[1]Commandos

It only stood to reason that Winston Churchill and the British army’s general staff would be more open to special operators than their American counterparts.

Even before the United Kingdom’s inception as a unified country, much less a global empire, generations of Britishers had shared the prime minister’s reverence for the sceptered isle’s martial heritage. Most did not distinguish these traditions from the UK’s sense of nationhood. Men and women, boys and girls, had reveled in the quests of Welsh Arthurian knights, forest-dwelling Merry Men, kilt-clad freedom fighters, and undercover spies chronicled by scribes from Malory to Kipling to Maugham. It was, after all, the eighteenth-century British general Thomas Gage who, during what came to be known as Pontiac’s Rebellion in North America, had established and trained the country’s first forest-fighting corps of irregulars to crush the Native American uprising.

Moreover, as a twenty-five-year-old war correspondent, Churchill had personally witnessed the havoc that Afrikaner “Kommando” companies had wreaked across the Transvaal during the Second Boer War. Now, four decades later as a second World War raged, these memories played into his famous 1940 instructions to his newly created Special Operations Executive to “set Europe ablaze.” The SOE, an all-volunteer unit, was charged with igniting that fire via sabotage and subversion behind the lines of Hitler’s “Fortress Europe.”

The American officer corps, on the other hand, was far less keen regarding clandestine warfare. Their thinking was reflected in the United States Secretary of War Henry Stimson’s famous quip, “Gentleman do not read each other’s mail.” This chauvinism toward commando forces even led some Stateside generals to dub Churchill’s Special Operations Executive the “Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare.”

As it was, the architects of the American military machine, intuiting Adolf Hitler’s monomaniacal lust for his neighbors’ lands—and foreshadowing Steinbeck’s insight that “All war is a symptom of man’s failure as a thinking animal”—had been quietly placed on a war footing by President Franklin D. Roosevelt long before Pearl Harbor. They now argued that despite the fact that both the British and the Germans had been conducting successful special operations since the outbreak of hostilities across the Atlantic, cloak-and-dagger combat had no upside. In their view, the concept not only failed to contribute to the big-picture war effort, but actually hampered military operations by siphoning manpower and funds from the regular army. In a classic case of fighting the last war, even the War Department’s official history of Special Operations in World War II notes that on the eve of combat in Europe, “American officers … envisioned a future conflict along the lines of the Great War.” That is, a continuation of the huge, blunt-force battles that had originated in America’s War Between the States.

So it was that in the interwar years between the 1918 armistice and the 1941 Japanese strike on Hawaii, superannuated American military theory and subsequent mobilization plans emphasized straightforward conventional tactics. Much of this attitude stemmed from America’s maturity into an industrial behemoth. As the United States flexed its manufacturing might in the twentieth century, the country’s military planners similarly gravitated toward a vision of “big-unit” warfare conducted by large conscript armies slugging it out across the European plains. To American generals preparing to face the German Wehrmacht, that remained the template. The names Ulysses S. Grant and John “Black Jack” Pershing might as well have been verbs, with Grant’s battering-ram campaign against Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia standing out as the valued lesson. The successes of harassing tactics practiced during the Revolutionary War by the likes of Daniel Boone, Francis “Swamp Fox” Marion, George Rogers Clark, and Ethan Allen and his Green Mountain Boys had been reduced to fanciful fables.

This mindset was not altered by the fact that by the time America formally entered World War II, both the Germans and the British had successfully employed special operators to great advantage. It was the elite German Fallschirmjäger paratroopers and glider men who had captured the “impregnable” Belgian fortress of Eben-Emael in May 1940, opening the pathway into France. Conversely, even as Luftwaffe bombs devastated London during the Battle of Britain, the British SOE was arranging for supplies to be air-dropped to partisans in occupied Europe while simultaneously conducting coastal commando raids. One SOE operative dropped behind enemy lines managed to sabotage six Wehrmacht railway engines in eastern France, while another, working with the French resistance known as the Maquis, orchestrated the destruction of a massive Peugeot factory complex now churning out German tanks and planes. Though but military pinpricks, the British found these forays effective at keeping the Germans off balance. The American generals, however, were not impressed.

Given the clashing martial viewpoints between the United States and Great Britain, America’s general staff was mildly annoyed when, in June 1942, the decorated World War I veteran Colonel William Donovan filled the country’s special-operations vacuum by convincing his old Columbia Law School classmate Franklin Roosevelt to let fly an “arrow of penetration” behind enemy lines. Donovan’s enthusiasm for sabotage, subversion, propaganda, and small-unit guerrilla warfare was as palpable as the collection of ribbons and decorations, including the Medal of Honor, he sported upon his return from the Western Front twenty-four years earlier. The scars, and Purple Heart commendations, he carried from his three war wounds only served to solidify his reputation. The result was the establishment of the covert Office of Strategic Services (OSS). Despite the War Department’s pique at what it considered the now-civilian Donovan’s intrusion onto its military turf, the generals and admirals grudgingly recognized that the man nicknamed “Wild Bill” had the president’s ear. To that end, the uniformed brass concluded that if the foreign agents and Ivy League toffs flocking to Donovan’s new OSS planned to swan about Europe playing at cowboys-and-indians, so be it—as long as they stayed out of the way of the true war fighters.* If that meant the army or navy occasionally lending an officer or two to Donovan’s enterprise, such was the small price to pay.

Fortunately for America’s war effort, there was one significant exception to this anti-commando wave of indifference and disdain; one soldier who perceived the value in both Churchill’s and Donovan’s ardor for special operators. He happened to be the United States Army’s chief of staff, General George C. Marshall.

* * *

It was the British vice admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten’s penchant for bold strikes that caught Gen. Marshall’s eye. In October 1941, Mountbatten—King George VI’s nephew and Winston Churchill’s trusted friend—had been appointed to lead Britain’s Combined Operations Services in planning and executing the hit-and-run sorties on the continent that the prime minister so valued. Striking from Norway to Crete, these predominantly nighttime stealth assaults culminated in a commando-led amphibious attack on the strategic German-occupied dry dock of St. Nazaire, on France’s Normandy coast. The success of the raid not only rendered a crucial Kriegsmarine repair station unusable for the remainder of the war but went far to plant the seed in Marshall’s mind for standing up an American quick-strike force with similar capabilities.

As it happened, Gen. Marshall had arrived in Great Britain in early April 1942—one week after the successful St. Nazaire operation—to present Churchill with the American plan for a cross-Channel invasion, code-named Operation Sledgehammer, the following year. While in London Marshall went out of his way to meet with Mountbatten and work out an arrangement for select American soldiers to train at Great Britain’s Commando Headquarters at Fort William in the western Scottish Highlands. That the training depot was tucked away behind a series of rugged hills dominated by the seventeenth-century Achnacarry Castle in the heart of the ancient Clan Cameron country only added to the romance and allure.

Marshall had been planning for an assault on the European continent since 1939, when President Roosevelt had appointed him the U.S. Army’s chief of staff. The former cavalryman had watched closely when, as part of Roosevelt’s New Deal legislation six years earlier, the president had placed the Civilian Conservation Corps under the aegis of the U.S. Department of War. Known informally as Roosevelt’s Tree Army, the CCC’s recruits were supervised by army officers as they cleared forests, fought fires, built roads, and maintained the country’s infrastructure. Though they were not issued weapons, their camps were run with a military efficiency that not only exposed the recruits to the physical challenges of deployments under arduous conditions, but also taught them the more mundane details of military life, ranging from standing at attention to marching in sync. When, at Marshall’s urging, the United States instituted the country’s first peacetime draft in September 1940, many of the three million graduates of the CCC—about 5 percent of the country’s male population—became noncommissioned officers in the regular army.

Across the ensuing months Marshall oversaw a series of military maneuvers in the American South involving hundreds of thousands of these inductees. Their aim was to allow America’s expanding military to test new equipment ranging from rifles to artillery to tanks. By the time the United States entered World War II, Marshall was convinced that the exercises had elevated the U.S. Army into a serious professional fighting force. But Churchill, having already spent several desperate war winters in what Henry David Thoreau called the “harvest of thought,” considered the American cross-Channel invasion plan a potential debacle.

In his meetings with Marshall, it took the prime minister’s most silver-tongued eloquence to convince the American general that his misguided “iron-mongering” would result in disaster. At this point, Churchill argued, Allied forces in general and the Americans in particular remained too ill-prepared and untested to engage in a direct confrontation with the Third Reich’s Wehrmacht.

The hubris of the American high command, Churchill admitted to confidants, was matched only by his own nation’s depleted armories. With Great Britain’s army grievously underequipped, with British factories barely able to turn out planes for the Royal Air Force, and with the Royal Navy shedding capital ships daily to Nazi U-boats, Churchill knew from hard experience what Marshall had yet to comprehend—a landing on the well-defended French seacoast would prove an Allied catastrophe on a scale to make Dunkirk appear inconsequential.

Instead, Churchill proffered an alternative. Why not, he suggested, allow the Soviet Union to weaken Hitler’s armies on the war’s eastern front while Marshall’s raw American troops, with British Tommies by their side, tasted first blood in Axis-controlled North Africa? Victories across the Sahara would not only give U.S. soldiers much-needed combat experience, but also act as a springboard for Allied forces to jump the Mediterranean and invade the Reich’s “soft underbelly” of Fascist Italy.

Marshall was indeed intrigued by the idea of throwing his new divisions against the enervated Vichy forces garrisoning Morocco and Algeria. Once battle-tested against such irresolute opponents, his thinking went, the Americans would be toughened enough to stand toe-to-toe with Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps farther east in Tunisia. It could not hurt, Marshall told confidants, if salted among those armies rolling into North Africa was a cadre of special operators whose British tutors had whetted them to a bayonet’s sharp edge as leaders, teachers, and killers.

[2]Darby’s Recruits

Given his personality and experience, General George Marshall’s concept of America’s new special forces was naturally more buttoned-up than “Wild Bill” Donovan’s notion of a secret strike force composed, as the saying went, of Ivy Leaguers who could win a bar fight. Marshall was well aware that working side by side with Donovan’s college grads were Czarist officers who had fled Russia after the revolution, combat-addled veterans of the Spanish Civil War, would-be adventurers too unmanageable for regular-army strictures, and, in one OSS instructor’s words, “tough little boys from New York and Chicago [anxious] to get over to the old country and start throwing knives.” Marshall, on the other hand, envisioned a more disciplined version of Donovan’s charges—soldiers first, scout-saboteurs second. To that end he tapped the newly promoted Brigadier General Lucian K. Truscott to stand up America’s initial special-operations battalion.

In the forty-seven-year-old Truscott, Marshall had chosen the ideal officer to mold America’s latest iteration of irregulars. The son of a Texas rancher who had once cowpoked along the Chisholm Trail, Truscott possessed what one subordinate described as a “predatory” face whose gap-toothed snarl was complemented by a voice gravelly enough to walk on. A career soldier, Truscott was no stranger to explosive expletives, strong liquor, and tobacco, and in his two and a half decades in uniform he had honed a martial ethos that stressed “speed, vigor, and violence”—the consummate qualities he envisioned in his new charges.

Truscott initiated a series of meetings with Vice Admiral Mountbatten, and during their initial strategy sessions—around the same time that Newsweek magazine informed its readers that the War Department was seeking a name for newly established American units whose duties would correspond to those of British commandos—Truscott received a message from Dwight D. Eisenhower. Eisenhower, then still a major general leading the Planning Division at the War Department, advised Truscott that the term “commando” was already too associated with the British, and suggested he find another name for his special operators. For his part, Truscott was an admirer of the key role the colonial New England frontiersman Robert Rogers had played in what was known in the western hemisphere as the French and Indian War. Truscott settled on Rogers’s coinage for his motley group of backwoods fighters—“Rangers.”*

* * *

Truscott’s next task was culling volunteers from the 34th Infantry Division and the 1st Armored Division, then training in Northern Ireland—some thirty-five thousand American soldiers in all, and the first U.S. combat troops to arrive in Europe since the Great War. Once his Ranger team was assembled, he proposed that they not only train with their British counterparts, but even accompany Mountbatten’s commandos on their surreptitious raids into enemy territory. At the very least, he thought, this would provide the American operatives with a modicum of combat experience. After this temporary deployment attached to British raiders, the Rangers could then return to their former units to impart their experiential knowledge. The concept was remarkably similar to George Washington’s command to the Prussian mercenary Baron Friedrich von Steuben at Valley Forge in 1778—to forge a nucleus of sub-trainers who would then fan out among the regiments of the Continental Army to convey their newfound professionalism. As it happened, the temporary aspect of Truscott’s vision would not quite come to pass.

On June 19, 1942, Truscott officially issued orders activating the 1st Ranger Battalion. Its roster listed zero members. Truscott delegated the job of mustering the outfit’s personnel to the thirty-one-year-old West Point graduate Captain William O. Darby, whom he plucked from the staff of General Russell Hartle, commander of all American forces stationed in Northern Ireland. Darby was charged with building his team from scratch. The enthusiastic, likable, and, most important, indefatigable Capt. Darby proved more than up to the assignment.

Darby established his initial base in the seventh-century Gaelic fortress town of Carrickfergus, on the north end of Lake Belfast, and began circulating flyers among Hartle’s troops calling for volunteers. More than two thousand enlisted men stepped forward while Darby personally interviewed prospective junior officers. Once selected, this new officer corps was tasked with culling and molding a battalion from among the disparate riflemen, tank drivers, and antiaircraft-artillery operators flocking to Carrickfergus. Darby stressed to his staff that he was looking for venturous athletes willing to push beyond their assumed physical limits. He also wanted intelligent soldiers capable of thinking for themselves in an emergency. A few regular-army unit commanders attempted to use the opportunity to rid their outfits of slackers and misfits—“eight balls,” in the vernacular. But Darby’s filtering process proved rigorous, and they were rapidly bounced.

* * *

At the onset of World War II, a conventional United States infantry battalion generally consisted of some 860 enlisted men and 40-odd officers. Darby pictured his stand-alone Ranger unit as a smaller force, perhaps half that size. Within a month he and his subordinates had selected 570 candidates, wisely factoring into his thinking losses from injuries and last-minute defections. By the time their training was complete, 447 enlisted men and 26 officers would form the initial nucleus of the 1st Ranger Battalion. Darby then divided the outfit into a headquarters company and six line companies of 67 men each.

The recruits were, as Darby had hoped, an eclectic cross section of America, hailing from all forty-eight states and ranging in age from eighteen to thirty-five. Though the composition of the unit came nowhere close to the Donovan-esque type of eccentrics drawn to the OSS, the army’s official Ranger history nonetheless reports that the initial roster of the 1st Ranger Battalion ran the gamut from oil rig roustabouts to electrical engineers to bartenders to medical school students and included more than a few former high school and college football stars, a full-blooded Sioux Indian scout, and even a circus lion tamer.

The battalion’s next stop was the British commando school at Fort William. Upon debarking from their troopship, the unit received its first taste of “Rangering” by marching seven miles in full gear to its new garrison in the shadow of the ancient Achnacarry Castle. The grueling trek kicked off three months of day-and-night exercises supervised by British commando instructors. They included what the Americans took to calling “Limey Humps”—quick-step marches through freezing rivers and up and over the region’s mountainous terrain. These footslogs bookended training in hand-to-hand combat and tank-ambush tactics, booby-trap and demolition courses, and navigation of small lake boats. During one early war game an American enlisted man saluted a major in the Royal Marines. His reward was a swagger stick to the solar plexus and a verbal dressing-down. On a real battlefield, he was told, he would have just made the officer a prime sniper’s target.

Following British commando custom, the exercises stressed realism. This meant crawling through obstacle courses beneath spitting machine gun slugs and disposing of live hand grenades casually tossed by British subalterns into the midst of the Yank apprentices. Every evening, at the shrill blast of an instructor’s whistle, the Rangers would dash to the nearest “felled forest” for the dreaded log-lifting drills. The exercise consisted of six men hefting a heavy tree trunk between ten and fourteen feet long to one shoulder and, on command, shifting the burden to their other shoulder in unison. As time went on the orders to shift shoulders became more rapid, resulting in the heads of the weary soldiers being rapped incessantly. Even less appreciated were the unnerving “death slides,” in which a Ranger would climb a forty-foot tree and, as live fire rent the air about him, slide down a single rope suspended over a raging river. Every Ranger was required to participate.

From time immemorial, professional-army boot camps had been intentionally structured not only to instill in trainees the practicalities of war fighting, but to be as difficult and draining as possible in order that the shared suffering and stresses would forge a strong esprit de corps. Because men washed out of Darby’s battalion daily, the captain made frequent trips back to Northern Ireland in search of replacements. As Darby hoped, the recruits who did manage to survive soon fell into a training groove that so stiffened morale that, in their rare down times, the Rangers practiced applying green and black camouflage paint to each other’s faces and teaching new arrivals how to break down and operate enemy small arms.

* * *

In early August the 1st Ranger Battalion packed its gear and bade farewell to Achnacarry Castle. Its next assignment was a forty-five-mile, full-gear march south through the crofted landscape to the Royal Navy training center at Argyll. There the Americans—having picked up the sobriquet “Darby’s Rangers”—were drilled in amphibious landings before crossing the Highlands to Dundee, on Scotland’s east coast, to rehearse the techniques and tactics of attacking pillboxes. It was at Dundee that, at the insistence of President Roosevelt, fifty of Darby’s troopers—six officers and forty-four enlisted men—were selected to accompany British and Canadian commando battalions spearheading the 2nd Canadian Division’s amphibious assault on the German-held port city of Dieppe in northern France. This was the American Rangers’ baptism of fire, and it proved a disaster for the Allies.

Unlike the raid on St. Nazaire, the August 19 attack on Dieppe was conducted in daylight. Lacking sufficient air cover as well as the element of surprise, thirty-three of the Royal Navy’s landing craft as well as a destroyer were sunk by German torpedo boats while Wehrmacht machine gunners and mortarmen positioned on the chalk cliffs to either side of Dieppe’s harbor decimated the Canadians who made it to shore. The rout was so thorough that Marshal Philippe Pétain, leader of the Vichy French government, forwarded congratulations to the German High Command.

Churchill and Mountbatten attempted to put the best face they could on the fiasco, citing lessons learned that would be applied to a grander cross-Channel invasion—primarily the need for coordinated naval gunfire and bomber support, better obstacle-removal and beach-control assignments, and even the utility of adapting tanks for amphibious landings. Similarly, in his own after-action report, Capt. Darby—who had been rebuffed when he volunteered to lead the Ranger contingent on the cross-Channel mission—emphasized that his troopers had fought with valor.

To an extent the whitewash worked. American newspapers trumpeted the deeds of the first U.S. soldiers into European combat, with The New York Times leading the boosterism. The paper of record rejoiced that “for the first time United States troops took part in a raid on the continent.” Disingenuously if hilariously ignoring the tiny role the Rangers had played, the newspaper added that “the raiding force also included Canadians, British, and fighting French.” Despite the gloss, however, of the more than six thousand Allied troops who had taken part in the landings on Dieppe’s flint-stone beaches, over half had been killed, wounded, or taken prisoner—including three Rangers killed in action, eleven wounded in action, and four missing and presumed captured.

No one was more aware of the truth of the operation’s appalling failings than Gen. Truscott, who had observed the action from an offshore ship. As War Department publicists basked in the positive news coverage, Truscott was left with a counterintuitive takeaway from the mission. In an effort to follow the template of returning the Rangers to their original units after a taste of combat, Darby’s troopers had been dispersed haphazardly among the British and Canadian commando teams—four here, twelve there; in a few cases even in ones and twos. Tagalongs, at best. Now it dawned on Truscott that perhaps the special operators might work and fight better as a single, cohesive unit.

Truscott did not know it, but his thinking was mirrored by Gen. Marshall. Post-Dieppe, Marshall began to reconsider his original idea for the deployments of America’s Ranger force. For as it happened, the U.S. Army’s highest-ranking officer now needed Darby’s small and mobile outfit elsewhere.

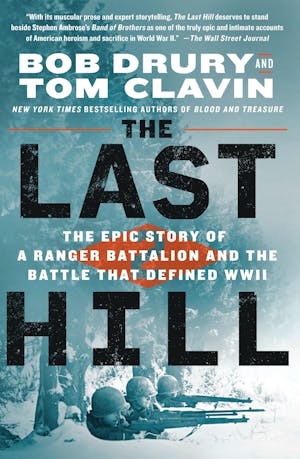

Copyright © 2022 by Bob Drury and Tom Clavin