Chapter 1

BOSTON

JUNE 1726

I don’t know what made me determined to go to the hanging.

I’d always made a point of avoiding them. I resisted the entreaties of my friends who wanted to be in amongst the throngs of onlookers, ears pricked for the last words and the pious advice of the soon-to-be-damned.

Of course, I’d always been curious. You cannot help but wonder about the face of one condemned. To see his carriage toward the crowd, and himself. To feel the swelling cheers and cries of all the townsfolk, to hear the crack of the felon’s neck snapped like a chicken’s.

I wondered if their eyes were open or closed when their moment came. What happens, in the instant in between being a living, breathing creature, trembling with needs and wants and fears, and being an empty sack of flesh and bone? Is it the same for an old woman alone in her bed with the covers pulled up tight as it is for a man mounting the scaffold before God and everyone? Does an unearthly light of heaven attained shine upon the greasy strings of their hair if they have confessed and repented? Everyone repents at the end. Or so I’ve been told.

I’d heard the moment of public death described often enough, usually by someone with a hand around a glass. But I had always been of too delicate a nature to see for myself. I didn’t like to drown kittens or stomp tremble-whiskered mice and, as often as not, found a way to avoid such grim chores on the occasion Mrs. Tomlinson chose to impose them on me. I even crossed the street from dogs lying dead in the gutter.

But something about William Fly was different. I made up my mind that I would go.

Summer wears long on the Boston wharves, with early sunrise and late nightfall dragging its feet to deliver our relief. And so, the afternoon was stifling in Ship Tavern when I first heard the name of William Fly. The ordinary was generally tolerably cool in summer, being a dim cavern of rooms built of ancient brick, squatting like a naiad’s grotto for almost a hundred years at the foot of Clark’s Wharf. Ship Tavern stands close enough to the harbor waters that a brig can moor nearly at the lip of our door. Well situated to swallow up the passing seamen as they stumble ashore, land-sick and looking for all the things sailors look for when they have been long at sea. But that June day the sun shone especially heavy, bleaching the color out of the air and leaving us all wilted and damp. Inside, the usually cool hollow of the larger dining room had warmed by degrees until it felt like the inside of a beehive oven. The sand on the floor was hot underfoot. The front door stood propped open to catch any whisper of a passing breeze, but the water in Boston Harbor was as flat and slick as molten glass.

I was sitting on an old apple barrel outside, leaning on the brick wall of my home and place of employ, my skirts knotted up to my shins to get some air on my bare and aching feet. I should have been getting back inside to stoke something, or serve something, or carve something, or scour something. Inside the tavern a few men lazed indolently about, looking into their cups, waiting for the day to end. No one was calling my name. Mrs. Tomlinson was I knew not where. As I gazed up the narrow length of Fish Street, I spied not a living soul, save the odd gull perched on a piling or tabby cat slithering amongst coils of rope in search of rats. My heels bumped on the hollow barrel.

I packed a small wad of tobacco and hemp into the slender clay pipe someone had left behind in one of the rooms, sparked it with a few sucks of my cheeks, and settled back to stare over the water, smoke coiling from my lower lip up into my nostrils. Clark’s Wharf is nearly as long as Long Wharf, but older. Half a dozen snows and brigs and a couple of little schooners and sloops rubbed their hulls against the pilings, their lines and rigging creaking. Sails all furled and put away. No one was about. No bent-over boys scrubbing any decks or barefoot figures climbing rigging silhouetted by the sun. Even the gulls were quiet. The water shimmered away to the horizon, low ridges of the harbor islands rising through the orange and yellow summer haze.

I closed my eyes and wished for a ripe apple.

“Cut his hand off,” I heard someone say softly. So softly, it might have been spoken in my mind.

I opened my eyes but saw no one.

“Off! With what?” another voice said, in an accent that hinted at time in Jamaica. So, not inside my head after all.

I got off the apple barrel, ears straining to listen. The voices hadn’t come from inside the tavern. Fish Street was as abandoned as it would be after the Rapture.

“Broadaxe,” said the first voice, who was from somewhere that wasn’t Boston. “As he clung to the mainsheet hanging over the side.”

Someone laughed merrily.

I could hear them clear as a church bell. But where were they?

Presently I discerned the shape of a small rowboat emerging from the haze, its oars dipping and rising in circles. The rowboat contained two boys about my own age, seventeen or so, not more than twenty, in sun-whitened shirts and breeches. The one pulling on the oars wore a checked kerchief over his head to keep the sweat from his eyes. His companion, the Jamaican, wore his knotted around his neck, his hair in tidy twists all over his head. They edged close to the nearest moored brig, and the boy with his back to me leaned on an oar to clear the stern.

I could have gone to help them tie up, but it was too hot. Instead, I sat back on the barrel and drew on my new pipe.

“That’s one way to discharge your sailing master,” the Jamaican said with gravity. “Handless into the deep. One o’clock in the morning.”

“I knew that John Green,” his mate, the not-Bostonian, continued. “Their captain. At Port Royal.”

The rowboat bumped up to the piling almost exactly below my idle feet, grating against the barnacles. The not-Bostonian sprang ashore with a line in his hand and made it fast. I tried to make a ring with my smoke to watch them through, but it came out a cloud.

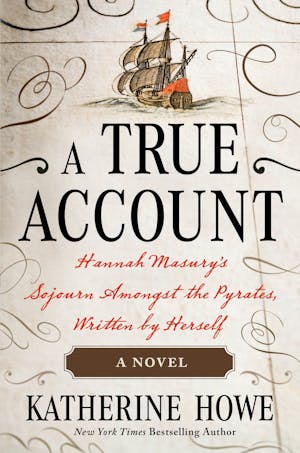

Copyright © 2023 by Katherine Howe