INTRODUCTION

What’s the point of biography if it doesn’t reveal secrets?”

That was the question posed by Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis to me in January 1983 when she was an editor at Doubleday & Company in New York. I was a young newspaper reporter at the time who’d just been signed to write a biography of Diana Ross, a book whose publication Jackie had championed. I was sitting in her office, which was small and cluttered with just one window. My eyes scanned her desk. There was a square, crystal container holding different colored pencils, all efficiently sharpened. An ashtray overflowing with cigarette butts. A stack of art books and a couple about dance. Two empty foam coffee cups, two unfinished pastries. A silver-framed picture of her children, Caroline and John, with her mother, Janet Auchincloss. On the wall, just a poster of famed ballet dancer Rudolph Nureyev. I searched the room for her husbands, President John F. Kennedy or Aristotle Onassis, but there were no pictures of either.

“I just adore Diana Ross,” she told me. “She’s so… what’s the word I’m looking for?” She gazed at me for a moment before it came to her. “… enigmatic. Speaking of which,” she added, “do you know Michael Jackson?” I told her he was a friend. “Then, we should definitely talk about him one day,” she said. She was interested in acquiring books by or about public figures who had private lives readers would find unusual or surprising. “Like it or not, a person’s secrets are what makes any biography worthwhile,” she concluded. “Otherwise, what’s the point?”

How ironic, coming from a woman known for guarding her own secrets, especially since Jackie had so much trouble with biographies about herself. There was the first one by Mary Van Rensselaer Thayer in 1960, which caused a rift between Jackie and her mother (a matter I explore in this book for the first time). There was one by William Manchester in 1967, which resulted in litigation. There was Kitty Kelley’s in 1978, which caused a dispute between Jackie and her half brother, Jamie Auchincloss. Many dozens of others were published without her approval. Maybe that’s why Jackie had trouble balancing her own editorial mandate to demystify celebrities with her more natural instinct to protect them. That’s what she ended up doing for Diana Ross with my first of two books about her, Diana Ross: A Celebration of Her Life and Career, published by Doubleday in 1985. Four years later, in 1989, I authored another book about her, Call Her Miss Ross. Whereas the Doubleday book was not successful in the marketplace, the second became a New York Times bestseller.

About a month after the publication of Call Her Miss Ross, I was having lunch with its editor, Hillel Black, at the Lotos Club in New York, one of the oldest private literary clubs in the country. Jackie happened by and joined us. As we chatted, she compared the two Diana Ross books. “Obviously, the reason the second one worked so well,” she observed, “is because, unlike the first one we published, this one is very revealing.” Hillel and I glanced at each other. I wanted to say, “The other one was, too, before it was edited.” I didn’t have to, though, because she came to it on her own. “Doubleday did an ambitious edit on that first book, didn’t we?” she asked. I nodded. “Well, that explains it,” she concluded. “That was our big mistake.”

Jackie then confirmed a story I already knew. In February 1983, she and Doubleday’s president, Sam Vaughan, had a meeting with Diana Ross and her literary agent, Irving “Swifty” Lazar. Fiercely protective of her privacy, Miss Ross sought to stop publication of my first book. In its place, she offered Jackie her autobiography, but with one caveat: it would “include no personal details, whatsoever.” Being gracious, Jackie said she’d give the odd proposition some thought. Before leaving, Diana asked what Doubleday intended to do about my book. Jackie told her not to worry about it.

A month later, Jackie passed on Diana’s book. She did offer, however, to send an advance copy of mine to Diana and Swifty for their review. They were given permission to cut anything they didn’t like. I knew nothing about this arrangement until sometime later. When the manuscript finally came to me for my own review, a lot of it was edited. To this day, I don’t know if that was Diana Ross’s doing or Swifty Lazar’s. Obviously, I wasn’t happy about it, but I was young, and it was my first book so… what did I know?

Years later, with a glint in her eye, Jackie concluded, “So, in the end, it was your book that ended up with no personal details whatsoever, and you see where that got us.” She smiled and added, “Congratulations on finally doing it the right way. I can’t wait to read it.”

Her surprising deal with Diana Ross makes sense when one considers how diligently Jackie worked to maintain her own privacy. Other than the few interviews she gave after the assassination of her husband, President John F. Kennedy, in 1963, she had always been careful not to reveal much about herself. She never did the introspective Barbara Walters interview. She never wrote the insightful memoir.

Like most people, I had many questions when I first met her. As she spoke, I couldn’t help but wonder who she really was and how she viewed herself. Her life had been filled with as much trauma as reward, all of it playing out before the whole world. After everything she went through, where did she draw her strength from, her confidence, her wisdom? There she sat before me, one of the most famous women of all time, open, candid, and available. It wasn’t her grace, charm, or intelligence that surprised me—one would certainly expect that of Jackie—it was her trusting nature. She made me feel as if I could ask her anything. There was just one problem: I wouldn’t dare. It somehow felt unconscionable. How could I take advantage of her by returning her to any dark time in her life? Looking back all these years later, I think her great secret weapon was her basic trust in humanity. She believed people to be essentially good and had faith that no one would ever be so unkind as to quiz her about her painful past. It’s how she survived in New York all those years, walking freely, trying to be “normal” while being stalked by photographers though rarely stopped by passersby. Maybe it was also one of the reasons she was able to maintain her aura of mystery. Perhaps she got away with never talking about her life simply because no one could bear to ask her about it.

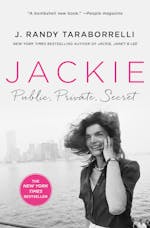

Though I’ve written four previous books related to Jackie and her families, the Bouviers, Auchinclosses, and Kennedys, this is my first full-scale biography of her. When I started it three years ago, I had to wonder if there was more to report given all of the previous books. In the end, I found that the biggest surprises had to do with placing well-known stories into their proper context. For instance, I often reported on her marriage to Aristotle Onassis, but not until this book did I understand its purely transactional nature and the reasons Jackie allowed him to continue his love affair with Maria Callas. Also, I knew she’d quit her job at Viking Press due to disagreement over a book. Not until this research did I understand that her departure also had to do with prioritizing family over career, primarily the care of her mother. I also never understood, until now, her unusual relationship with Maurice Tempelsman. I now recognize that she made the same choices with him that her mother had made with her second husband, Hugh Auchincloss. Speaking of Jackie’s “Uncle Hughdie,” this is the first book to delve into her close relationship with him, one so important he gave her away at both her weddings.

Jackie’s half brother, Jamie—Hugh was his father—told me, “Our mother used to say, ‘Sometimes it feels to me like Jacqueline is completely unknowable.’ At the same time, a paradox about her was that she could occasionally be too revealing, such as after the assassination, when she couldn’t stop talking about it and repeatedly told the same stories. We all knew, though, that this was her trauma speaking.” Indeed, it also wasn’t until researching this book that I fully grasped Jackie’s continued suffering over what happened to her husband, the president. Obviously, she went on with her life, but she never got past his murder, or so she confessed to her former lover, John Warnecke, in the weeks before her death.

I’ve written about the Kennedys for the better part of the last twenty-five years. In doing so, I’ve conducted many hundreds of interviews with family members, friends, and other associates who are now gone, some for many years. You’ll find many of their memories of Jackie memorialized in this book. I felt a responsibility to them to go back over decades’ worth of tape recordings and transcripts in order to tell their stories as accurately as possible. I also reviewed many letters from family sources invaluable to me over the years, clarifying stories and verifying information, as well as diaries, calendars, and other important mementos. I was also able to interview many intimates who now feel much freer to talk about Jackie, almost thirty years after her death in 1994.

I’m honored to have known Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Onassis in the small way I did, certainly not as a friend but just as someone whose path somehow managed to cross my own. I hope this book brings you a bit closer to this remarkable woman, especially those rare instances when she’s maybe not her best self, when she falls prey to anger or insecurity or jealousy. It’s in those unguarded moments we can recognize that she really was just human like the rest of us, not that she ever tried to be anything else. It’s we who were guilty of trying to make her something she wasn’t and never wanted to be—not a mere mortal but, rather, some sort of mythological figure.

John Warnecke told me that, in 1989, about a week before her sixtieth birthday, Jackie observed, “I have three lives. Public, private, and secret,” thus, the title of this book. While she didn’t elaborate, it seems obvious that “public” was the life people thought they knew; “private” was the one about which they gossiped; and “secret” was the one about which they had absolutely no idea. To a certain extent, though, isn’t that true of all of us? No one of us is an open book. We’re all mysterious in our own ways with the same three lives—public, private, and secret. Where Jackie is concerned, I strove to make this book primarily about that last one, the “secret” one. If my job as a biographer is to invade the privacy of my subjects—and I feel certain, based on our conversations, that Jackie would agree with this mandate—then, hopefully, in these pages, you’ll learn a few things about her you didn’t know, maybe even a secret or two. After all, as the lady herself so aptly put it, “What’s the point of biography if it doesn’t reveal secrets?”

J. Randy Taraborrelli

January 2023

“NOBODY KNOWS THE REAL JACKIE”

NOVEMBER 22, 1963

Every time we got off the plane that day, three times they gave me the yellow roses of Texas. But in Dallas, they gave me red roses. I thought, how funny, red roses. The seat was full of blood and red roses.

Some said it sounded like a crack. Others, a pop or a firecracker. Maybe a cherry bomb. Jackie Kennedy thought it was the backfire of a motorcycle. Confused, she watched as Jack grabbed his throat and lurched to the left. Then, there was another bang, and another.

Rifle shots, all. Three in the course of less than five seconds.

Jack turned and I turned back, so neatly, his last expression was so neat. He had his hand out. I could see a piece of his skull coming off. It was flesh-colored, not white. He was holding out his hand and I can see this perfectly clean piece detaching from his head. Then, he slumped in my lap. His blood and brains were in my lap.

JANUARY 20, 1961

She was so proud, it was as if she could feel her heart swell.

In the long history of the world, only a few generations have been granted the role of defending freedom in its hour of maximum danger. I do not shrink from this responsibility, I welcome it. I do not believe that any of us would exchange places with any other people or any other generation. The energy, the faith, the devotion which we bring to this endeavor will light our country and all who serve it—and the glow from that fire can truly light the world.

America’s new First Lady, Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, sat serene and beautiful between Mamie Eisenhower and Lady Bird Johnson as she watched President John Fitzgerald Kennedy address the nation for the first time, its thirty-fifth president.

And so, my fellow Americans: ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country. My fellow citizens of the world, ask not what America will do for you, but what together we can do for the freedom of man.

Jackie thought it had been a magnificent speech. “I had heard it in bits and pieces many times while he was working on it in Florida,” she later said. “There were piles of yellow paper covered with his notes all over our bedroom floor. That day, when I heard it as a whole for the first time, it was so pure, beautiful, and soaring that I knew I was hearing something great. And now I know that it will go down in history as one of the most moving speeches ever uttered—with Pericles’ Funeral Oration and the Gettysburg Address.”

At forty-three, Jack Kennedy would be the youngest president in American history, and also the first Roman Catholic. His election felt like a new beginning, a fresh and exciting start after the staid Eisenhower years. Square-jawed, handsome, and bursting with vitality, he looked impeccable in his formal day dress and striped trousers. Though he didn’t wear it for the oath, a top hat completed the look—an Inauguration Day tradition for U.S. presidents such as Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry Truman. With Jackie at his side, Jack had been sworn in taking his oath on a Catholic Douai Bible that had belonged to his maternal grandfather, John Francis “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald.

For this important day, Jackie had her designer, Oleg Cassini, create a long, fawn-colored wool coat with a sable collar and matching sable muff for her hands. Completing the outfit would be the fur-trimmed, beige pillbox hat designed by Halston—a look she would popularize in the States and abroad; still to this day when people think of pillbox hats, they think of Jackie.

Looking back, it’s hard to believe how young she was. She was just thirty-one, and the eyes of the whole world were on her. Maybe Jackie wasn’t beautiful in the conventional sense—her teeth weren’t perfectly aligned, for instance—but she was so vital and engaging she gave the impression of rare beauty. Her face was clear and luminous though a bit fuller after just having given birth less than two months earlier. Without makeup, people were always astonished at how girlish she seemed. “But all dolled up,” her doting father, Jack Bouvier, used to say, “no one can beat my Jackie in the looks department.” Her eyes were probably her most spectacular feature, large and intelligent, soulful and deeply brown. Tall and slender, she always moved with unaffected grace. “She just has a way,” her stepfather, Hugh Auchincloss, would say. “Jackie’s way.”

Even given her youth, Jackie had already lived a rarified kind of life, especially in the last seven years as the wife of a senator and then president. She never could have imagined herself as a public person—“I’m actually not fond of the public,” she had said—but while stumping for Jack in his campaigns, she learned a lot about herself. She was tougher than she knew, and more charismatic, too. People gravitated to her, and, much to her surprise, she welcomed it. Even though she had reservations about what the future would hold for her and her family, she was ready to steel herself for the challenges ahead as First Lady. “As frightened as I was, I was exhilarated, too,” she would tell her friend Joan Braden many years later. “You know how it is when you’re on a roller coaster? You’re scared, but excited too and apprehensive and you feel as if what’s about to happen will be fun and unforgettable. That’s how I felt when Jack was inaugurated. I felt like as worried as I was and as nervous as I was about what would happen to my family, my children, I was excited in equal measure. I was happy for Jack, too,” she concluded, “because, my God, how he deserved it. How he deserved every bit of it.”

She was ready to commit to her new endeavor—that is, if she could just feel like her old self.

Jackie still wasn’t well after giving birth to her and Jack’s second child, John Jr. Bone-tired and headachy, she was in a sort of daze after having taken heavy doses of Dexedrine for her nerves. Her mother-in-law, the ever-stoic Kennedy matriarch Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy, was overheard saying Jackie was taking too long to recover. She’d had nine children, she proudly noted, and bounced back quickly after each one. “But have you ever had a Cesarean delivery?” Jackie’s mother, Janet Auchincloss, wanted to know. Rose was taken aback by the personal question. The answer was no. “Then, you don’t know what it’s like, do you?” Janet asked. “So perhaps it would be best if you didn’t have an opinion about it.” It was often tense between the mothers-in-law, even though Rose did try to keep the peace. Her son’s was a political marriage, after all, and Rose knew it only served the Kennedys to have a good rapport with the Auchinclosses. It’s just that the Kennedys had political ambitions and the Auchinclosses didn’t, so Janet wasn’t quite as motivated.

“Family tensions aren’t unusual in heightened moments,” wrote Jackie’s stepbrother, Yusha Auchincloss, later. He added that when the stakes are as great as they had been on that day, it was only natural that nerves would be frayed.

Confusion about the seating arrangements for Jackie’s mother and stepfather at the inauguration didn’t help.

Jackie’s half brother, Jamie Auchincloss—twelve at the time—watched the inaugural proceedings seated directly in front of his brother-in-law, the new president. Next to him was his sister, Janet Jr., his stepbrother, Yusha, as well as other Auchinclosses and Bouviers. All of them were in choice seats near Eleanor Roosevelt and Adlai Stevenson, all of them except for Jamie’s parents, Jackie’s mother and stepfather. When he searched the crowd for them, he found them out in the distance facing him and, thus, the back of the president. Surely, this was a mistake. “I had a sinking feeling,” he recalled, “because there was my mother, sitting up impatiently way out there, and even from that distance I could see she was fuming. It was especially embarrassing since she’d just hosted a luncheon for the Kennedy, Bouvier, and Auchicnloss families. Many people who may not have been familiar with her before now knew she was the incoming First Lady’s mother. Some were pointing, as if surprised.”

Adora Rule, Janet’s assistant, who attended the inauguration and was seated with the Auchinclosses behind the president, recalled, “After the inauguration, as we left the Capitol, Mr. A. made a beeline to me. ‘Where’s Tish?’ he asked. ‘We need to speak to Tish.’ He was asking about Jackie’s new social secretary, Letitia Baldrige. She was already at work, I told him. The White House changed hands at exactly noon, and Tish was making sure there were no snafus. Mr. A. looked at me with concern and said, ‘Mrs. Auchincloss is saddened by our seating. She’s practically in tears. How could that have happened?’ I had no idea. Then, on the bus headed to the Mayflower Hotel for the buffet luncheon, which was to be hosted by the Kennedys, he leaned in and whispered in my ear, ‘Jackie did it on purpose.’ I was surprised. ‘That can’t be true,’ I told him.”

Adora had known Jackie since she was hired in 1953 to assist with arrangements of her and Jack Kennedy’s wedding reception at the family’s homestead, Hammersmith Farm. While she had witnessed many tense and argumentative moments over the years, what Jackie was being accused of now was more spiteful than Adora could ever have imagined.

When one considers the tragic way the Kennedy administration would culminate in a little more than a thousand days, it seems ironic that it would commence with bruised feelings over something that, in light of later tragic events, might seem trivial. But, at the time, it felt hurtful, at least to Jackie’s mother and stepfather. After all, though they certainly had their differences, from the day her daughter was born, Janet had been Jackie’s biggest champion. “She was my heart,” is how Janet later put it, “no matter how much we fought, and boy did we ever fight.” For her to be stripped of the privilege of looking at Jackie’s shining face as she became the nation’s third-youngest First Lady seemed unfair. Maybe Jackie felt she had good reason to slight her, but to also deprive Hugh? All he’d ever done since the time she was twelve and moved into his home after he married her mother was to care deeply for her. Thanks to him, she’d enjoyed a rich, privileged life. He thought of her as his own, and his pride in her was equaled only by her mother’s. It all seemed wrong. How had things spiraled so out of control?

“I know Jackie,” Adora stated with confidence, “and she’d never do anything like that.”

Hugh couldn’t help but chuckle at her naivete. As much as he loved Jackie, and felt he had a rapport with her, he was still often completely baffled by her behavior. She was a woman of contrasts. Her life had always been one of great highs and lows, and her responses often unpredictable. She was like her mother—a total enigma. “Kiddo, you may think you know Jackie,” Hugh told Adora, “but take it from me, nobody knows the real Jackie.”

Copyright © 2023 by Rose Books, Inc.