Book details

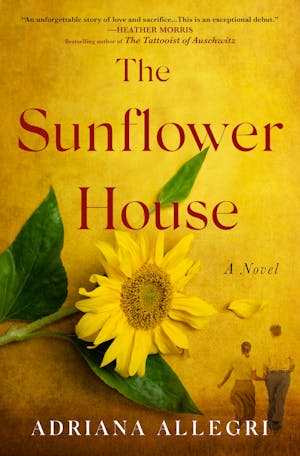

The Sunflower House

A Novel

Author: Adriana Allegri

About This Book

Book Details

Family secrets come to light as a young woman fights to save herself, and others, in a Nazi-run baby factory—a real-life Handmaid's Tale—during World War II.

In a sleepy German village, Allina Strauss’s life seems idyllic: she works at her uncle’s bookshop, makes strudel with her aunt, and spends weekends with her friends and fiancé. But it's 1939, Adolf Hitler is Chancellor, and Allina’s family hides a terrifying secret—her birth mother was Jewish, making her a Mischling.

One fateful night after losing everyone she loves, Allina is forced into service as a nurse at a state-run baby factory called Hochland Home. There, she becomes both witness and participant to the horrors of Heinrich Himmler’s ruthless eugenics program.

The Sunflower House is a meticulously-researched debut historical novel that uncovers the notorious Lebensborn Program of Nazi Germany. Women of “pure” blood stayed in Lebensborn homes for the sole purpose of perpetuating the Aryan population, giving birth to thousands of babies who were adopted out to “good” Nazi families. Allina must keep her Jewish identity a secret in order to survive, but when she discovers the neglect occurring within the home, she’s determined not only to save herself, but also the children in her care.

A tale of one woman’s determination to resist and survive, The Sunflower House is also a love story. When Allina meets Karl, a high-ranking SS officer with secrets of his own, the two must decide how much they are willing to share with each other—and how much they can stand to risk as they join forces to save as many children as they can. The threads of this poignant and heartrending novel weave a tale of loss and love, friendship and betrayal, and the secrets we bury in order to save ourselves.

Imprint Publisher

St. Martin's Press

ISBN

9781250326522