How It All Began

Mankoff introduced the caption contest as part of The New Yorker’s annual Cartoon Issue, and it was judged by the magazine’s staff. The initial goal, said Mankoff, “was to create this odd sort of challenge for readers and discover whether the results were interesting. In other words, we wanted to know how inspiration was sparked when someone was looking at an image with an incongruity in it that called out for a comic line.”1

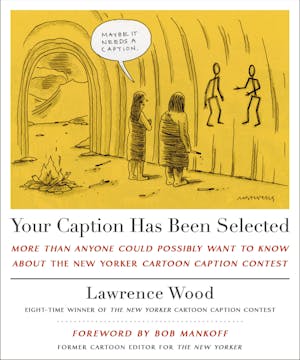

Many readers came up with funny ideas for each annual contest, including the one featuring this drawing by Mick Stevens:

“People got to some of the main humorous aspects right away,” said Mankoff. “Why was the angel in jail? What could an angel have done that was so bad? Would he get time off for good behavior?” But that was just the first step. The real challenge was turning the funny idea into a concise and well-crafted caption. Simon Hatley met that challenge with a practical tip for surviving prison: “I’d lose the dress.”

The annual contests were popular. This one, featuring a drawing by Danny Shanahan, elicited more than fourteen thousand entries:

New Yorker cartoonist Bob Eckstein remembers entering that contest (long before he started submitting his work to the magazine) but doesn’t recall his exact entry. He got a telephone message about his caption from the magazine’s cartoon department, but by that time he had learned there was no cash prize so he lost interest in the contest and never returned the call. With Eckstein out of the way, the path was clear for Lauren Helmstetter, of Leawood, Kansas, to take the top spot with, “You’ll feel better when you see the doctor”—a fine example of transforming an ordinary statement into a joke.

Another annual contest challenged readers to create their own gag cartoon. Charles Barsotti drew the setup—a therapist taking notes next to an empty couch—and supplied eight potential patients (a squirrel, an anthropomorphic screwdriver, a king, a businessman, a woman, a dog, Superman, and a dragon) who could be cut out and placed on the couch. June Anderson and Dr. Alice McKay, of Henderson, Nevada, put the king there and created a sibling rivalry between him and the therapist: “Mom always liked you best.” Kip Conlon, of Brooklyn, New York, made Superman the patient and filled him with self-doubt: “Sometimes I think everybody’d be better off if I was a bird or a plane.” But Daniel Adkison, also of Brooklyn, took the prize by having the dog confess, “I can smell my own fear.”

Relatively few people, only about two thousand, submitted entries to the most challenging annual contest, which completely stumped me. It featured Frank Cotham’s drawing of two mechanics relaxing outside their garage while looking at a man who’s frantically waving at them from behind the wheel of a car that’s speeding round in tight circles. One of the mechanics is calmly commenting on the situation, and Michael Lewis made him philosophical: “I am reminded that the pleasures of life, like those of travel, lie in the journey rather than the arrival.” David Overman made him slightly more sensitive than his fellow mechanic: “Come on, just tell him you hear the noise.” But Jennifer Truelove, of Hoboken, New Jersey, won the contest by making him mildly curious: “At what point does this become our problem?”

On April 25, 2005, New Yorker editor David Remnick turned the contest into a weekly competition. Instead of picking a winning caption, the magazine selected three finalists and let the public choose the victor. The whole process, from printing the drawing to announcing the winning caption, took four weeks—one to submit entries, one to select finalists, one to vote on finalists, and one to count the votes. Here is the winning caption from the first weekly contest, which featured a cartoon by Mike Twohy:2

Roy Futterman, New York City

When Twohy’s cartoon appeared in The New Yorker as a captionless drawing, it took up the whole back page of the magazine. By the time it reappeared with Futterman’s winning caption,2 it shared space with two other cartoons at different stages of the judging process. One was a Jack Ziegler cartoon that had been featured as a captionless drawing two weeks earlier and now appeared above the three entries that had been selected as finalists. The other was a captionless cartoon by David Sipress. From that point on, every issue afforded readers an opportunity to enjoy or resent the winning caption in one contest, vote for their favorite finalist, and submit an entry for the current competition.

Choosing the Drawings

Like most drawings that appear in the contest, this one by Mankoff originally had a caption:

“Sorry, hard-ons, the ballbusters have it.”

That line didn’t make it past the censors, so Mankoff removed it and used the image for the contest. The winning entry then turned his drawing into one of the best single-panel cartoons I’ve seen:

“Well, then, it’s unanimous.”Anne Whiteside, San Francisco, Calif.

Sometimes a cartoonist will submit a captionless drawing to The New Yorker for inclusion in the contest. Robert Leighton did it only once:

“The drawing almost worked by itself,” he said, “but it would be funnier with a caption and since I knew there was nothing more I could add, I let it become someone else’s problem.” The winning entry, from Ken Park, of San Francisco, California, was a reference to daily crossword puzzles that get increasingly difficult as the week progresses: “Why couldn’t he have been murdered on a Monday?”

Leighton thinks the editors have, “for the most part, chosen wisely when they’ve decided to remove the caption from one of my cartoons and use the drawing for the contest.” But not always. Years ago he submitted this cartoon to The New Yorker:

“My next-door neighbor! And my next-door neighbor’s wife!”

It didn’t sell, so three years later he resubmitted the same drawing with a different caption: “My God! How long has this been going on?” The magazine removed the caption and used the image for the contest. The editors then selected the following three submissions as finalists, and the first two were nearly identical to Leighton’s original captions:

“How long has this been going on?”

Jeff Green, Brooklyn, N.Y.

“Oh, no! My best friend and my best friend’s wife!”

Mark Campos, Seattle, Wash.

“Interested in a threesome? I’ll just sit on the floor and sort tax receipts.”

Kathy Kinsner, New York City

To Leighton’s surprise, the third entry won the popular vote.

In a 2005 interview with Ben Greenman, an editor at The New Yorker, Mankoff explained that some drawings work better than others for the contest.1

Greenman: Let’s talk a bit about the images you’re picking. There are certain kinds of cartoons that wouldn’t work at all for this contest. There’s a famous New Yorker cartoon that you actually drew. The caption is “No, Thursday’s out. How about never—is never good for you?” But the image is just a man on a phone at a desk. It seems like that wouldn’t work.

Mankoff: It wouldn’t. People would just send in their generically funny man-on-phone lines, and we’d have no real standard for judging one against the other. Many would be funny in their own way, but there would be no competition between entries, no common ground, and, as a result, no contest. Now, if instead of the receiver he had a banana in his hand—

Greenman: Yes?

Mankoff: Well, maybe that wouldn’t be so good. But a banana at least puts us on the right road. You need some sort of incongruous element.

There was no incongruous element in Drew Dernavich’s drawing of two men stuck in a traffic jam, so it was particularly hard to caption:

Dernavich’s original caption was interesting—“What if traffic isn’t them, Martin. What if traffic is us?”—but I won the contest with something less philosophical: “Try honking again.”

Choosing the Finalists

It was initially the responsibility of Mankoff’s assistant to handle the first phase of judging each week’s contest by spending hours reviewing all five thousand to ten thousand entries and culling them down to the top fifty or so. Mankoff then picked the ten best, sent them to the magazine’s editors (who rated them “funny,” “somewhat funny,” or “not funny”), tabulated their responses, and selected three finalists from those that came out on top. The finalists used to get a call, but now they receive a congratulatory email that begins with the title of this book: “Your caption has been selected.” The contest is judged blindly, so the finalists’ identities are revealed only after their captions are chosen.

The assistants who reviewed or are still reviewing the contest entries deserve recognition: Andy Friedman, Marshall Hopkins, Zachary Kanin, Farley Katz, Adam Moerder, Jennifer Saura, Marc Philippe Eskenazi, Colin Stokes, and Rachel Perlman.

Andy Friedman is an artist and musician who worked for Mankoff when the caption contest was still an annual event, and his cartoons have appeared in The New Yorker since 1999. Initially they were published under the pseudonym “Larry Hat” because Friedman worried that people might take his art less seriously if they knew he was funny. His later work appeared under his own name:

“Recommend? No. But there are plenty of dishes this evening that I’d dare you to eat.”

Marshall Hopkins and Jen Saura have also had their cartoons published in The New Yorker:

Zachary Kanin, a former staff writer for Saturday Night Live and the co-creator of I Think You Should Leave with Tim Robinson,1 is a cartoonist whose drawings appear both in the magazine,

and in the caption contest:

Alexander Toth, Boston, Mass.

To survive the process of reviewing thousands of contest entries week after week, Kanin uploaded them into a spreadsheet, ordered them by length, eliminated all the jokes about the insurance company Geico (“There were always about five hundred submissions that were like, “Good news. Now you’re getting a better deal through Geico.”2), and ordered the remaining entries by common phrases so it was easier to spot the best version of the same joke. Still, he said, “I thought I was going to die.”3

Like Kanin, Farley Katz is a cartoonist whose work appears both in the magazine,

“Just in case the conference call runs long.”

and in the contest:

“Matisse now; Pollock later.”

Mark Laurent Asselin, Bethesda, Md.

I asked him how he feels when The New Yorker removes his caption from a cartoon and uses the drawing for the contest. “Hurt,” he said. “Then honored. Finally, aroused. Sorry, what was the question? Honestly, I’m always excited to see what great jokes people will come up with. I love seeing caption writers take my drawings to entirely new and unexpected places.” As for trying to caption a drawing in the contest that’s by another cartoonist, “I never click submit, but after years of reading thousands of entries I dream in captions and can’t help but write down a few ideas when I see the latest contest.”

Katz and the writer Simon Rich, who often contributes to The New Yorker, collaborated on The Married Kama Sutra: The World’s Least Erotic Sex Manual, and claim they collaborated on cartoons the magazine’s editors rejected. During an appearance on Running Late with Scott Rodowsky, they presented a few of their alleged submissions, including a cartoon that’s set in a restroom where two janitors are holding mops and high-fiving each other as they stand by a toilet. One janitor says, “Yeah—we are gonna clean the shit out of this thing.” According to Katz and Rich, that cartoon failed to appear in The New Yorker only because the editors did not understand how it worked on multiple levels. Other cartoons of theirs, they said, were so filthy they could reveal nothing but the captions: “That’s not yogurt,” “That’s not ice cream,” and “I’ve said it before and I will say it again—that’s a lot of feces.”

Adam Moerder contributed short pieces to the magazine, including reports from the annual New Yorker Festival. My favorite highlighted the difference between heroes and anti-heroes by providing several examples, including this one:

An oblong roll filled with various meats, cheeses, vegetables, spices, and sauces: Hero

Bread stuffed inside a slab of ham: Anti-hero4

Marc Philippe Eskenazi is a writer whose short humor pieces, including “Thank You for the Forty-Eight Cruise-Ship Brochures,” have appeared in The New Yorker. He’s also a musician, so Mankoff had him judge the magazine’s Caption Contest Song Contest.5 The winning entry came from Seth Wittner, of Henderson, Nevada, who set his song to the tune of Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “Proud Mary.” Here’s a sample lyric:

If you make us laugh, and you ain’t on our staff

Then you are in the runnin’ for a finalist’s place.

Eskenazi performed a rendition of Wittner’s song in a music video directed by Myles Kane,6 who went on to make “Voyeur,” the acclaimed documentary about motel owner Gerald Foos, who built an “observation deck” above his motel rooms so he could spy through ceiling vents on the guests below.

Eskenazi has also come up with ideas for New Yorker cartoonists Benjamin Schwartz and Liam Francis Walsh:

“Get A Tomb!”

Though he does draw, Eskenazi prefers to collaborate because he’s a better writer than artist. Here’s one of his cartoons:

His caption—“When”—appears very faintly at the top. Benjamin Schwartz liked the concept so he redrew the cartoon, turning the creature into an overcaffeinated man, and submitted it to The New Yorker. The magazine bought the drawing for the contest and subsequently chose the caption it had removed as one of the three finalists:

“Quick, before Bloomberg bans it!”

Rita Costanzo, Staten Island, N.Y.

“When.”

Victoria Rice, New York City

“Best decaf in town, Dolores.”

Krista Van Wart, Brooklyn, N.Y.

Rita Costanzo’s joke about Bloomberg won the popular vote, and the mayor, who once complained that no matter how hard he tried he could never make the finalists’ round in the caption contest,7 bought a print and hung it in his office.

Copyright © 2024 by Lawrence Wood