1A World on the Brink of War

BENEATH A GRAY winter sky, Georgette “Dickey” Meyer watched plane after plane depart the Boston Airfield. They were headed for Worcester, Massachusetts, where a historic flood had cut off every road into the small city. The only way to deliver much-needed supplies was by air. Dickey, a fledgling teen reporter, had pitched the idea of covering the airlift to the Boston Traveler, a local newspaper that had given her the tentative green light. But to really get the story, and secure publication, she’d have to make her way aboard one of the supply planes.

Having spent so many hours watching them take off and land, she knew all the pilots by name. Most of them recognized her too since a teenage girl standing on the edge of the tarmac proved a unique sight. Getting a ride to cover the story wouldn’t be a problem if she would only ask. But her mother, Edna Meyer, was the kind of woman for whom worry was a religion, and she had made Dickey promise never to set foot in an airplane. Dickey had kept her word until now, when necessity required her to break it.

She glanced at her watch. Her test on flight dynamics at MIT, for which she had failed to study, had undoubtedly begun. She had to get onto one of those planes if she was to keep her place in college. The only way to make up the test was to prove she had been gainfully employed at the time of its proctoring, since at that time, in 1935 at the nadir of the Great Depression, earning money had to take precedence even at this elite institution.

Despite her current predicament, Dickey’s start at MIT had been promising. Graduating two years early as valedictorian from her high school in Shorewood, Wisconsin, she had been accepted as one of only three women into the 1934 aeronautical engineering class. Grounded by her promise to her mother, Dickey had figured learning to build planes would be a close second to actually flying in them.

This turned out to be far from true. Blackboard equations of force and lift paled in comparison to the real thing. Almost from the first, Dickey started ditching classes to come to the Boston Airfield. Her grades had slipped a little at first, and then a lot. Now she was in danger of losing her scholarship and, with it, her ability to stay at university.

One of the last planes to depart began to cue up at the end of the airstrip. Dickey took a deep breath, shored up her courage, and ran.

“Captain Wincapaw!” she shouted. “I’m an MIT student trying to sell a story to the Boston Traveler. Have you room for me?”

“If you can find room aboard after the bread is loaded, come ahead,” he called back.

Dickey hoisted herself through the cargo door and slid between the crates. The engines roared, the wheels started to lift from the ground, then, suddenly, flight. She recorded her first angel’s-eye view with the language of a poet. “Green rolling earth, white concrete highways, gray sky and a black rain cloud back Boston-way.” Nothing on the ground compared.

Soon thereafter, Dickey flunked out of MIT.

She went home to Shorewood where her parents, Edna and Paul, insisted she get a job. Dickey happily complied, quickly finding employment at the local air circus where she worked as a secretary and took part of her salary in flying lessons. She practiced loops and rolls and spins above green fields dotted with dairy cows. Back in the hangar beneath airplane wings, she practiced French kissing with the pilots.

Displeased with their daughter’s maneuvers in the air and on the ground, Edna and Paul soon packed her off to Coral Gables, Florida, to live with her grandparents. They hoped she might settle down in this quiet Miami suburb of sea breezes and citrus trees. But Dickey had no interest in the well-trodden road, or roads at all, really. She soon found employment at the Tenth Annual Miami Airshow as its city editor, in charge of publicizing its events. The job suited her just fine, as did the salary of $15 a week, a princely sum in the doldrums of the Depression to which not even her overprotective mother could object.

Then, as the calendar approached 1939, things in the world began to change. The wheels of the American economy started to turn once again, albeit slowly. Meanwhile, in Europe, Adolf Hitler had undemocratically seized power while his National Socialist German Workers’ Party espoused a platform of violence and bigotry. But the machinations of international politics barely crossed Dickey’s mind when early in the new year her redheaded, cigar-chomping boss ordered her down to Cuba to help promote Miami’s sister airshow in Havana. Being both ambitious and industrious, Dickey also secured an assignment from The New York Times to cover the event’s flyers for its aeronautical section.

The crowd oohed and aahed as the first pilots executed their tail-slides and stall turns over the Havana Airfield. But Dickey kept her eyes and her pencil trained on the show’s star, currently taxiing into takeoff position. Captain Manuel Orta, chief of the Cuban Air Force and the capital city’s own hometown hero, would be performing the day’s most difficult and dangerous trick: an outside loop, which requires the pilot to successively pass through a dive, inversion, and a climb before returning to normal flight.

The audience waited with both anticipation and confidence as Orta began his dive. Here was Cuba’s ace pilot, for whom surely nothing could go wrong. His plane moved into an inverted position, and it seemed nothing would. But, as he began to pull up, his plane began to shake against the sharp blue sky. Orta gunned the engine and it looked for a moment like he might come out of it. Then came a “splintering, thundering, echoing crash,” as Dickey wrote. Instinctively, she began to run toward the wreck, her low-slung heels sinking into the soft green grass.

A soldier tried to block her way.

“Prensa!” she shouted. Press!, and ran past.

The destruction had been total. As Dickey edged closer, she saw that “Captain Orta’s gleaming propeller blade had become his executioner’s sword.” Back to the edge of the grass, she tried to clear her mind. It was the first death she’d seen in her young life. The romance of flying suddenly became tinged with tragedy. But she knew she had a job to do.

Collecting herself, she began to run toward the terminal’s only phone booth, composing his epitaph as she went: “Captain Manuel Orta, 31, chief of the Cuban Air Force, was killed today when his Curtiss Hawk fighter plane crashed during an air show in front of 17,000 spectators, including his wife and…”

When she arrived, heaving for breath, she found the phone booth already occupied by a man in a white linen suit. She strained to hear him but couldn’t make out his words over the pounding rush of blood in her ears. Summoning up all her midwestern manners, Dickey resigned herself to waiting.

Her restraint seemed to pay off when he hung up. He even helped her connect her call. Too distracted to wonder why a stranger would have the number to the Times’ aeronautics desk, Dickey offered a beleaguered thank-you as the phone rang. Her editor took down her story and sent it to the print shop in time for the deadline. Distracted by a confused mix of pride and grief, Dickey failed to notice that the man was waiting for her until she nearly ran into him.

“I wouldn’t have connected you with the competition so quickly except that I’d already scooped you,” he said with a kind of stern encouragement.

Dickey blinked, confused.

“I’m with the International News Service. We’ve had the flash for five minutes now. Next time, girl, I wouldn’t depend on the other reporters to put you in communication with your office.”

For a moment the air vanished from beneath her wings. But she took it in stride, returning to Miami with a determination to be more self-reliant. In any case, all was not lost. Her article had run in the Times and a few weeks later, the other reporter happened to mention the story to a group of friends. One of them turned out to be Theon Wright, the newly appointed publicity chief of Howard Hughes’s Transcontinental & Western Air, later known as TWA. Impressed by her pluck, Theon called to offer Dickey a job as his assistant. She was to report to New York in ten short days.

* * *

IN THE SUMMER of 1939, she felt at home in the ceaseless and syncopated rhythm of New York City’s streets. She took a room the size of a prison cell in a Brooklyn Heights boarding hotel that suited Dickey just fine. She never was one to stay in.

Weekdays were spent at the TWA offices on Forty-Second Street, where she toiled at typing and addressing thirteen copies of each of the company’s many press announcements. But between long stints at the keys, she could glance out of her tiny cubicle’s window onto the Chrysler Building, that pinnacle of Art Deco design epitomizing the grace and extravagance of New York City. Besides, the job wasn’t all routine. As the publicity director’s assistant, Dickey got to accompany Theon at major aviation events. She rode into a pink winter sunrise in an airline limousine. She flew in the first airplane to land at Idlewild Airport on the day Mayor Fiorello La Guardia cut its ribbon. She traveled coast to coast on TWA’s famous transcontinental flights without a ticket because she was an airline employee. Not bad for a midwestern girl who’d just turned twenty.

Weekends, Dickey did what she did best—explore. Wandering Manhattan’s gridded avenues and streets, she saw the world that called New York City home. Summer breezes and the ring of pushcart bells announced Italian ices on Mott and Mulberry Streets. Cantonese and sandalwood drifted through the air in Chinatown. She dodged clothing racks parading the latest fashions through the Garment District, then grabbed a bite to eat at a corner deli where the pastrami was sliced almost thin enough to see through.

It was a good life for Dickey and she might have gone on living this way indefinitely. But then came the first of September, 1939. The day the world stood still, then doubled the speed of its spin.

As she often did when curious about the news, she walked the few blocks from work to the Times building where the day’s headlines circled its facade in enormous electrified letters. And there it was, the sentence that veered the course of history onto the path of total war.

HITLER OVERRUNS POLISH FRONTIER WITH FOUR PANZER ARMIES

The war that had long been rumbling in Europe finally erupted.

The US Congress immediately began to debate whether or not to enter the war. Neutrality won the day, but President Franklin Roosevelt appealed to the House for the funds to build 1,700 aircraft that could be sold to the embattled Allied Powers. They granted him twice that much and in so doing sent America’s fledgling airplane industry soaring. Dickey knew there had to be an angle in there somewhere, and found it at the Long Island Aviation Country Club.

On an early October Saturday, Dickey held her breath from the ground as Earl T. Converse climbed to 12,000 feet in his Grumman F3F, then dropped into a terminal-velocity dive with his nose pointed directly at his audience. The plane plummeted at 413 miles an hour, about 7 miles a minute. At the last possible second, Converse pulled up. Suddenly reversing such a rapid dive meant the centrifugal force he felt would equal about nine times his ordinary weight, 9 Gs in aviator parlance. Dickey was in awe.

The powerful single-seat F3F was already the aircraft of choice for the US Navy. But with lucrative contracts on the table, Grumman had cut a second seat into this exhibition model for potential foreign buyers to take a ride. No reporter had yet covered it in flight or its groundbreaking maneuverability. When Dickey learned of this, she pitched the story to the Times and bought a ticket to the next airshow. Now all she had to do was persuade its pilot to take her up.

Scanning the audience for anyone with the authority to grant her permission to take a ride, her eyes fell on none other than Leroy Grumman himself, founder of the F3F manufacturer. Striding up to him with casual confidence, she inquired if anyone had ever written about the actual experience of a terminal-velocity power dive and threw in a few details about her tenure at MIT and previous experience as an aeronautical journalist.

“I’d like to read your story myself,” he replied, impressed with her determination, and led her over to the hangar. “Connie,” he said, “I think you’ll find this young lady knows something about airplanes. See that she gets a ride.”

Less than thrilled to be performing another dive, Converse begrudgingly threw Dickey a parachute. “Don’t forget to scream,” he said tiredly. “When your eyes black out, it’ll be from the G. Give your gut a break. Scream so it’ll tighten up.”

“Yes, Mr. Converse,” replied Dickey, who suddenly had the feeling she might be in over her head. Taking a deep breath, she hoisted herself into the plane.

At a mere 6,000 feet Converse put the plane into a gentle dive that Dickey could have executed herself. Having completed the kiddy roller-coaster ride, he turned around and shouted over the engines, “Are you all right? Everything okay?”

Dickey replied by putting her thumb on her nose and wiggling the rest of her fingers, a gesture that more or less meant, “Not quite good enough, Jack.”

Taking her sarcasm personally, Converse charged up to 12,000 feet and slammed the plane into a vertical power dive. Dickey watched the speedometer’s needle push against its limit. As she wrote in her article about the experience, “An irresistible force drives my head into my spine. My legs collapse under me. My back bores into the seat. I try to shout but my cheeks are drawn so tightly that I can’t open my mouth.”

When the plane leveled out again, Converse turned around once more. “Was that better?” he shouted.

Dickey lifted her hands above her head and grinned. Yes, it was.

On the ground, Converse helped her to her feet. The parachute fell from her shoulders as she made a great effort to exhale the words, “Thank you.”

Back in her boardinghouse room, Dickey went to work on her article under the headline A 20-YEAR-OLD GIRL DIVES 10,000 FEET IN A FIGHTING PLANE TO PROVE THAT WOMEN CAN BE COMBAT PILOTS.

Meanwhile, the war in Europe escalated faster than anyone thought possible. Still, Congress refused to join the fight, believing the United States would somehow be spared from the conflict engulfing the globe. Not Dickey, though. Despite her young years, she saw the world teetering on the precipice of a historical moment and knew she had to be a part of it. She also understood that to get in the game, she’d have to become as versatile a reporter as possible. That meant learning how to use a camera.

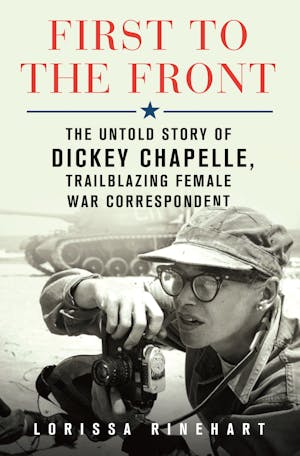

In the autumn of 1939, Dickey signed up for photography classes with TWA’s publicity photographer and World War I veteran Anthony “Tony” Chapelle. Rain, fog, or sun, she and her fellow classmates practiced adjusting their f-stops and shutter speeds to capture the cars humming across the George Washington Bridge. Tony rented a boat launch so his students could capture the bridge’s massive caissons and arched suspension towers against the cobalt blue New York City sky. Then he rented a plane and took Dickey, one of his most promising students, flying with her camera.

Dickey leaned out the side of the open cockpit and clicked until all her film was spent. She might as well have been dreaming. And anyway, she was falling in love with the man at the controls. Short, heavy-built, and more than twice her age, Tony was no Prince Charming at first glance. But what he lacked in looks, he made up for in charisma. Gregarious and confident with impassioned brown eyes, he conducted his class with infectious élan. Dickey was not immune, though early on, she came to understand his charisma went hand in hand with a temper she quickly dubbed Tony’s “Homeric wrath.” He often berated individual students and the class as a whole for their failure to achieve photographic perfection. Nor was Dickey exempt, often finding herself the target of his exacting ire. Still, this proved no barrier.

Tony was no less smitten by this midwestern girl. But rather than love her the way she was, he loved what he might make her and began to sculpt her into his vision of an ideal woman. Young and eager to make it in the man’s world of photojournalism, Dickey fell into his hands like clay. She didn’t mind when he replaced her horn-rimmed glasses and dowdy dresses with red lipstick and formfitting clothes. He draped her in expensive jewelry and photographed her as if she were a model. To be sure, beneath her Rust Belt patina, she was beautiful. And Tony helped her feel that way.

But he made it clear from the start Dickey would never be his equal. He endlessly criticized her angles and exposures. When she related the story of her report on Captain Orta’s tragic death at the Havana Airshow, he ignored her extraordinary audacity as a then teenager and chastised her for not jumping on the fire engine that rushed to the scene. Dickey misread his controlling censures for caring tutelage. When he proposed, she thought she’d hit the lottery. A career, a husband, and an adventurous life all at the age of twenty.

They said “I do” in front of a bank of gladiolas in Dickey’s hometown. Though at first skeptical of this much older man, her parents were soon charmed by his boisterous good humor and confidence. By the time the couple departed, Tony had won their enthusiastic blessing. Dickey took Tony’s last name, Chapelle, which she kept for the rest of her life. Yet his temper that often verged on violence and his tendency toward manipulative behavior proved portentous.

Copyright © 2023 by Lorissa Rinehart