Book details

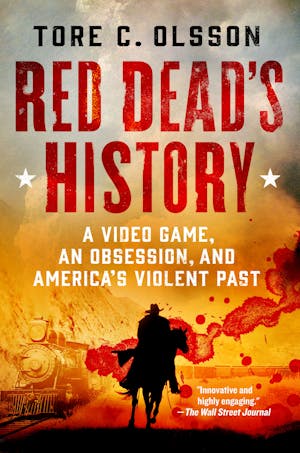

Red Dead's History

A Video Game, an Obsession, and America's Violent Past

Author: Tore C. Olsson

About This Book

Book Details

A pathbreaking new way to examine US history, through the lens of a bestselling video game

Red Dead Redemption and Red Dead Redemption II, set in 1911 and 1899, are the most-played American history video games since The Oregon Trail. Beloved by millions, they’ve been widely acclaimed for their realism and attention to detail. But how do they fare as re-creations of history?

In this engaging book, award-winning American history professor Tore Olsson takes up that question and more. Weaving the games’ plots and characters into an exploration of American violence between 1870 and 1920, Olsson shows that it was more often disputes over capitalism and race, not just poker games and bank robberies, that fueled the bloodshed of these turbulent years. As such, this era has much to teach us today. From the West to the Deep South to Appalachia, Olsson reveals the gritty and brutal world that inspired the games, but sometimes lacks context and complexity on the digital screen. Colorful, fast-paced, and dramatic, Red Dead’s History sheds light on dark corners of the American past for gamers and history buffs alike.

Imprint Publisher

St. Martin's Press

ISBN

9781250287717