stood in the prow of a ship, one of the swift, agile Illyrian ships I knew so well from my adventures, and wept to watch a gulf of water widen between my vessel and the rocky shore of a lonely island, where the boy Hyacinthe stood alone and pleaded, stretching out his arms and calling my name. He had solved a riddle there, naming the source of the Master of the Straits’ power. I had answered it too, but Hyacinthe had used the dromonde, the Tsingano gift of sight, and his answer went deeper than I could follow. He won us passage across the Straits when we needed it most and the cost of it was all he had, binding him to those stony shores for eternity, unless the geis could be broken. This I had sought for many years to do, and in my dream, as in life, I had failed. I could hear the crew behind me, cursing in despair against the headwinds that drove us further away, the vast expanse of grey water widening between us, Hyacinthe’s cries following, his boyish voice calling out to the woman I had become, Phèdre, Phèdre!

It shivered my flesh all over to remember it and I turned unthinking toward comfort, curling my body against Joscelin’s sleeping warmth and pillowing my tear-stained cheek on his shoulder—for that was the last and greatest of my gifts, and the one I treasured most: Love. For ten years, Joscelin Verreuil has been my consort, and if we have bickered and quarreled and wounded each other to the quick a thousand times over, there is not a day of it I would relinquish. Let the realm laugh—and they do—to think of the union betwixt a courtesan and a Cassiline; we know what we are to one another.

Joscelin did not wake, but merely stirred in his sleep, accommodating his body to mine. Moonlight spilled through the window of our bedchamber overlooking the garden; moonlight and the faint scent of herbs and roses, rendering his fair hair silver as it spread across the pillows and making the air sweet. It is a pleasant place to sleep and make love. I pressed my lips silently to Joscelin’s shoulder, resting quiet beside him. It might have been Hyacinthe, if matters had fallen out otherwise. We had dreamed of it, he and I.

No one is given to know what might have been.

So I mused, and in time I slept and dreamed that I mused still until I awoke to find sunlight lying in a bright swathe across the bed-linens and Joscelin already awake in the garden. His daggers flashed steel as he moved through the seamless series of exercises he had performed every day of his life since he was ten years old, the training-forms of a Cassiline Brother. But it was not until I had risen and bathed and was breaking my fast that he came in to greet me, and when he did, his blue eyes were somber.

“There is news,” he said, “from Azzalle.”

I stopped with a piece of honey-smeared bread halfway to my mouth and set it down carefully on my plate, remembering my dream. “What news?”

Joscelin sat down opposite me, propping his elbows on the table and resting his chin on his hands. “I don’t know. It has to do with the Straits. Ysandre’s courier would say no more.”

“Hyacinthe,” I said, feeling myself grow pale.

“Mayhap.” His voice was grave. “We’re wanted at court as soon as you’re ready.”

He knew, as well as I did; Joscelin had been there, when Hyacinthe took on the doom that should have been mine, using the dromonde to trump the offering of my wits and consecrate himself to eternal exile. A fine fate for the Prince of Travellers, condemned to an endless existence on a narrow isle amid the deep waters that divided Terre d’Ange and Alba, bound to serve as heir to the Master of the Straits.

Such had been the nature of his bargain. The Master of the Straits would never be free of his curse until someone took his place. One of us had to stay. I had known it was necessary; I would have done it. And it would have been a worthwhile sacrifice, for had it not been made, the Alban ships would never have crossed the Straits, and Terre d’Ange would have fallen to the conquering army of Skaldi.

I had answered the riddle and my words were true: the Master of the Straits drew his power from the Lost Book of Raziel. But the dromonde looks backward as well as forward, and Hyacinthe’s answer went deeper. He had seen the very genesis of the geis itself, how the angel Rahab had loved a mortal woman who loved him not, and held her captive. How he had gotten a son upon her, and how she had sought to flee him nonetheless, and perished in the effort, along with her beloved. How Rahab had been punished by the One God for his disobedience, and how he had wreaked the vengeance of an angry heart upon his son, who would one day be named Master of the Straits. How Rahab brought up pages of the Lost Book of Raziel, salvaged from the deep. How Rahab gave them to his son, gave him mastery of the waters and bound him there, on a lonely isle of the Three Sisters, condemning him to separate Terre d’Ange and Alba, for so long as Rahab’s own punishment endured.

This was the fate Hyacinthe had inherited.

For ten years and more, I had sought a way to break the curse that bound him there, immersing myself in the study of Yeshuite lore in the hope of finding a key to free him. If a key existed, it could be found in the teachings of those who followed Yeshua ben Yosef, the One God’s acknowledged scion. But if it did, I had not found it.

It was one of the few things at which I had failed utterly.

“Let’s go.” I pushed my plate away, appetite gone. “If something’s happened, I need to know it.”

Joscelin nodded and rose to summon the stable-lad to make ready the carriage. I went to change my attire to something suitable for court, donning a gown of amber silk and pinning the Companion’s Star onto the décolletage, the diamond etched with Elua’s sigil glittered in its radiant gold setting. It is a cumbersome honor, that brooch, but if the Queen had sent for me, I dared not appear without it. Ysandre was particular about the honors she bestowed.

My carriage is well-known in the City of Elua, bearing on its sides the revised arms of Montrève. Here and there along the streets, cheerful salutes and blown kisses were offered, and I suppressed my anxiety to accept such tribute with a smile, for it was no fault of my admirers that my nerves were strung taut that morning. Joscelin bore it with his customary stoicism. It would have been a point of contention between us, once. We have grown a little wiser with the years.

If I have patrons still, they are fewer and more select—thrice a year, no more and no less, do I accept an assignation as Naamah’s Servant. It has proven, after much quarrel and debate, a compromise both of us can tolerate. I cannot help it that Kushiel’s Dart drives me to violent desires; I am an anguissette, and destined to find my greatest pleasure mingled with pain. No more can Joscelin alter the fact that he is made otherwise.

I daresay we both of us know that there are only two people in the world capable of truly dividing us. And one…

No one is ever given to know what might have been.

Hyacinthe.

As for the other…of Melisande Shahrizai, we do not speak, save in terms of the politics of the day. Joscelin knows well, better than any, the hatred I bear for her; as for the rest, it is the curse of my nature and a burden I carry in silence. I offered myself to her, once, at the asking-price of her son’s whereabouts. It was not a price Melisande was willing to pay. I do not think she would have sold that knowledge at any price, for there is no one living who holds it. I know; I have sought it.

It is the other thing I have failed utterly in finding.

It matters less, now; a little less, though there is no surety where Melisande is concerned. Ysandre thought my fears were mislaid, once upon a time, colored by an anguissette’s emotions. That was before she found that Melisande Shahrizai had wed her great-uncle Benedicte de la Courcel, and given birth to a son who stood to inherit Terre d’Ange itself. Now, she listens; now, I have no insight to offer. Though Benedicte is long dead and his conspirator Percy de Somerville with him, Melisande abides in the sanctuary of Asherat-of-the-Sea. Her son Imriel remains missing, and I cannot guess at her moves.

But my Queen Ysandre worries less since giving birth to a daughter eight years ago, and another two years later. Now two heirs stand between Melisande’s boy and the throne, and well guarded each day of their lives; a more pressing concern is the succession of Alba, which proceeds in a matrilineal tradition. Unless he dares break with Cruithne tradition, Drustan mab Necthana’s heir will proceed not from his loins, but from one of his sisters’ wombs. Such are the ways of his people, the Cullach Gorrym, who call themselves Earth’s Eldest Children. Two sisters he has living, Breidaia and Sibeal, and neither wed to one of Elua’s lineage.

Thus stood politics in Terre d’Ange, after ten years of peace, the day I rode to the palace to hear the news from Azzalle.

Azzalle is the northernmost province of the nation, bordering the narrow Strait that divides us from Alba. Once, those waters were nigh impassable, under the command of he whom we named the Master of the Straits. It has changed, since Hyacinthe’s sacrifice and the marriage of Ysandre and Drustan—yet even so, no vessel has succeeded in putting to shore on those isles known as the Three Sisters. The strictures change, but the curse remains, laid down by the disobedient angel Rahab. For so long as his punishment continues, the curse endures.

As the Master of the Straits noted, the One God has a long memory.

I felt a shiver of foreboding as we were admitted into the courtyard of the palace. It might have been hope, if not for the dream. Once before, my fears had been made manifest in dreams, although it took a trained adept of Gentian House to enable me to see them—and they had proved horribly well-grounded that time. This time, I remembered. I had awoken in tears, and I remembered. An old blind woman’s words and a shudder in my soul warned me that a decade of grace was coming to an end.

CHAPTER TWO

Ysandre received us in one of her lesser council chambers, a high-vaulted room dominated by a single table around which were eight upholstered chairs. Three men in the travel-worn livery of House Trevalion sat on either side, and the Queen at its head.

“Phèdre.” Ysandre came around to give me the kiss of greeting as we were ushered into the chamber. “Messire Verreuil.” She smiled as Joscelin saluted her with his Cassiline bow, vambraced arms crossed before him. Ysandre had always been fond of him, all the more so since he had thwarted an assassin’s blade in her defense. “Well met. I thought you would wish to be the first to hear of this oddity.”

“My la…” I caught myself for perhaps the thousandth time; bearing the Companion’s Star entitled me to address the scions of Elua as equals, a thing contrary to my nature and training even after these many years. “Ysandre. Very much so, thank you. There is news from the Straits?”

The three men at the table had stood when the Queen arose, and Ysandre turned to them. “This is Evrilac Duré of Trevalion, and his men-at-arms Guillard and Armand,” she announced. “For the past year, they have maintained my lord Ghislain nó Trevalion’s vigil at the Pointe des Soeurs.”

My knees weakened. “Hyacinthe,” I whispered. The Pointe des Soeurs lay in the northwest of Azzalle in the duchy of Trevalion, closest to those islands D’Angelines have named the Three Sisters; it was there that the Master of the Straits was condemned to hold sway, and Hyacinthe to succeed him.

“We have no news of the Tsingano, Comtesse,” Evrilac Duré said quietly, stepping forward and according me a brief bow. He was a tall man in his early forties, with lines at the corners of his grey eyes such as come from long sea-gazing. “I am sorry. We have all heard much of his sacrifice.”

They would, in Azzalle. It was there that we had come to land, D’Angelines, Cruithne and Dalriada, carried to the mouth of the Rhenus by the mighty, surging wave commanded by the Master of the Straits, the wound of our loss still fresh and aching. And it was Ghislain nó Trevalion who met us there; Ghislain de Somerville, then. He has abjured his father’s name since, and for that I do not blame him.

“Be seated and hear.” Ysandre swept her hand toward the table.

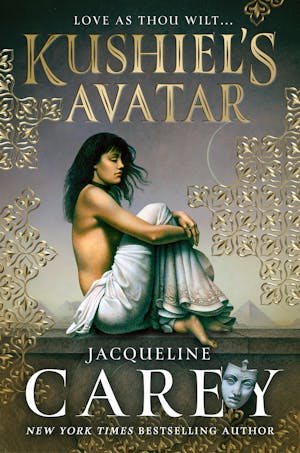

Copyright © 2003 by Jacqueline Carey