BLAIR

I looked up into the eye of a gun. She’d been that quiet. That fast. At the edge of my vision I’d half seen a figure pass the front window of the Pump’n’Jump gas station, a shadow-walker blur against the red sunset and silhouetted palm trees. That was it. She stuck the gun in my face before the buzzer had finished the one-note song that announced her, made her real. The gun was shaking, a bad thing made somehow worse. I put down the pen I’d been using to fill out the crossword.

Deep regret: Remorse. Maybe the last word I would ever write. One I was familiar with.

I spread my fingers flat on the counter, between the bowl of spotted bananas at a dollar a piece and the two-for-one Clark Bars.

“Don’t scream,” the girl said.

As I let my eyes move from the gun to her, all I could see was trouble. There was sweat and blood on her hand, on the finger that was sliding down the trigger, trying to find traction. The safety switch was off. The arm that held the weapon was thin and reedy, would soon get tired from holding a gun that clearly wasn’t hers, was too heavy. The face beyond the arm was the sickly purple-gray of a fresh corpse. She had a nasty gash in her forehead that was so deep I could see bone. Fingerprints in blood on her neck, also too big to be her own.

Screaming would have been a terrible idea. If I startled her, that slippery finger was going to jerk on the trigger and blow my brains all over the cigarette cabinet behind me. I didn’t want to be wasted in my stupid uniform, my hat emblazoned with a big pink kangaroo and the badge on my chest that truthfully read “Blair” but lied “I love to serve!” I had a flash of distracted thought, wondering what my young son, Jamie, would wear to my funeral. I knew he had a suit. He’d worn it to my parole hearing.

“Whoa,” I said, both an expression of surprise and a request.

“Empty the register.” The girl put out her hand and glanced through the window. The parking lot was empty. “And give me the keys to the car.”

“My car?” I touched my chest, making her reel backward, grip the gun tighter. I counseled myself not to move so fast or ask stupid questions. My bashed-up Honda was the only car visible, at the edge of the lot, parked under a billboard. Idris Elba with a watch that cost two college funds.

“Car, cash,” the girl said. Her teeth were locked. “Now, bitch.”

“Listen,” I said slowly. For a moment I commanded the room. The burrito freezer hummed gently. The lights behind the plastic face of the slushie machine made tinkling noises. “I can help you.”

Even as I said the words, I felt like an idiot. Once, I’d been able to help people. Sick children and their terrified parents. I’d worn surgical scrubs and suits; no kangaroos, no bullshit badges. But between then and now I’d worn a prison uniform, and my ability to help anyone had been sucked away.

The girl shuffled on her feet, waved the gun to get me moving. “Fuck you and your help. I don’t need it. I need to get out of here.”

“If you just—”

My words were cut off by a blast of light. The sound came after, a pop in my eardrums, a whump of pressure in my head as the bullet ripped past me, too close. She’d blown a hole in the Marlboro dispenser, just over my right shoulder. Burned tobacco and melted plastic in the air. My ears ringing. The gun came back to me.

“Okay,” I said. “Okay.”

I went to the register, snuck a sideways look at her. Gold curls. A small, almost button nose. There was something vaguely familiar about her, but during my time in prison I’d probably cast my eye over a thousand troubled, edgy, angry kids who knew their way around a handgun. I took the keys from the cup beside the machine.

“This is a cartel-owned gas station,” I said. I realized my hands were shaking. Soon I’d be sweating, panting, teeth chattering. My terror came on slowly. I’d trained it that way. “You should know that. You hit a place like this and they’ll come for you and your family. You can take the car, but—”

“Shut up.”

“They’ll come after you,” I said. I unlocked the register. She laughed. I glanced sideways at her as I scooped out stacks of cash. The laugh wasn’t humor, it was ironic scorn. Something sliced through me, icy and sharp. I looked at the windows before me, at our reflections. She was looking out there, too, into the gathering dark. No one else was visible. We seemed suddenly, achingly alone together and yet terrifyingly not alone. I handed her the cash.

“Someone’s already after you,” I surmised. She gave a single, stiff nod. I slowly took my car keys from my pocket and dropped them into her hand. When the barrel of the gun swept away from me, it was like a clamp loosening from around my windpipe.

I watched her turn and run out of the shop, get in the car, and drive away.

Through the windows, Koreatown at night seemed to breathe a sigh of relief, to become unpaused. Long-haired youths knocked each other around on the corner. A man returning home from work let the newspaper box slap closed, his paper tucked under his arm. The malignant presence I’d felt out there when the girl had been in the store was gone.

I could have called the police. If not to report the robbery, to report a girl running from something or someone with the furious desperation of a hunted animal, a girl out there in the dark, pursued, surviving for who knew how long. But Los Angeles was full of people like that; always had been. A jungle, prey fleeing predators. I’d give the girl a little head start with my car before I reported it missing. I lifted my shirt and wiped the sweat from my face on the hem, trying to regulate my breathing.

My addiction pulsed, a short, sharp desire that made me pick up my phone beside the register, my finger hovering, ready to dial. I forced myself to put the phone down. The clock on the wall said I had an hour left of my shift. I thought about calling Jamie but knew he’d be asleep.

Instead I went to the ATM in the corner of the store. I slipped my card into the machine and extracted four hundred dollars, about the amount I knew the girl had taken. I went back and put the notes in the register. Though I’d never met the gas station’s true owners, I’d known cartel women in the can, and had picked up enough Spanish over the years to eavesdrop on their stories. The girl, whoever she was, didn’t need the San Marino 13s on her tail. Neither did I.

I hardly looked at the ATM receipt before I crumpled it and let it fall into the bin. It was going to be a long walk home.

JESSICA

“Here’s what I don’t understand,” Wallert said. He’d been saying it all day. Listing things he didn’t get. Waiting for people to explain them to him. Jessica guessed they were probably into the triple digits now of things Wallert couldn’t comprehend. “What the hell did you do on the Silver Lake case that I didn’t do?”

She didn’t answer, just looked at Detective Wallert’s bloodshot eyes in the rearview mirror. Jessica hated the back seat of the police cruiser, didn’t belong there. She was used to the side of Wallert’s ugly head, not the back. A biohazard company gave the back seat a proper clean out every month or so, but everybody knew that it never really got clean. The texture of the leather wasn’t right. Gritty in places. But Wallert was looking at her more than he was driving. Combined with the frequent sips of bourbon-spiked coffee from his paper coffee cup, he was eyeing the road about one in every fifteen seconds. In this case, she was in the dirtiest but likely the safest place in the car. Detective Vizchen, who they were babysitting for the night, sniffed in the front passenger seat when Jessica didn’t answer Wallert, as if her silence was insolence.

“I was there,” Wallert continued. They cruised by a bunch of kids standing outside a house pumping music into the night. “I was in the case. I was available to the guy whenever he needed me. Day or night. He knew that. It was me who came up with the lead about the trucker.”

“A lead that went nowhere,” Jessica finally said. “A lead I told you would go nowhere before you began half-heartedly pursuing it. You weren’t of much assistance to Stan Beauvoir the few times he called on you.”

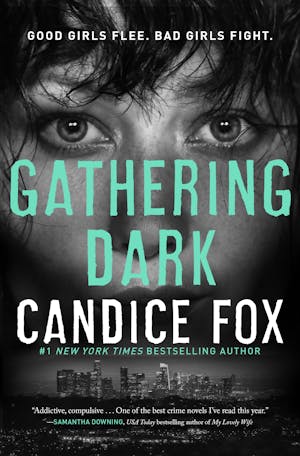

Copyright © 2021 by Candice Fox