1

The blood never much bothered Grace. Maw Maw Rubelle got her used to it early on, when she was little ol’, way before she let her only granddaughter, her apprentice, tend the stove at her first baby catching—before, even, Grace’s first blood trickled down her thigh. There it was, her monthly making a dark red liquid trail past her calf and ankle, dripping into the thick, fertile Virginia dirt she’d planted her feet in as she reached for the pins on the laundry line. Grace cocked her head and stared at it in wonder for just a moment, then went on in the outhouse and made her sanitary pad, just like Maw Maw Rubelle had taught her to do with the pins and ripped pieces of feed sack. Just as natural and nasty as slopping hogs, Grace thought.

Now her best friend, Cheryl, she didn’t see it that way. She cried holy hell when her blood came in. Nobody—not her mama, not her big sissy, not nan auntie—bothered to tell her what was inevitable. They held it to their chests like a big secret Cheryl had no right to know. She near killed her fool self when she saw the red puddle on her little piece of school bench and realized it was oozing from her poom-poom—knocked over the desk, tripped down the rickety schoolhouse steps, and just took off running down toward Harley pasture, hollering and screaming like a stuck pig, the laughter of the boys and the screams of Ms. Garvey, their school teacher, chasing behind her.

But Grace, she understood the power of the blood. Maw Maw Rubelle saw to that—made her look straight at it for sport and for practicality’s sake. Maw Maw knew, after all, that her grandbaby would have the calling—saw it in a vision just as plain as day one afternoon as she pulled poke sallet roots from the ground deep in the woods down by the river, where she had gone to forage and be still and make offerings to the spirits of her mother and her mother before that. In the vision, there’d been Grace’s hands—small, delicate, strong—gently twisting, pulling a baby’s head as it emerged between its mother’s legs. The movements, the way Grace’s fingers fluttered about the infant’s curls, had made Maw Maw’s heart beat fast. She could feel her granddaughter’s happy in the tingle of her own fingertips, in each of her own palms. Maw Maw had slowly fallen to her knees, sticks and pebbles digging into the thick of her skirt; she’d kissed those palms, and pressed them—warm, pulsing with energy—to her cheeks. Love was there. Grace would continue in the tradition of the Adams women. Maw Maw’s dead did not lie. Show her the blood, they’d whispered in the breeze, in the beams of light rushing through the leaves. Show her what she already knows.

Maw Maw had pulled a hand towel from her bosom, wrapped the root, leaves, and berries from the small weed stalk in it, and, with a heave, leaned all her weight against her walking stick as she struggled to stand. As quick as her thick legs could take her, she’d hobbled through the brush, across dirt and grass, past the great pear tree and the bumbleberry bush, back to the clapboard shotgun house she’d called home since she was a little girl being taught the ways of a midwife by her own grandmother.

Maw Maw pushed through the back door, squint-searching the tiny, two-room house, her eyes traveling from the bed and small bureau to the kitchen table and three wooden stools Mr. Aaron had fashioned from a fallen oak tree in exchange for two months’ worth of Maw Maw’s Sunday dinner plates, past the fat-bellied wood-burning stove and huge iron kettle standing sentry atop it, over to the corner beneath the window she’d opened to let the breeze carry in the scent of the gardenia bush planted on the side of the house. There was Grace, splayed like one of the little rag dolls her mama had sewn for her last Christmas, stitching baby clothes Maw Maw had commissioned her to make for a client due to have a baby any day now.

“Come here, baby,” Maw Maw had said as she placed the pregnant dish towel on the kitchen sideboard. She’d carefully unfolded it and separated the leaves from the roots from the berries as Grace scrambled to her feet. “Bring Maw Maw Ruby her bag.”

Grace, then eight years old and therefore eager, had practically flown to the chest where Maw Maw kept her special bag. Somebody was having a baby and Maw Maw had to hop to, Grace knew, because that’s what her grandmother did—she waited on babies and when they came, somebody would call on Maw Maw and she would get her bag and her walking shoes and play with the baby until the mama was ready to play with the baby herself. Or something like that.

“Who baby coming today, Maw Maw?” Grace had asked excitedly as she struggled to gently place the weighty black bag on the table next to her grandmother.

“Nobody, chile,” Maw Maw had said. The chair she dropped into creaked as she settled herself onto its frame. She’d torn off a small piece of a newspaper she had tucked in the bag and gently placed a few berries in it before stashing it in a small pocket she’d sewn in the seam of the leather tote. She’d planned to run them by Belinda’s place on the way to the icehouse the coming Saturday, as the young mother-to-be was due sometime in the next couple weeks, and a woman with a stomach stretching out as far and wide as she was practically tall needed a little pick-me-up to remind her that she was still a lady, worthy of affection. Worthy of touch. Pretty. A smudge of those berries across her lips would have Belinda remembering her fine—Belinda and her man, who Maw Maw had heard was down there at The Quarters, drinking and smoking and grinding and forgetting he had a beautiful pregnant wife back home. “Come here, baby,” Maw Maw had said, signaling to Grace. “Stand right here.”

Grace inched between Maw Maw’s knees and melted her face into her grandmother’s fingers.

“One of these days, this here bag and everything in it gon’ be yourn,” Maw Maw had said, looking into Grace’s piercing brown eyes. She let her thumb rest in the one dimple Grace had, a subtle dent in her right cheek.

“You mean like in my picture show, Maw Maw?” Grace had asked.

Maw Maw pulled her face back from Grace’s and wrinkled her brow. Always, Grace woke up next to her grandmother, snuggled up under her arm, and recounted her dreams—she called them “picture shows” on account she imagined that’s what it would be like to watch a film in a theater, something she hadn’t yet had the pleasure, money, or right skin color to do—before the two of them put their feet on the floor, fell to their knees, said their morning prayers, and set out water and bread for their dead. Maw Maw always listened intently, as she knew the power of dreams—understood they were not at all dreams but a nod of things to come. Messages. Sometimes warnings. Surely, Maw Maw had thought, she would have remembered Grace telling her about a dream that involved her midwifery bag. “What dream you had, chile, you ain’t tell me ’bout?”

“I was ’bout to tell you, Maw Maw,” Grace had said sweetly. “I was playing with a baby, but she had blood on her face. I was scared.”

“When you had this dream, baby?”

“Just now, Maw Maw, while you was down by the river.”

Maw Maw should have been surprised by her granddaughter’s vision and the synching of their connection to what was to be, but she knew better than to question what was natural, true. It was time. “Blood ain’t nothin’ to fear, chile,” Maw Maw said simply. “It got your mama and daddy in it, me and my mama, too. Being scared of blood is like being scared of yo’self.”

* * *

Grace felt something in her stomach, though it was far from her idea of joy. It felt more like what she imagined the hatchet felt like on the neck of a freshly rung cock headed for the pot. She wanted to let Maw Maw know right away that she got her monthly—wanted to know what was to come next. She could count on her grandmother only to tell her the truth. Her mama, Bassey, had long ago traded in what Rubelle taught her about menstruation for what the Bible, the pastor, and the rest of the men had to say about it, so she was tight-lipped on the subject. The most Grace got out of her was that this was a woman’s lot—the curse of Eve. But Maw Maw, she knew nothing of temptation, disobedience, and atonement—of apples and talking serpents with tricky tongues. What she was sure of was what the women who spanned the generations before her were sure of, too: menstruation was a gift. The blood carried the ingredients of life: purification. Intuition. Syncopation between the rhythms of body, nature, God. Her talking to her granddaughter about it became more urgent as Grace’s hips began to stretch the fabric of her flour-sack dress and her buds got round and full. “Mama told me, she say, ‘When you become a woman, the moon will make the waters crash the shores in your honor,’” Maw Maw had told Grace on more than one occasion. “She say Simbi will make a dance in your womb.”

Maw Maw was heading for the clothesline with a freshly washed sheet when she saw her granddaughter walking slowly through the outhouse door, practically doubled over; instinctively, she knew why Grace looked pained, but she asked the child anyway. “What ails you, gal?” Grace’s answer made Maw Maw toss her head back and laugh from her gut. “Come here,” she said, extending her arms and folding Grace into her bosom. “Oh, Simbi gone dance tonight! Go down there in them woods and scrape up some cramp bark—let Maw Maw make you a little something to ease that pain.”

Grace did as she was told, only to emerge from the brush to see a white man riding bareback on a horse, rushing the animal practically up to her grandmother’s nose. He didn’t bother hopping down; just tipped his hat and got to it: “Granny, I need you over to the house. Looks like Ginny getting ready to have that little one.”

“Good day, Mr. Brodersen,” Maw Maw said calmly. She was not in the least fazed by the man’s gruffness; indeed, she was used to—and slightly amused by—how direct and bossy the white folk tended to be with her when they were procuring her services. Like she was beneath them, even though they were standing in her yard, always in a huff, always desperate, looking for her to step into the middle of a miracle. Hell, most of them were in the same predicament as the colored folk they looked down on: not a pot to piss in, and barely a window to throw it out of. They paid with chickens and promises just like everybody else, except they did it with expectation rather than gratitude. Maw Maw didn’t concern herself with the particulars of it all, though. The only thing that mattered to her was her divine mission: assisting in the safe arrival of new life into the world. Color was not specified in her soul contract. “’Bout what time her water broke?” Maw Maw asked politely, shielding the sun from her eye as she looked up at Brodersen.

“Water came about thirty minutes ago,” he said.

“And her pains? ’Bout how far apart are they?”

“She got to hollerin’ straight off, but she only had the one pain before I left.”

“Well, this ain’t her first baby, so ain’t no telling if this one here gonna take its time or come on out and see the world, is it, Mr. Brodersen?”

“I reckon not, Granny,” he said, using the nickname the white folk called Black midwives.

“Well, let me go on ahead and get my bag. Shouldn’t take me no more than about an hour to get over, lessen ol’ Aaron is here and he agree to drive me to yo’ place. In the meantime, you know what to do, and that’s exactly what you did the last time I came over there to catch those sweet babies a yourn. Put the water on the stove, get your bottles and sheets in place, and make your lovely wife as comfortable as possible.”

“Yes, ma’am,” Brodersen said, tipping his hat. And with that, he rode off into the direction of the Piney Tree Mill—the largest employer of the town of Rose. To get to it, his horse would have to cross Piney River by way of the Piney River Bridge, and to get to his home, he’d have to circle around the huge wooden and steel building, where freshly cut trees went to be shaved, chopped, ground, and pulped and white men worked hard and Black men worked equally hard but got 60 percent less money pressed into their palms come Friday evening. White men used that extra money they made to live in the tiny town behind the mill, where Black folk found themselves only if they were there to work for the white families who lived segregated lives in their segregated community with segregated ideals—and even then, Black folk didn’t find themselves there after sundown. The only somebody who was safe there was one Rubelle Adams—the granny whose hands were the first to touch practically three generations of white Rose’s residents. Ruby was neither proud of nor ashamed of this fact. It was what it was.

And now her granddaughter would join her in being the Negro who could visit white Rose in the dark. “Come on in here, baby,” Maw Maw said to Grace, signaling to her granddaughter, who’d stood immobile by the wash line, waiting for the white man to get on. “Let me make you some tea and talk to you a bit. It’s time.”

* * *

From the moment Maw Maw had seen the vision of Grace catching babies, she dutifully set about teaching her granddaughter the ways of the women who wait on miracles—the ways of her own self. And now, on this day that the spirits saw fit to make her capable of producing her own miracles, Maw Maw would bring Grace along to her first birth.

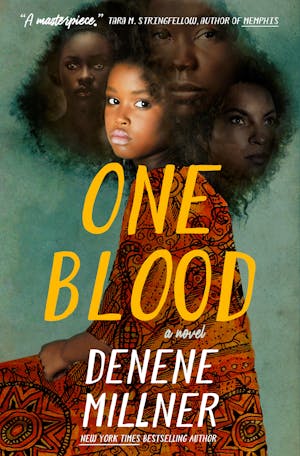

Copyright © 2023 by Denene Millner