1

“This is no work for a soldier,” said Saint-Réjant. “I joined the army to get out of farming.”

“Did you gripe this much in the army?” Carbon asked.

“Only until they made me a general.”

“You’d enjoy the work better if you’d served aboard ship. Once you’ve survived battle with the enemy, the sea offers you a second chance to die.”

“It wouldn’t make me any more wet.”

The rain had begun at dusk and settled into a monotonous drizzle, icy and glutinous. It dripped off their slouch brims, their noses too, and the ropy mud of the boulevard clung to their boots and made them heavy as sledges. It turned a level stretch into an uphill climb.

The date was 24 December, 1800 (4 Nivose, Year VIII by the Revolutionary calendar). Traffic was heavy, despite the weather. France had cut the heads off priests and abolished religion, but after a dozen years of austerity, Parisians insisted on celebrating Christmas Eve. Twice now, Carbon had almost been run down by carriages bearing drunken revelers toward the Rue Saint-Nicaise. After the second near miss he’d cajoled Saint-Réjant and Limoëlan to step down from the cart and help him lead the lame, wind-broken mare.

Carbon, a naval veteran, and one admittedly inclined toward recklessness for the sheer thrill of it, nevertheless considered his companions bad risks. Saint-Réjant, most recently a common bandit, had found that occupation more to his liking than his late service to the King, at the expense of his commitment to the Cause, and Limoëlan’s lust for vengeance was the very thing that had led the despised regicides to ruination. If this plan had a flaw, it was his partners.

“Shit!” Limoëlan stepped in a hole, turning his ankle and slamming him shoulder-first against the cart. It lurched. Something heavy shifted under the sodden pile of hay.

Carbon snatched his arm. “Watch your step, ass! You want to blow us all to ashes?”

* * *

A week earlier, on 17 Frimaire (December 17 to the rest of Europe), a grain dealer named Lambel had admitted to his shop in the Rue Meslée a thickset man with a blond beard and a large scar above his left eye. He walked with a rolling gait that spoke of years at sea.

The man paused, breathing in the sweet smell of oats and wheat preserved in barrels; an odor the merchant himself no longer noticed. “Will you hear a proposition?”

“That would depend on the proposition,” said Lambel.

“I sell textiles. I recently came into possession of a shipment of brown sugar, which I hope to barter for bolts of cloth in Brittany.”

“You’ll have no problem selling that lot in Paris. The women in the Tuileries would scratch out each other’s eyes for three yards of muslin. For silk they would do murder. I don’t exaggerate.”

“At the moment I have no way of transporting either the sugar or the cloth. I understand you have a horse and cart for sale.”

“I have for a fact.”

“Will you take two hundred francs?”

“I would.”

Lambel was under no illusion that the man was trading in either cloth or sugar: He had been too quick to offer the money without inspecting the horse and cart. More likely his cargo was English Port, or some other product outlawed by government embargo. But the times were too uncertain to quibble over a fellow’s motives, and Marguerite, the mare, was very old and had a cataract. He helped the man with the scar hitch her up and watched him lead her out of the barn behind his place of business.

* * *

The man with the scar stopped at a wine shop, where he bought a spare Macon cask large enough to contain sixty gallons. Once again the customer explained that he intended to transport sugar. The proprietor helped him load the cask aboard the cart. From there he went to a shed he’d rented in the Rue Paradis near Saint-Lazare. He drew the doors shut, but they were joined poorly, and neighbors had a largely unobstructed view of what went on inside.

One did not trespass, of course. Was a curious fellow resident no better than a voyeur? But there were few enough entertainments at the best of times, and most of them taxed by the Republic; a free show was not a subject for question.

The spectacle taking place across the narrow street was not without curiosity. When two more men appeared and set to work reinforcing the cask with ten stout iron bands, conversing in whispers all the while, it was assumed they were brandy smugglers, hardly an unusual sight that time of year, when a dram was just the thing to drive the cold from one’s bones, even at black market prices.

The neighbors paid them little attention after that. The mystery was explained, and as for reporting the activity, there was no telling what miseries may follow any kind of contact with the authorities, however civic-minded. Madame Guillotine seldom distinguished between accuser and accused.

* * *

François Carbon was neither a cloth merchant nor a brandy smuggler, but a Brittany-born sailor who came by his fearsome scar when a line broke loose during a storm in the Channel and the frayed end struck him above the eye, gouging out flesh like a piece of grapeshot. He had no sugar in his possession. He’d trained in the proper use of firearms and explosives under Georges Cadoudal, a French Royalist who operated a camp for insurgent expatriates in England, on the estate of a British peer in sympathy with the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy in France. (Where, after all, might it end? George III in exile or executed, and the American parvenu Thomas Jefferson in charge of the Empire? As well a bishop!) Although still in his thirties, Carbon had seen the government of his adopted country change hands three times.

He was determined to make it four.

The two men seen working with him on the cask were Pierre Robinault de Saint-Réjant and a master cooper named Jardin, who’d been recruited to forge and fashion the iron bands. Jardin thought the cask stout enough for its purpose, the storage of wine; but a job was a job, and the man with the scar paid up front and in cash, not in promises or poultry. Saint-Réjant wore his civilian attire with the air of a uniform, snug and tidy and with nothing dangling loose, his handkerchief tucked inside his sleeve. He’d served as a divisional general under Cadoudal, and knew little of casks and cart horses.

A fourth man who visited the shed from time to time was later identified as Joseph Pierre de Limoëlan, an aristocrat who’d seen his father borne, fettered and beaten, past jeering crowds to the Place de la Revolution to have his head taken from his shoulders. Cadoudal, a conservative commander not given toward impulsive promotions, had made Limoëlan a major general after he returned from patrol swinging the head of a Jacobin leader by the hair. Individual initiative must be rewarded.

When the cooper left, Limoëlan stood watch at the door while Carbon and Saint-Réjant drew the sacking off two kegs and poured black powder into the cask, then scooped broken and jagged pieces of stone from a barrow and mixed them with the powder; “to slash flesh and pulverize bone,” explained Limoëlan, who’d suggested the refinement, “and make as many good revolutionaries as possible.”

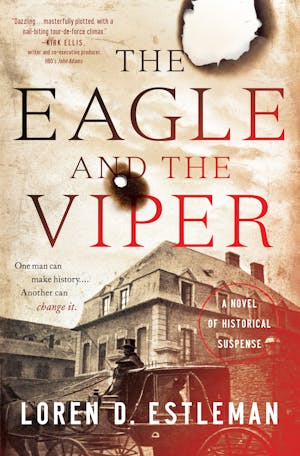

Copyright © 2021 by Loren D. Estleman