Book details

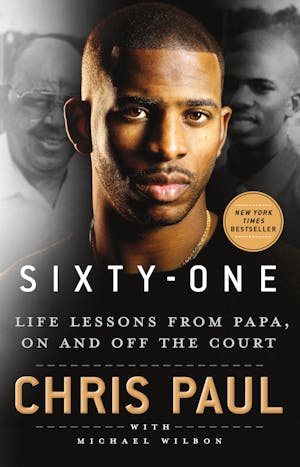

Sixty-One

Life Lessons from Papa, On and Off the Court

Author: Chris Paul with Michael Wilbon

About This Book

Book Details

Instant New York Times, USA Today, Publishers Weekly, and Wall Street Journal Bestseller! A powerful and unexpected memoir of family, faith, tragedy, and life's most important lessons.

The day after future NBA superstar Chris Paul signed his letter of intent to play college basketball for Wake Forest, he received a world-shattering phone call. His grandfather, Nathaniel "Papa" Jones, a pillar of the Winston-Salem community where he owned and operated the first Black-owned service station in North Carolina, was mugged and ultimately died from a heart attack resulting from the assault. His funeral filled the largest church in the county, which held over one thousand people. He was sixty-one years old.

The day after burying his grandfather, Chris was coping the best way he knew how: by playing basketball for his high school team. After pouring in shot after shot, his last attempt was an airball purposely flung out of bounds from the foul line before Chris exited the game. The next day, local news headlines declared that he fell six points shy of the statewide single game high school scoring record. But he accomplished exactly what he set out to do: scoring sixty-one points, one for each year of life lived by his grandfather.

In Sixty-One, Chris opens up about life beyond basketball and the role his grandfather played in molding him into the man and father he is today. He’ll speak about the foundation of faith and family he built his life upon, what it means to be a positive light within your community and beyond, and the importance of setting the proper example for future generations. Most importantly, Chris will talk about his home, Winston-Salem, and the close-knit family and village that raised him to become one of the most respected leaders in all of sports.

Imprint Publisher

St. Martin's Press

ISBN

9781250276711

In The News

"Moving...fresh and refreshing." -- Kirkus

"Candid." --Sports Illustrated

"Unusually moving." --GQ Sports