Introduction

Our mothers were the ashes and we were the light. Our mothers were the embers and we were the sparks. Our mothers were the flames and we were the blaze.

—EDWIDGE DANTICAT

I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe. Mama, I love you. Tell the kids I love them. I’m dead.

—GEORGE FLOYD

On February 14, 2019, my husband, Michael, and I were in Washington, D.C. We’d traveled there for the Frederick Douglass 200 Awards Gala, held in the Library of Congress. I remember feeling annoyed with myself that evening—in a rushed week filled with commitments, I’d packed an off-white dress to wear to the event. While there, I remembered that my monthly visitor was due and I excused myself to use the restroom several times throughout the night, paranoid I might find a red stain on the back of my dress. Each time, I breathed a sigh of relief and returned to my seat. Following the ceremony, I figured we would rest before our flight the next morning, but Michael had other plans. He surprised me with a dessert-and-wine reservation for Valentine’s Day.

Our ride dropped us off to enjoy the rest of the night. I ordered a deconstructed peanut-butter-and-jelly cheesecake that I excitedly waited to try. When it arrived and I took my first few bites, I suddenly felt sick to my stomach. I paused and sat back in my chair to take a breath. Then it occurred to me that my period wasn’t only due, it might actually be late. I was in my own world; I pulled out my phone to count my days again. The small possibility filled my mind with excitement—we’d recently decided to start trying for a baby. I was clearly distracted, and Michael asked what I was thinking about. I replied with a smile, “Let’s go to CVS.”

Long story shortened, that night, toward the last hours of Valentine’s Day, following an event honoring those carrying Frederick Douglass’s work forward, I held a positive pregnancy test in my hands. My heart filled with an indescribable feeling and my eyes watered as I showed the result to my life partner. A human being was developing inside of me. I was going to be a mother. I was going to bring a life into this world. Joy quickly started to vacillate with worry, the weight of the world falling on my shoulders. I wondered if up until that moment I’d been taking enough care of myself and my little one. I worried that I didn’t know enough about the steps I was supposed to take to make it through my pregnancy successfully. As if all the research I had done up until that point, as if all our conversations before deciding to try, had simply not been enough—a worry that so many feel. I was overjoyed, yes, but I was also instantly scared of losing my child. I prayed to God that we, my baby and I, would be protected.

I suppose this is an accurate and pithy description of motherhood, a lifelong wavering between utmost happiness and consuming worry. This might sound strange, but I was more grateful in that initial moment than I had ever been for the work that I do, especially for my Ph.D. I had just begun the second year of my doctoral studies at the University of Cambridge and was on my Leave to Work Away. This meant that the year was dedicated to my fieldwork and research, which happened to be on Black motherhood. I was grateful because my research, which led to this book, gave me examples of three incredible women and mothers who could guide me in the next stage of my life. In the journey of finding evidence of their lives, I was able to acknowledge the very real fears that come with motherhood, specifically Black motherhood, both during and after pregnancy, but I also found encouragement and a warm embrace to welcome me.

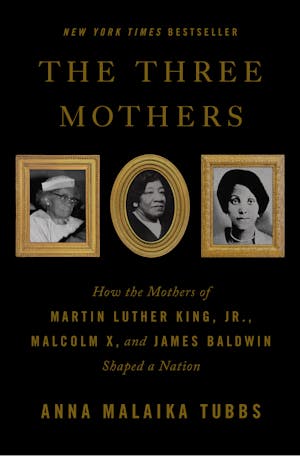

The three women I speak of are Alberta King, Berdis Baldwin, and Louise Little—women who have been almost entirely ignored throughout history. While this disregard of Black women’s contributions is widespread and so extensive that it is unquantifiable, the women I honor here have been ignored differently: ignored even though it should have been easy throughout history to see them, to at least wonder about them, and to think about them; ignored in ways that are blatantly obvious when the fame of their sons is considered. They were the mothers of Martin Luther King, Jr., James Baldwin, and Malcolm X, respectively. While the sons have been credited with the success of Black resistance, the progression of Black thought, and the survival of the Black community, the three mothers who birthed and reared them have been erased. This book fights that erasure.

Through the lives of the three mothers—Alberta, Berdis, and Louise—I honor Black motherhood as a whole and celebrate knowledge passed from generation to generation through the bodies and teachings of Black women. While we are all influenced by our mothers in one way or another, it is especially clear in these three instances just how influential each mother’s life experiences and teachings were on her son’s views and actions. Because of who Alberta, Berdis, and Louise were, Martin, James, and Malcolm were able to become the great leaders we all revere. Because of who Alberta, Berdis, and Louise were, the world was changed forever and it is time they receive their due credit.

In the book All the Women Are White, All the Blacks Are Men, But Some of Us Are Brave: Black Women’s Studies, editors Akasha (Gloria T.) Hull, Patricia Bell Scott, and Barbara Smith make a case for the significance of studying Black women in order to raise our collective consciousness. They highlight the crucial role an understanding of Black women’s lives can play in saving Black women’s lives. They write, “Merely to use the term ‘Black women’s studies’ is an act charged with political significance. At the very least, the combining of these words to name a discipline means taking the stance that Black women exist—and exist positively.…” My work is largely inspired by the guidelines found in But Some of Us Are Brave and specifically addresses the stance that “Black women exist—and exist positively.”

We must affirm Black women—a group that has historically been dehumanized—in humanizing ways. “Positively” does not mean that we should focus only on the positive facts about Black women’s lives; instead we must take in the whole picture, one that includes diverse perspectives, an acknowledgment of oppressive forces as well as an understanding of the ways in which Black women have survived such circumstances. Erasure, misrecognition, and historical amnesia have certainly contributed to the formation of our identity as Black women, but our fight against such forces with our affirmation and recognition of ourselves and each other has been much more telling. Through these practices we’ve created new possibilities that defy the limits placed upon us.

* * *

Writing about Black motherhood while becoming one gave me a much deeper perspective than I had before. As my own life and body transformed, it became even more important to me to tell Alberta’s, Berdis’s, and Louise’s stories before they became mothers. Their lives did not begin with motherhood; on the contrary, long before their sons were even thoughts in their minds, each woman had her own passions, dreams, and identity. Each woman was already living an incredible life that her children would one day follow. Their identities as young Black girls in Georgia, Grenada, and Maryland influenced the ways in which they would approach motherhood. Their exposure to racist and sexist violence from the moment they were born would inform the lessons they taught their children. Their intellect and creativity led to fostering such qualities in their homes. The relationships they witnessed in their parents and grandparents would inspire their own approaches to marriage and child-rearing. Highlighting their roles as mothers does not erase their identities as independent women. Instead, these identities informed their ability to raise independent children who would go on to inspire the world for years to come.

These women’s lives create a rich portrait of the nuances of Black motherhood. Yes, all three were mothers of sons who became internationally known, and their stories share many similarities, but by no means can their identities be reduced into one. Each woman carried different values, faiths, talents, and traumas. I hope their rich differences will open our eyes to the many influences and manifestations of Black motherhood in the United States and beyond.

The narratives of these three women have fueled and empowered me, but this work has been extremely difficult at times. Black motherhood in the United States is inextricable from a history of violence against Black people. American gynecology was built by torturing Black women and experimenting on their bodies to test procedures. J. Marion Sims, known as the father of American gynecology, developed his techniques by slicing open the vaginal tissues of enslaved women as they were held down by force. He refused to provide them with anesthesia. François Marie Prevost, who is credited with introducing C-sections in the United States, perfected his procedure by cutting into the abdomens of laboring women who were slaves. These women were treated like animals and their pain was ignored.

There is a paradoxical relationship between the dehumanization we Black women and our children face and our ability to resist it. Beyond the normal worries all mothers encounter as they progress through pregnancy and get closer to their labors, we Black mothers are aware that we are risking our lives. Black women in the United States are more likely to die while pregnant and while giving birth than other mothers. Beyond the normal fear that all mothers feel when the gut-wrenching thought of losing their child creeps its way into their minds, we Black mothers experience a heightened level of worry. We are aware of how differently our children are seen and treated in society, and our fears are confirmed by articles and news stories reporting the violence that Black children experience constantly, whether at parties, in school, or at their local parks. This fear continues as our children become adults who are in danger even as they sleep in their beds, sit in their own apartments, when they call for help, or when they go on a run.

Louise, Berdis, and Alberta were well aware of the dangers they and their children would be met with as Black people in the United States, and they all strove to equip their children not only to face the world but to change it. With the knowledge that they themselves were seen as “less than” and their children would be, too, the three mothers collected tools to thrive with the hopes of teaching their children how to do the same. They found ways to give life and to humanize themselves, their children, and, in turn, our entire community. As history tells us, all of their sons did indeed make a difference in this world, but they did so at a cost. In all three cases, the mothers’ worst fears became reality: each woman was alive to bury her son. It is an absolute injustice that far too many Black mothers today can say the same thing.

In the face of such tragedy, each mother persisted in her journey to leave this world a better place than when she entered it. Yet their lives continued largely to be ignored. When Malcolm X was assassinated, when Martin Luther King, Jr., was killed shortly after, and even when James Baldwin died from stomach cancer years later, their works were rightly celebrated, but virtually no one stopped to wonder about the grief their mothers were facing. Even more painful to me is the fact that their fathers were mentioned, while their mothers were largely erased.

I chose to focus on mothers of sons. Black men were certainly not the only leaders of the civil rights movement; mothers of revolutionary daughters have also been forgotten. I simply chose three figures who are often put in conversation together and who demonstrate the distressingly strong erasure of identity in the mother/son relationship. Coincidentally, I gave birth to a boy, my incredible little boy, and I have already faced others’ attempts to erase my influence on his identity. Phrases like “He’s strong, just like his father!” or “He’s already following in his dad’s footsteps” when he reaches a milestone cause more harm than people think. By choosing three mothers of sons, I do not want to erase daughters or other children. I am instead making the point that no matter our gender, everything starts with our birthing parent.

In telling the stories of these three mothers, I hope to join others who have responded to Brave’s call for “Black women to carry out autonomously defined investigations of self in a society which through racial, sexual, and class oppression systematically denies our existence.…” It is crucial to understand the layers of oppression Black women face, while remembering that solely studying oppression keeps us from honoring “the ways in which we have created and maintained our own intellectual traditions as Black women.” I pay close attention to this balance and bear witness to the many challenges Berdis, Alberta, and Louise faced while acknowledging their ability to survive, thrive, and build in spite of them.

Louise, Berdis, and Alberta were all born within six years of each other, and their famous sons were all born within five years of each other, which presents beautiful intersections in their lives. Because they were all born around the same time and gave birth to their famous sons around the same time, and two of them passed away around the same time, I reflect on Black womanhood in the early 1900s, Black motherhood in the 1920s, and their influence on the civil rights movement of the 1960s. The first of the three mothers was born in the late 1890s, and the last of the three passed in the late 1990s. Their lives give us three incredible perspectives on an entire century of American history. By seeing the United States develop through the lives of Berdis, Alberta, and Louise, you will be left with a richer understanding of each world war, the Great Depression, the Great Migration, the Harlem Renaissance, race riots, police brutality, welfare debates, the effects of policies proposed by each president they lived to witness, and much more.

But their stories go beyond a new understanding of American history, especially the civil rights movement of the 1960s. An ode to these three women is an ode to Black womanhood—perhaps Black women of today will also be able to find themselves in the life stories of Berdis, Alberta, and/or Louise, as I have.

When I first started this work, it quickly became apparent that without knowledge of the stories of these three women, the world was missing an enormous piece of our understanding of Black resistance in the United States. The fascinating facts I have been able to uncover provide incredible new depth for our appreciation of Black American history, but this research is about far more. The women’s lives offer invaluable new knowledge about the context of the past, how the storyteller influences the story, and how reevaluations guide our contemporary understanding of individuals, communities, and society. This kind of writing becomes even more needed and holds even more power when thinking about groups who have historically been erased and misrepresented, groups who have been kept from telling our side, groups who suffer the repercussions of such exclusion to this day, and groups who continue to resist all of this.

In my desire to better understand the circumstances of the lives of Louise, Berdis, and Alberta, I have called upon the work of Black feminists in the fields of sociology, history, and political science and others outside the academy. Interwoven with their life stories and historical context, you will also find an engagement with Black feminist analysis relating specifically to dehumanization, resistance, and motherhood. Black women have been, and continue to be, treated as less than human, so it’s crucial to break down the terms I will be using to discuss this going forward.

Dehumanization takes various forms. People are treated as less than human when their basic rights are not granted/respected, when their agency is taken away, when they are objectified through language and actions, when violence is used against them, and when they are expected to remain silent despite these circumstances. All three mothers experienced this throughout their lives. Audre Lorde—one of the most renowned poets, essayists, and activists in history—writes about the reason dehumanization happens in the introduction to her essay “Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference”:

Much of Western European history conditions us to see human differences in simplistic opposition to each other: dominate/subordinate, good/bad, up/down, superior/inferior. In a society where the good is defined in terms of profit rather than in terms of human need, there must always be some group of people who, through systematized oppression, can be made to feel surplus, to occupy the place of the dehumanized inferior.… Institutionalized rejection of difference is an absolute necessity in a profit economy which needs outsiders as surplus people.

Lorde shows that dehumanization is a component of any society that views capital as more important than humanity and as something that affects and implicates all members of such a society. However, each member is inherently treated differently depending on levels of disadvantage.

As you read about Alberta, Berdis, and Louise, keep Lorde’s words in mind. In order to understand their beliefs and their actions, we must know the extent to which their humanity was denied. This denial stemmed from times of slavery and continued in both obvious and discreet forms from their birth until the day each died. In the same essay, Lorde continues, “Unless one lives and loves in the trenches it is difficult to remember that the war against dehumanization is ceaseless. But Black women and our children know the fabric of our lives is stitched with violence and with hatred, that there is no rest.” At each stage of the three mothers’ lives, we witness their knowledge of this unfortunate truth and their need to resist.

By “resist,” I am talking about the ways in which Berdis, Louise, and Alberta pushed against dehumanization, refusing to acquiesce to the notion of their supposed inferiority. Resistance, like dehumanization, takes place in many forms; I see it as any action taken to assert Black humanity. Martin Luther King, Jr., James Baldwin, and Malcolm X are known for their resistance, and in this book you will see how the three women’s teachings, through both words and actions, translated directly into their sons’ writings, speeches, and protests. These men became symbols of resistance by following their mothers’ leads.

Even after death, Berdis, Louise, and Alberta continue to face a denial of their humanity when they are either erased or misrecognized. Up until this book, portrayals of the three mothers have been mostly limited or completely inaccurate. The three women have been hidden not only behind their sons but also behind their husbands. And in the rare moments when the mothers are mentioned, they are often presented as footnotes that are out of context. This in and of itself is wrong, and it contributes to the inhumane treatment of Black women as a whole. I do not blame the sons or the husbands for such erasure, I blame a society that devalues women and mothers, especially women and mothers of color. In Eloquent Rage: A Black Feminist Discovers Her Superpower, Brittney Cooper, associate professor in the Department of Africana Studies/Women’s and Gender Studies at Rutgers University, writes, “Recognition is a human need, and there is something fundamentally violent about a world that denies Black women recognition on a regular basis.” This book acts as a site of resistance to the dehumanization Berdis, Louise, and Alberta continue to face posthumously and to the dehumanization Black women and mothers face all over our country today.

In her book Sister Citizen: Shame, Stereotypes, and Black Women in America, Melissa V. Harris-Perry talks about Black women living in a “crooked room,” referencing a cognitive psychology experiment where participants were placed in a crooked chair in a crooked room and asked to straighten themselves vertically. Surprisingly, individuals who were tilted as much as thirty-five degrees reported that they were sitting completely straight so long as they were aligned with other objects and images in the room that were at the same angle. Harris-Perry uses the symbol to discuss the circumstance Black women find themselves in. The other objects and images in the room that try to keep Black women from standing tall speak to the many strategies in place to dehumanize Black women by erasing and misrepresenting them. Harris-Perry writes: “When they confront race and gender stereotypes, black women are standing in a crooked room, and they have to figure out which way is up. Bombarded with warped images of their humanity,… [Black women can find it] hard to stand up straight in a crooked room.”

In this book, I write about the circumstances contributing to the crooked rooms that Berdis, Louise, and Alberta inhabited and how the rooms developed and changed throughout their lives. More important, I think of the ways each woman found to get out of the crooked chair she was forced to live on and continue to stand with her head held high. I also think of the ways they started to change the room to fit their own view of themselves, their children, and their community. Reading this book, knowing the names Alberta King, Berdis Baldwin, and Louise Little, and sharing what you learn with others are all acts that help to straighten the room for Black women today.

I have pieced these stories together from several different sources. I read and watched many of the works of Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, and James Baldwin—books, speeches, letters, interviews—and pulled out the places where they mentioned their mothers or where a character was based on their moms. I also spoke to scholars who studied the sons and read the books they and others had written. If any family members had written or spoken about their experiences, I read those books and transcripts as well. I spent hours scanning letters and documents from the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, the National Museum of African American History and Culture, the Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute at Stanford University, and the King Center in Atlanta. While the three mothers have mostly been ignored by scholars, in Louise’s case, I was extremely fortunate to have examples of extensive research from the late novelist Jan Carew, as well as a recent study from Professor Erik S. McDuffie of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. With their work on Louise as inspiration, I reached out and spoke to family members of the three women who were willing to speak with me. I have also spoken to local historians and gained access to birth and death certificates with their help. I’ve used what I could find in census data, although this information was limited.

All of these women could have several books written about their lives, just as their sons have, so I don’t claim to have captured everything here. But I am proud of how much I’ve been able to find. It’s also true that with any biographical work it can be difficult to know what is and is not factual, especially when you write about people society has not deemed “important.” One source claims that Louise was born in 1894 and another shows she was born in 1897; a family member says that Berdis was born in 1903, but her own mother’s death certificate reads 1902 and Berdis’s name never appears on any census; a scholar can claim that Alberta was quiet, while a friend of the family describes her as lively. All this to say it’s impossible to know what is “true” if you weren’t the one who lived it, and there are many layers to the truth, depending on your perspective. This book, like all history, is composed of many sources that might contradict one another in small ways, but it still holds truth about the significance and influence of each of these mothers and speaks to their legacy.

When I began writing this book, I wondered what it would be like if I could sit down with Berdis, Louise, and Alberta. I wondered what they were like before they became mothers, what their dreams were, what they cared about, whom they were friends with. I wondered what I would look for if I could follow them for a few days, if I could learn what inspired them and what scared them. I thought to myself, If I could sit down with these three mothers, what would I ask them? I realized I would want to know how they pushed themselves to keep going even when various factors tried to stop them in their tracks: how Louise held on to her courage even when her husband was killed; how Berdis stood up to her husband even when he was abusive; how Alberta saw hope even after her sons died. I would want to know what advice they would give us after witnessing some of the most transformative moments in American history and after seeing progress come and go. In the absence of being able to speak with them directly, I am consoled by my ability to study them, write about them, and share their stories. It is time that the world knows their names.

In Alice Walker’s book and essay of the same name, In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens, she writes:

Our mothers and grandmothers, some of them: moving to music not yet written. And they waited. They waited for a day when the unknown thing that was in them would be made known; but guessed somehow in their darkness, that on the day of their revelation they would be long dead.… But this is not the end of the story, for all the young women—our mothers and grandmothers, ourselves—have not perished in the wilderness. And if we ask ourselves why, and search for and find the answer, we will know beyond all efforts to erase it from our minds, just exactly who, and of what, we black American women are.

With Walker’s words in mind, I hope to bring more Black women’s stories out of the darkness and into the light, to find the clues laid out for me by women who possessed their own dreams and talents, to revisit our current accounts and reread them with Black women’s lives at the forefront, and to better know who, and of what, we Black women are. By paying tribute to Louise, Alberta, and Berdis, by recognizing who they were, I believe I have a better understanding of who we as Black women are today. I hope you will feel the same way.

Copyright © 2021 by Anna Malaika Tubbs