INTRODUCTION

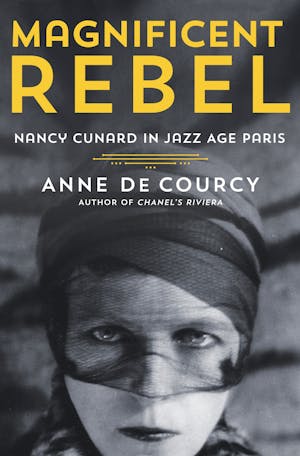

Whatever one thought of Nancy Cunard, it was impossible to ignore her – her beauty alone would have seen to that. Although in photographs she is usually seen with unflatteringly pursed lips, her looks were something commented on by everyone who met her, with her huge blue-green eyes, emphasised by their circles of kohl, invariably remarked upon.

Her personality was equally extraordinary. Around her shimmered a force field of energy that drew people in, often influencing them in ways they could hardly have credited before they had met her. Osbert Sitwell talked of her ‘ineffable charm and distinction of mind’; Alannah Harper thought that ‘whatever she did – however violent – Nancy always looked more distinguished than other people’. Harold Acton believed that she had inspired half the poets and novelists of the Twenties.

What was not always obvious was that much of her extraordinary energy drew its power from an underlying anger – sometimes explosive on behalf of a cause, or a righting of what she saw as an injustice, sometimes a slow-burning resentment that simmered below the surface, as in her relationship with her mother. Later, it would power her campaigning against injustices, especially those perpetrated against black people, fights which she pursued with immense courage and complete scorn for what anyone else thought.

This hostility to her mother, to her mother’s attitudes, friends and social life – Emerald Cunard was perhaps the greatest hostess of the inter-war years – gradually built up during Nancy’s adolescence. Born into a life of wealth and privilege, yet one in which she hardly saw her parents, her childhood was lonely and constrained by a stern and unpleasant governess. Highly intelligent and a poet from early on, she rebelled against what was expected of her and her contemporaries – a debut, followed by a London Season or two, marriage to some suitable young man, children and the running of a large house, probably in the country. What she wanted instead was a life in the arts, with the constant company of artists, writers, poets and painters, found in the great Soho cafés rather than the ballrooms of Mayfair.

Escaping from her mother’s influence through an early marriage, quickly followed by its disintegration, she soon made what was arguably the most formative decision of her life – she would live not in England, but in Paris.

She arrived there at the beginning of 1920, to stay for approximately fourteen years, the period I cover in this book. Here was everything she wanted: the richest and most stimulating artistic life in the Western world, untrammelled sex and plenty of alcohol (the last two quickly became addictions). In addition, it was close enough for her to keep in touch with her English friends, including, and especially, George Moore, her mother’s lover and the man Nancy herself had loved since early childhood. (They would remain close until Moore’s death just before she left Paris.) Moore, then a major literary figure, had taken a great interest in the lonely little girl, talked to her as an equal, encouraged her writing, reviewed her poetry and kept in constant and loving touch, often coming to Paris to visit her.

It was in Paris that Nancy became a cultural icon, a muse to Wyndham Lewis, Aldous Huxley, Tristan Tzara, Ezra Pound and Louis Aragon. Mina Loy wrote poems to her; Constantin Brâncuși sculpted her; Man Ray photographed her; she played tennis with Ernest Hemingway, and after meeting her the poet William Carlos Williams kept her photograph on his desk at all times.

A poet herself, she set up a publishing house called the Hours Press, and published the poems of others (Nancy was the first person to publish work by Samuel Beckett). It was during these Paris years, too, that what to my mind were Nancy’s five most important love affairs took place – affairs that are just as much a portrait of Paris as it was then as of romances, sweeping her into circles and ideas that she might otherwise not have met.

Everyone has their own definition of ‘important’, but in these pages I am taking it to mean the loves that had either the most impact on Nancy or on the literature and life of the time. The first of these, which throughout most of her first year in Paris did much to sear the city’s romance and glamour into her mind, was with the Armenian writer Michael Arlen. Vividly accurate descriptions of Nancy are threaded throughout his stories; and it was the picture of Nancy as heroine of The Green Hat that shot him to global best-sellerdom and for which she is often remembered.

After they had parted – somewhat acrimoniously – came Ezra Pound. Nancy had met him when she was sixteen, by which time he had already made a name in English literary circles, but they did not become close until her Paris years. She admired Pound enormously, not only for his somewhat theatrical good looks and deep classical learning but for the way in which he tirelessly promoted the work of writers in whom he believed, and also for his ability to discover new talent – to one friend who ran a small magazine he sent off the early work of three future Nobel Prize in Literature winners, Yeats, Rabindranath Tagore and T.S. Eliot.

The married Pound, a tireless pursuer of women, was perhaps the only man whose feeling for Nancy was less powerful than hers for him, so much so that she remained in his thrall for several years, only finally giving up after she heard his wife had become pregnant – wives were, to Nancy, if not exactly an irrelevance, certainly no barrier to a liaison.

The third of the five affairs that to me seems noteworthy was with Aldous Huxley, author of Brave New World and nominated nine times for the Nobel Prize in Literature, who became so obsessed with her that he was unable to work and was forced to flee the country in order to continue writing – there are vivid echoes of Nancy and his hopeless passion for her in several of his books.

When she met Louis Aragon, the handsome, brilliant poet and writer who was co-founder of the Surrealist movement before becoming the leading intellectual of the Communist Party, the two fell passionately in love. His influence on her was strong: through this (fourth) affair she became ever more left-leaning. Yet although she could never have been described as a champagne socialist, she saw no contradiction in fervently advocating communist principles while leading a life only possible because of a large income that came from inherited money.

For two years the couple were blissfully happy, until Nancy’s self-destructive streak asserted itself. Not for the first time, while attached to one man she began an affair with another. Much of Aragon’s best poetry about her was written after their break-up.

This was caused by Henry Crowder, a black jazz pianist whom she had met while in Venice with Aragon and who was the unwitting catalyst for her eventual irrevocable breach with her mother. For Nancy, this was the most formative – as well as the longest – of her many relationships. It was Crowder, himself a peaceable man, who inspired her in her battle with the many injustices suffered by his race, culminating in her major work, Negro, an anthology of writings by and about black people. As she said later, ‘Henry made me.’ With their eventual parting came the end of her Paris life.

CHAPTER 1. The Friendship

No two people could have been less suited to each other than Nancy Cunard’s parents. Sir Bache Cunard (the grandson of the founder of the Cunard shipping line) was a fox-hunting squire interested only in outdoor sports and, unusually, silversmithing and wrought ironwork; Maud Alice Burke, Nancy’s mother, a blonde and pretty San Francisco heiress almost twenty years younger than her husband, was intelligent, witty and cultured and seldom set foot out of doors (the story goes that when he built her a rose garden to tempt her out she only entered it once). Maud had, in her usual headstrong fashion, married her much older husband partly because his English title made him seem a highly suitable parti, but largely to avoid the appearance of being jilted – the Polish prince at whom she had set her cap had publicly stated that they were not engaged, and indeed had gone on to marry another rich American girl.

Nevill Holt, the large country house in Leicestershire to which Sir Bache brought his bride, is situated on a slight rise that gives it a view clear across the Welland valley. Built of grey and yellow stone with a turreted façade, at its centre is a high, timbered late-fourteenth-century hall. At one end is a small thirteenth-century church, with a modest graveyard behind it, the headstones aslant with age, to which Nancy often retreated as a child. The large Victorian dining room overlooks lawns and the red-brick walls of the kitchen garden. Inside, the Cunards had introduced dark Jacobean wood panelling. Outside, some of Sir Bache’s wrought ironwork still remains – waves and anchors symbolising the origins of the Cunard fortune, in Sir Bache’s case sadly depleted.

When the couple married (in 1895), Maud’s money enabled her to begin work on the large, isolated house in which she found herself – house decoration was always one of her passions – repainting walls and woodwork, adding oriental rugs and silk curtains and assembling various suitably medieval effects, from suits of armour to tapestries. While Maud rearranged the drawing-room furniture, Sir Bache worked in his room in the house’s sixteenth-century tower, where he made silver leaves to decorate the dining-room table and turned half-coconuts into silver-mounted cups.

Although often depicted merely as a featherbrained socialite thanks to her later career as a leading hostess, Maud was anything but. She had a deep love of music and literature; Osbert Sitwell, who knew her well, claimed that she had read many Latin and Greek writers as well as the whole of Shakespeare and Balzac. In the evenings she would play Chopin and Beethoven and read the classics and French literature late into the night, tastes which must have influenced her daughter.

Their only child, Nancy Clara Cunard, was born on 10 March 1896, to a childhood that was then typical for the upper class – numerous servants, fresh flowers in her room every morning and absentee parents. Often she did not see either of them for months at a time, a loneliness-inducing practice that affected girls more than boys, as the latter almost always went off to school at around thirteen. More stultifying still must have been the lack of physical contact – the cuddles, kisses and hand-holding that are so necessary for small children and part of normal child-parent relationships. Brothers and sisters would have helped mitigate this but Nancy was an only child, Maud having felt that with her daughter’s birth she had done her duty and could carry on with her own life.

Although Nancy was too young to recognise such feelings, she was desperately lonely and craved affection. She longed for her mother’s presence and was happy to be dressed up and shown off by her, sometimes in black velvet that set off her golden hair, sometimes in simple cotton. All her life Nancy was to have a love of beautiful clothes with an original twist to them – her later diaries invariably mention new outfits and how pleased she is with them. This showing-off would happen during Maud’s house parties, unusual and stimulating groups of people that, instead of merely the usual run of aristocratic couples, included anyone from the Prime Minister, H.H. Asquith, and his wife Margot to musicians, poets, artists and writers.

One of these was the man who became Nancy’s lifelong friend, the Irish novelist George Moore, who was her mother’s lover and who some thought might have been Nancy’s genetic father. It was a rumour fairly widespread at the time, probably fuelled by the obvious interest he took in this engaging child; but there is no evidence to support it and today it is largely discounted. Nor, except for the fact that both were fair rather than dark, did she resemble him at all physically, as she herself noted later on. Moore was always known by Nancy as GM.

* * *

Moore and Maud Burke (as Lady Cunard then was) had first met at a banquet at the Savoy. Maud, who admired Moore greatly for his defence of Emile Zola,1 was so determined to meet him that she had slipped in earlier and changed the place cards so that she could sit next him. Looking extremely pretty in a grey and pink shot-silk dress, she sat beside him drinking in every word. When he paused for breath, she placed her small hand on his arm, turned her ardent blue gaze on him and said passionately, ‘George Moore, you have a soul of fire!’

For Moore it was a coup de foudre and she remained the love of his life. Twelve years after that first meeting he wrote to her, ‘I am the most fortunate of men; surely the most fortunate man in the world is he who meets a woman who enchants him as a work of art enchants … if I have failed to write what I dreamed I might write, one thing I have not failed in – you. You are at once the vase and the wine in the vase … A sky full of stars does not astonish me more than your face, your marmoreal eyes … you can never form an idea of the wonder it is to me to see you – to think you and dream you.’ Much later he evoked her ‘brightly coloured cheeks and fair hair, fair as the hair in an eighteenth- century pastel … very few men have seen their ideal as close to them and as clearly as I have seen mine.’

George Moore was born in February 1852, the eldest son of George Henry Moore, of Moore Park, a nationalist Irish politician who was also a Westminster MP and who died in 1870, leaving the eighteen-year-old GM a rich man. Once independent at twenty-one, Moore handed the management of the estate to his brother Maurice and left for Paris to study art, which he had always wanted to do, in large part because of the opportunities it offered of legitimately gazing at naked women (by his own admission he spent hours daydreaming of undressing women), since most Parisian models happily posed nude. In Paris he lived, like many art students, in the Latin Quarter – although, unlike them, he stayed in a smart hotel and kept his own valet – until, having published a book of poems at his own expense, he decided instead to become a writer.

When he published Esther Waters (his seventeenth book) in 1894 it became an instant best-seller, receiving rave reviews everywhere (earlier books had been banned from the powerful circulating libraries because their themes had been considered too immoral). Set in England from the early 1870s onwards, the novel is about a young, pious woman from a poor family who, while working as a kitchen maid, is seduced by another employee, becomes pregnant, is deserted by her lover, and against all odds decides to raise her child as a single mother – then, she would have been thought of as a ‘fallen woman’. Even the former Prime Minister Gladstone, whose favourite hobby – along with chopping down trees – was saving such females, praised the book in a letter to the influential Liberal newspaper the Westminster Gazette. It brought Moore both kudos and financial security.

Nancy described GM as her ‘first friend’. As her mother’s long-time lover and adorer, he came often to Nevill Holt. Here he took a close interest in Nancy, spent time with her, never talked down to her and indeed became the central figure of her childhood. She first remembered him when she was four and he was forty-eight and famous.

* * *

The first thing Nancy noticed about GM was that he spoke differently from the rest of her parents’ friends: his rich voice was tinged with an Irish brogue, and while he talked he gesticulated constantly with his plump white hands with their tapering fingers. He had champagne-bottle shoulders, the red hair of his youth had faded to a golden-white, his face was pink and white and his eyes pale blue; he moved so softly that Nancy often thought there was something cat-like about him.

He was known as a good conversationalist, if rather too uninhibited for the era. Harold Acton, the son of an Anglo–Italian baronet who as a youthful aesthete2 had become a member of Maud’s circle, described how, when the rest of the party went off to play bridge, he would join Moore, who was invariably outspoken about the other guests, even when they were within earshot: ‘his directness and the round steadiness of his gaze fell like an icy shower on prevailing conventions. Nothing appeared to embarrass him … he would tell of his troubles with an enlarged prostate, describing them with clinical detail. Egoism in him had become a shining virtue.’ He once left a grand house party3 without warning, leaving only a note for his hostess that said, ‘I am sorry to leave without seeing you, but I can no longer stand the love-making of the doves by my window.’

GM was witty, he was amusing and he loved gossip. At Nevill Holt he had a licence to be the enfant terrible. When he was offered salt, Nancy heard him say, ‘I thank you, no I do not wish for any of that salt. Oh, of course, if you insist, go ahead. But you will be eating the bones of your ancestors.’ To him, salt should be sea salt, not the sort ‘refined with detestable chemicals and powdered bones for whiteness’.

If people found some of his conversation too near the bone, Maud would tell her guests that not only was GM the life and soul of the party but he should not be taken too seriously – many of his remarks were exaggerations, to provoke a reaction. Some of Maud’s country neighbours did not know what to make of his frequent frankness about things that – then – were thought better left unsaid. While watching a field of lively young bullocks, some of which were attempting to mount each other, GM, instead of politely ignoring them, remarked, ‘Poor bullock, poor bullock – he would like to but he can’t.’ He would also rail against prudery: fig leaves, it seemed, were coming in again, and in Rome the finest statues of antiquity … oh, it didn’t bear thinking about.

One of the guests who enjoyed these occasions was the young writer Osbert Sitwell. ‘Very often, [George Moore] was out to shock; and when he had said something that he hoped would appal everyone in the house or even in the garden, a seraphic smile would come over his face, and remain on it, imparting to it a kind of illumination of virtue, like that of a saint, for several minutes; the bland unselfconscious smile of a small boy.’

But Maud did not hesitate to berate GM if she thought he had gone too far. Coming from Ireland, where Catholicism was so entrenched it sometimes verged on superstition, GM talked frequently about what he called ‘papistry’ – mocking not sincere religious faith but dogma, the inordinate ascendency of the priests in Ireland, the threat of hellfire. Suddenly he would interject a flippancy – what would they do about Holy Communion if Prohibition came in?

‘Really GM,’ said Maud crossly one day, ‘Can’t you be more tactful? Miss X is the daughter of one of the great Catholic families of England, and you know it. And yet you go walking with her and upset her thoroughly with your nonsense … she went straight to her room when you came in from walking and hasn’t been seen since.’ For several days GM was uncharacteristically silent and in disgrace.

Maud was also angry if he was late for meals: in a house with a large staff of servants, punctuality was essential if everything was to run like clockwork.

‘Go and tell Mr Moore we can’t wait any longer,’ Maud would say to a footman about to serve lunch. ‘Where is he?’

‘Mr Moore is still writing in the Long Room, your Ladyship.’

‘Go and tell him to come down at once!’

After some time, the footman would return, red-faced and out of breath, to face an angry Maud, a temperamental butler and hungry guests.

‘What have you been doing for so long, William?’

In confusion the poor footman would answer, ‘Mr Moore wanted to ask me everything I thought about cricket, your Ladyship.’

Well after lunch had been started GM would appear, realise he really was late, excuse himself volubly and explain how he had become interested in the footman’s views on cricket.

Sometimes GM would walk around the garden with Nancy, looking at the rooks and jackdaws or starlings; sometimes they would go further afield. She remembered one walk in particular, to Holt Wood, on a July day when most of the wildflowers were gone.

‘Flowers, like us, Nancy, have their season,’ said GM. ‘But that is the yaffle’s cry! I am not mistaken. He is with us the whole year round.’ ‘Yaffle’ he told the ten-year-old Nancy, was a much nicer word than ‘woodpecker’.

As a small child, Nancy longed to read. She could manage small words like ‘cat’ and ‘dog’ but longer ones, and phrases, were too much for her. The lonely, precocious little girl would question GM vigorously about anything that interested her and he would do his best to answer. Once, when she was five, she took GM to the little churchyard behind the Holt chapel, where they sat on one of the beautiful old gravestones. ‘I often come here alone,’ she said. ‘And I often wonder where we go after we are dead.’

* * *

When Nancy was nine, her life was taken over by an appallingly strict governess, whose reign instilled her with a powerful, lifelong dislike of authority. Miss Scarth, who had arrived with excellent references, was indeed a good teacher – albeit one who reinforced her methods with a steel ruler. Nancy’s daily regime now began with a cold bath, in winter and summer, followed by porridge and a heavy English breakfast that she found hard to swallow – one of Miss Scarth’s diktats was that Nancy had to finish every scrap of food on her plate, and the small child would often sit for hours before she could bring herself to swallow the slowly congealing mess that remained, a treatment that left her with a lasting distaste for food, which she would always associate with punishment.

It was, of course, the custom for the children of upper-class families to be handed over to nurses and governesses almost from birth, but even by the standards of the day Maud’s neglect of her daughter was virtually total – her social life and its demands took up all her time. Once Miss Scarth had been engaged, Maud felt she had done everything necessary for her child. Nancy’s complaints about her treatment by her governess were disregarded while Maud continued her own life unhindered, an abandonment that must have gone much of the way to fuelling Nancy’s later resentment of her mother. Her father, a vague, distant but affectionate presence, left the upbringing of his daughter to his wife, as was then customary. It was during these years that Nancy’s affection for GM, the only person who took a real interest in her, became so firmly grounded.

Copyright © 2022 by Anne de Courcy