CHAPTER 1 “ENTERPRISING YOUNG MEN”

It must surely have seemed a sight to the tall, young northerner. A hunter by trade, he had passed through a variety of hamlets, villages, and even blossoming boomtowns in his twenty-three years of meandering west. But nothing had prepared Jedediah Strong Smith for the bustling city of St. Louis, a virtual metropolis looming high over the western bank of the Mississippi River.

It was a chilly April morning in 1822 when Smith, likely alighting from a packet that had ferried him from the green fields of northern Illinois, traversed the narrow riverside boulevard the locals referred to as “Under the Hill.” The street, slippery with mud and horse shit, was teeming with a cross section of humanity—shallow-shaft Ozark lead miners in greasy overalls cashing in company scrip for kegs of rum; restive Indiana farmers bound for the loamy fields opening up along the Boone’s Lick Road abutting Osage Indian territory; peddlers and storekeepers clad in colorful broadcloth frock coats beckoning customers to inspect their wares; and quarrelsome former soldiers of the Republic still wearing their patched and tattered uniforms as they poured to and from the chockablock taverns and bordellos.

Smith passed weathered wooden stalls and narrow storefronts stocked with imports craved by those the fur trade had newly made rich—shimmering cut glassware, handcrafted leather shoes and boots, casks of cognac and wine. There was also a plethora of Black slaves, surely more people of color than he had ever seen, wearing coarse homespun and conversing in pidgin French as they loaded their owners’ carts with bar iron and plow molds.

The river itself was clogged with pirogues and keelboats and even the occasional paddle steamer—an invention so newfangled that children and even some adults flocked to the mud flats to watch the wide-bodied vessels labor through the swirling ochre currents. Between and around the larger craft, rough and weather-browned men maneuvered simpler dugout canoes, constructed from hollowed-out cottonwoods disgorged into the Mississippi from its confluence with the Missouri River twelve miles to the north. The canoes rode low in the water, piled with bundles of beaver pelts and buffalo hides, which their wild-eyed pilots were eager to exchange for powder and lead, for tobacco and smoked pork and flour, and especially for the whiskey and rum carried west down the Ohio River or borne north from Natchez and New Orleans.*

Jed Smith was no stranger to water, having grown up along the shores of both Pennsylvania’s Lake Erie and Ohio’s Sandusky Bay. At the age of thirteen he had signed on as an apprentice seaman on a Lake Erie freighter hauling trade goods between Montreal and what were then the western American borderlands. Yet the sight of the Creole rivermen gracefully steering their sleek vessels to transport hotheaded duelists out to the sandbar in the middle of the river doubtlessly remained a marvel to a naïve country boy. It was on that “neutral” spit of sand nicknamed “Bloody Island,” allegedly subject to neither Missouri nor Illinois law, where aggrieved combatants—prone to quarreling over the affections of the soiled doves of the local sporting houses—would attempt to blow each other’s brains out with their finely crafted Wogdon and Barton flintlock pistols.

Such doings made small sense to Smith, who was descended from a family that had arrived in New England not long after the Pilgrims alighted near Plymouth Rock. Across the generations, his forebears—farmers and artisans—had retained the pious, God-fearing traditions of those early English religious dissidents. One distant relative had earned eighteen shillings a year using his trumpet to summon his New Hampshire neighbors to church each Sunday. And family lore had it that another had praised the Lord for his miraculous survival after a freak eddy had pulled his canoe over Niagara Falls. Like his ancestors, Smith believed that only those whom God elected would receive His grace, and that his righteous deity watched closely to determine who would be saved and who would be damned come Judgment Day. The young man would live his life accordingly.

So it occurred that in the wake of the American Revolution, Smith’s father, also named Jedediah, married the Connecticut-born Sally Strong. The newlyweds moved to the Susquehanna Valley village of Jericho in southern New York State. There the elder Smith and his brother-in-law opened a general store that catered to the river folk settling farmsteads along the long watercourse for which the green vale was named.† Jed Smith was the fourth child, and second son, born to Jedediah Sr. and Sally in January 1799; his mother, a dutiful wife of the era, fulfilled her primary obligation by giving birth to five more sons over the ensuing fifteen years.‡

Young “Diah,” as his family called him, spent his childhood exploring and hunting squirrel, wild turkey, and whitetail deer through the long, green valley’s thick stands of soaring oak, boxelder, and fragrant sassafras, which lent the rolling hills a year-round scent of sweet lemon and cinnamon. The Iroquois had long since abandoned the Susquehanna woodlands, but a fascination with the Indians who decades earlier had called the land their home fired the boy’s imagination. His ears perked whenever Jedediah Sr. told the story of his great-great-uncle being killed by the Narragansetts during King Philip’s War. And as young boys of the era were wont to do, he no doubt scoured the pea vine and clover that carpeted the forest floor, searching for old arrowheads and shards of the clay pots in which the tribe’s women had boiled the venerated “three sisters” of the earth—corn, squash, and beans.

When Jed was twelve his father again caught the westering fever and relocated his growing clan to Pennsylvania’s Erie County, hard by the eponymous lake. It was here that Jed not only honed his hunter’s and boatman’s skills but also met a family that would have a lasting effect on his life. The Simons of Erie County’s North East Township were what passed for aristocracy on the nascent United States’ western frontier. When Jed’s favorite sister, Eunice, married Solomon Simons, the son of the pioneer physician Dr. Titus Gordon Vespasian Simons, a bond between the families was formed. It grew even stronger when Dr. Simons’s daughter Louisa wed Jed’s older brother, Ralph, such that the two families moved as one farther west into northern Ohio.

Dr. Simons had taken an avuncular shine to young Jed, and he began complementing the schooling the boy received from a succession of Methodist circuit riders in reading, writing, and ciphering, as arithmetic was called. He also added a smattering of Latin to the curriculum. When the doctor thought Jed was ready—around the time that British troops were setting fire to the White House during the War of 1812—he gifted him with a newly published leather-bound book detailing the adventures of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark during their momentous twenty-eight-month cross-country expedition to and from the Pacific.

Jed Smith cherished the chronicle, studying the narrative by candlelight, and came to recognize that his treks through the Susquehanna woods and along the craggy shore-scree of Lake Erie and Sandusky Bay were but toddler’s steps compared to the epic accomplishments Lewis, Clark, and their Corps of Discovery achieved. Legend has it that along with a family Bible, Smith carried that book with him for the rest of his life in his kit bag, called a “possible sack,” as it contained everything a hunter or trapper could possibly need.

Now, a decade later and with that possible sack slung over his shoulder, he found himself hiking up from the St. Louis waterfront to the heights of the city proper, where the capacious municipality rivaled only his brief visit to New Orleans two years earlier.

* * *

Although dubbed the “Mound City,” the chain of ancient Native American temple hills and knolls that had once occupied the path Jed Smith now trod through St. Louis were mostly gone, leveled by the New Orleans–born half brothers Auguste and Pierre Chouteau when they laid out the town’s grid. It was Auguste Chouteau’s father, the French explorer Pierre Laclède Liguest, who in 1764 had selected St. Louis—which he named in honor of France’s King Louis IX—as the flood-proof high ground for his fur-trading post. Where feather- and bead-clad members of the Illini Confederacy, a loose affiliation of a dozen or so Native American tribes, had once met to hold religious ceremonies and trade marts, Smith now shared street space with women in flamboyant sun bonnets promenading before finely built houses, many of them constructed of the famed St. Louis clay pressed and kilned into red bricks that were already being exported to Boston and New York.

The ubiquitous brick buildings, such as the new Catholic Cathedral on Church Street with its paintings by Rubens and Raphael and its gold embroideries donated by European coreligionists, were rapidly replacing the old French poteaux-en-terre dwellings—essentially roof-bearing grooved elm logs planted perpendicular into the ground. And at the instigation of the Chouteau brothers, whose ornate homes at the crest of the city’s tallest hill were the town’s jewels, several of the main avenues had even lately been paved. This was much to the consternation of the Gallic traditionalists whose rough-hewn wooden wagon wheels, lacking iron bands, were prone to shattering on the granite cobblestones.

Smith walked west, past the offices of General William Clark, who, in the wake of his epic partnership with Meriwether Lewis, had held several political posts under presidential appointment and was currently President James Monroe’s superintendent of Indian affairs. It has never been ascertained if Smith still carried in his pocket the yellowing newspaper clipping he had torn from the Missouri Gazette & Public Advertiser months earlier. Nestled among the personal notices on page three of the broadsheet—warnings to local merchants against extending credit to spendthrift wives; shopkeepers’ advertisements heralding the recent arrival of barrels of salted mackerel, kegs of Madeira wine, and aromatic “Spanish Segars”—was posted a fifty-seven-word announcement. It was addressed:

TO

Enterprising Young Men

The subscriber wishes to engage ONE HUNDRED MEN, to ascend the River Missouri to its source, there to be employed for one, two or three years.—For particulars enquire of Major Andrew Henry, near the Lead Mines, in the county of Washington, (who will ascend with, and command the party) or to the subscriber at St. Louis.§

The subscriber in question was the lieutenant governor of the newly minted state of Missouri, General William Henry Ashley. Ashley had served as an officer in a territorial militia during the War of 1812 and had subsequently risen to the rank of brigadier general. He saw little need to delineate the tasks awaiting the men he and his business partner and fellow former soldier, the Pennsylvania-born Major Andrew Henry, planned to take upriver. The western fur trade that had swelled St. Louis’s population ninefold to more than five thousand people in the nineteen years since the Louisiana Purchase had also transformed the town into the most thriving “jumping-off point” for the “new” American borderlands—“the Ur-country of the trans-Mississippi frontier,” in the words of the Kit Carson biographer Hampton Sides.¶

Missouri in general and St. Louis in particular “had long been the portal of American expansion,” Sides continues, “the pad where great expectations were outfitted and adventures launched, the place where westering fever burned at its highest pitch.” And for weeks now gossip along both the rough quay-side grogshops and in the city’s gentrified upper quarter had coalesced around one item: the beaver-trapping expedition that would culminate with the forty-four-year-old Gen. Ashley and Maj. Henry, three years Ashley’s senior, re-establishing a fort at the mouth of the Yellowstone River.

It had been years since any company had outfitted up for the mountains. Yet now there were four separate firms racing up the Missouri River. Their managing partners had decided that it was time. Time to re-establish the lucrative beaver trade.

* * *

Through much of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the soft felt coat of the semiaquatic North American rodent classified as Castor canadensis dominated the European clothing market. Though beaver fur occasionally provided the material for collars, jackets, and even full-length parkas popular in China and Russia, it was predominantly craved by European hatmakers who had long understood that the waxlike lanolin contained in the animal’s wool rendered the headgear, whether tricornered or high-crowned, water resistant.** Such was the popularity that between 1700 and the outset of the Henry-Ashley expedition in 1822, markets in continental Europe had purchased nearly forty million pieces of beaver headwear from British milliners.

But even earlier in the colonial period the beaver pelt had, from New England to Virginia, been the veritable equivalent of gold as a unit of barter. In December 1621, only a year after the first Pilgrim settlement was founded in Plymouth, Massachusetts, an initial shipment of American beaver furs left for England aboard the fifty-five-ton schooner Fortune as payment for needed supplies. Within a few years, the Plymouth colonists had virtually abandoned their original plan to sustain themselves through hunting and cod fishing and instead concentrated their economy almost entirely on the fur trade with Native Americans from the north.

Inevitably, by the time Jed Smith arrived in St. Louis, the beaver population east of the Mississippi had, like the Eurasian species, Castor fiber, been hunted nearly to extinction. This left the western United States and Canada as the center of the world’s beaver-pelt trade. The cordilleras dividing the North American continent were ideally suited to the construction of beaver dens, or “lodges,” and early western fur brokers, known as factors, rarely had to travel farther than the Black Hills in present-day South Dakota—some three hundred miles east of the Rocky Mountains—to traffic in Indian catch. By the turn of the nineteenth century, however, this was no longer the case, and yearslong beaver-hunting expeditions into the ruthless Rockies had been necessary since the first decade of the 1800s. This was the tradition that Gen. Ashley planned to revive.

* * *

The widowed William Ashley had never been west of St. Louis. He had, however, partnered up well, as his joint venture with Andrew Henry would constitute Maj. Henry’s return to the granite crags and ridges scraping the western sky. Fourteen years earlier, in 1808, Henry—whose contemporaneous portraits depict a thick-set, slope-chinned countenance with a boyish thousand-yard stare from dark eyes—had signed on with one of the initial outfits venturing into the mountains. That firm, incorporated as the Missouri Fur Company, was the brainchild of Manuel Lisa, a New Orleans–born Spanish American who, in 1802, was granted a contract by French officials to act as the sole trading agent between the Osage Indians and the Mississippi’s downriver merchants.

President Jefferson’s purchase of the Louisiana Territory from Napoleon Bonaparte’s First French Republic the following year eliminated Lisa’s monopoly on America’s western fur trade, and Lisa found himself searching for new streams of revenue. This proved difficult. Missouri’s territorial governor—posthumously discovered to have been a spy for the Spanish Crown—denied Lisa’s application to establish trade routes with Santa Fe, then still under Spain’s colonial rule. Lisa pivoted and instead looked northwest. Recruiting two members of Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery as guides, he ventured up the Missouri River in the spring of 1807 with a party of forty-two men. Reaching the Yellowstone River, Lisa’s outfit ascended the watercourse 170 miles to establish a trading post at the mouth of the Yellowstone’s confluence with the Bighorn. He named his post Fort Raymond, in honor of his oldest son.

If, as the historian Harrison Clifford Dale proposes, “Lewis and Clark were the trail makers [and] Lisa the trade maker,” the news of Lisa’s presence on the Upper Missouri was received with jubilation in the nation’s capital. For it was there in the mountains that Lisa’s venture planted the implicit flag for President Thomas Jefferson’s strategic geopolitical design for the North American continent.

For all his agrarian tendencies, Jefferson was far from a shortsighted statesman. He had sanctioned the Lewis and Clark expedition ostensibly to gain a more accurate assessment of the new lands acquired in the Louisiana Purchase, with a secondary goal of gauging the viability of future oceangoing trade with Asia. The true, underlying objective of the undertaking, however, was to counter festering American concerns over British thirst for the territory northwest of the Rocky Mountains. Sensing that war-torn France and Spain were gradually losing their purchase on the New World, Jefferson feared that England was ready to fill this vacuum. As he presciently had written some two decades earlier in his Christmas greeting to Clark’s brother, George Rogers Clark, “We shall to the American union add a barrier against the dangerous extension of the British Province of Canada and add to the Empire of liberty an extensive and fertile Country.”

Jefferson had cause to worry. Just over one hundred years earlier, in 1670, the English King Charles II had granted a monopolistic royal charter ceding what was then known as Rupert’s Land—the 2.5 million square miles west of Ontario, comprising about one-third of modern-day Canada—to the joint-stock corporation Hudson’s Bay Company. Moreover, the American president was also casting a watchful eye over an upstart fur-trapping outfit called the North West Fur Company, a Montreal-based consortium of predominantly Scottish Canadians whose hunter-trappers were already blatantly poaching on the Hudson’s Bay Company’s western territory.

As the Canada–America border west of the Rocky Mountains remained in dispute, the region that would become known as the Oregon Territory—encompassing the current states of Washington, Oregon, and Idaho, as well as parts of western Montana and Wyoming—was nominally up for grabs. The United States, having just flung the Redcoats back across the Atlantic in its War for Independence, was haunted by the specter that England would now attempt to re-enter North America from the Pacific. It was a British person, after all, who had coined the axiom that possession is nine-tenths of the law.

Moreover, the enemy had a geographic jump. In May 1793, six months after George Washington was unanimously re-elected to his second presidential term, the flame-bearded Scottish explorer Alexander Mackenzie set off from what is today the northern section of Canada’s Alberta province to seek a route to the Pacific Ocean. Thirteen weeks later he reached the shores of British Columbia, becoming the first European north of Spanish Mexico to traverse the breadth of the continent. Eight years later, Mackenzie published the exploratory journals of his trans-Canadian trek. It had a galvanizing effect on President Jefferson and his political circle.

In reaction, Jefferson alternately bullied and cajoled Congress into funding an expedition to explore the far northwest beyond the Rocky Mountains. He appointed his personal secretary, the former army officer and robust outdoorsman Meriwether Lewis, as its commanding officer. The autodidactic Jefferson personally taught Lewis how to calculate longitude and latitude. He also ensured, at the government’s expense, that Lewis was trained by mathematicians, scientists, and geographers in the use of the chronometer and sextant as well as in cartography, botany, and geology. Lewis in turn selected his former U.S. Army commander William Clark, four years his senior, to co-lead the forty-man expedition.

The Corps of Discovery reports regarding the fauna, flora, terrain, and Indigenous tribes it encountered may have held a passing interest for entrepreneurs like Manuel Lisa. But it was the tales of the thousands of mountain streams and ponds aswarm with fat beavers that drove Lisa and others west in 1808. Lisa had turned a sound profit on his first journey into the Rockies. This enabled him to form an even larger trapping expedition the following spring, returning to the mountains with thirteen barges and keelboats crewed by 350 men. These included both the future major Andrew Henry and the well-traveled George Drouillard, the son of a French Canadian father and a Shawnee mother who had served as an interpreter for Lewis and Clark.

During this foray, Henry, acting as his trapping team’s Booshway, or captain, led a small contingent across the Continental Divide in western Montana before dropping down into Wyoming’s Snake River country.†† This was the deepest penetration into the Oregon Country that any American outfit had ever made. But the presence of so many white men from the States encroaching on their territory stirred the ire of the Blackfeet, who had forged a tenuous alliance with the Canadians, trading their beaver pelts for British muskets, shot, and powder. Two years earlier the tribe had clashed with a small scouting party from the Corps of Discovery, with Meriwether Lewis personally killing a Blackfeet brave who attempted to steal his rifle and horse.

George Drouillard had been among Lewis’s company that day and now during Lisa’s second foray into the territory—in a pointed reminder that the tribe had long memories—Drouillard’s mutilated and beheaded corpse was discovered in a clearing, its entrails ritually arranged about the desecrated body. Drouillard, esteemed for the number of grizzly bears he had taken down under Lewis and Clark, had not gone down without a fight. Blood trails and tracks on the ground indicated that the surrounded Drouillard, still mounted and using his horse as a shield, ridden in smaller and smaller concentric circles, emptying his rifle and pistols before leaping from his mount and wielding his tomahawk and skinning knife to the end.

Within the year, the Blackfeet had driven those early, outnumbered Americans from the mountains, with the Indians claiming the scalps of twenty trappers. Their success, however, may have been moot. For though men like Manuel Lisa and Andrew Henry had spent years braving the dangers of the Rocky Mountain high country, the naval blockade thrown up by the British during the War of 1812 was to depress the American beaver market for a decade. The trade curve was only just bending up once again when Jed Smith arrived in St. Louis to call on William Ashley.

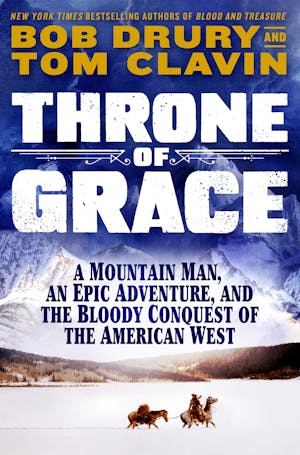

Copyright © 2024 by Bob Drury and Tom Clavin