1The Origins of Cage

To understand Nicolas Cage, you first have to understand Nicolas Coppola. And to understand Nicolas Coppola, you first have to know a bit about the Coppola family, which, since arriving in America from Italy at the turn of the century, has produced multiple generations of artists whose lofty ambitions have collided, sometimes violently, with the commercial expectations and financial realities of the country that welcomed them. And while it might be easy to dwell on the Coppola side of the family, with its rich history and famous members, it’s best to keep going. The Coppola name loomed large over Nicolas Cage’s childhood and young adulthood—so large that he felt the need to shed it before he could move on. But his early days were defined just as much by his mother—sometimes by her presence, sometimes by her absence.

Family may not be destiny, but recurring patterns can be tough to ignore, particularly when they take the form of irrepressible artistic instincts. Cage’s great-grandfather Francesco Pennino, a first-generation Italian immigrant, played music, wrote songs, helped import Italian films to the United States, and even served as Enrico Caruso’s pianist. Another great-grandfather, Augustino Coppola, produced two musician sons, Anton and Carmine. Carmine Coppola, Cage’s grandfather, played flute, a talent that earned him a scholarship to Juilliard and brought the family to Detroit for a job with the Detroit Symphony that included work for the Ford Sunday Evening Hour. In 1939, the show’s corporate sponsor would provide a middle name for one of Carmine’s sons, Francis.

Francis Ford Coppola wasn’t the first child born to Carmine and Italia Coppola, however. He was preceded by five years by his older brother, August, born in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1934. To August, Francis would become both sidekick and acolyte.

“As a younger man, the words I’d use of Augie are a purity, and a kindness,” Francis told biographer Peter Cowie. “A lot of brothers would dump a kid five years younger, but he would always take me everywhere. At one point we even lived in the same room, and you’d think he’d be dying to get rid of me even more. I was very charmed by him and very much wanted to imitate him.” With their sister, Talia, who’d follow Francis in 1946, the Coppola boys lived a peripatetic existence, moving from one New York neighborhood to another as Carmine’s jobs changed and his fortunes rose and fell.

A gifted but less-than-dedicated student, August would frequently skip school to take Francis to the movies, where they took in everything, from Disney films to Abbott and Costello comedies. August’s mentorship didn’t stop with movies. He’d later introduce his younger brother to other forms of art and literature as August developed into a talented writer. August also became something of a local legend, described by Francis years later as “the hero in the neighborhood … the one the girls liked and the other fellows were afraid of.” The relationship proved central to Francis’s development, and intense fraternal relationships would find their way into many of his films.

In these early days, August always seemed a few steps ahead of his younger brother, including in his choice to trade the East Coast for the West. August earned a philosophy degree from UCLA; returned to New York by way of Hofstra, where he picked up a master’s degree in English; then went west again, earning a doctorate in comparative literature via an unusual program designed—as the author bio for his sole published novel, The Intimacy, notes—“for Renaissance men and women” that involved work at Occidental, Claremont, Whittier, Redlands, and Pomona. (That it was sponsored by the Ford Foundation seems like another cosmic coincidence. It wouldn’t be the last such coincidence to play a role in Nicolas Cage’s origin story.) Upon graduation, August took a job teaching comparative literature at Cal State Long Beach.

It was in Los Angeles that August met dancer and choreographer Joy Vogelsang, who, like August, had roots in another part of the country. The daughter of Bob and Louise “Divi” Vogelsang, Joy had moved with her family to Los Angeles from Chicago, where they’d run a grocery on the city’s South Side. In LA, they’d picked up where they’d left off, opening a market on Melrose Avenue. Bob and Louise purchased a home in Hollywood, where Louise would remain for more than sixty years, continuing to call it home after Bob’s 1988 death until shortly before her own death in 2010, at the age of ninety-five. Cage would be a frequent visitor, and sometime resident, during his childhood and through the early days of his career. Occasionally, he’d need a place to which he could escape.

* * *

Nicolas Kim Coppola was born on January 7, 1964. The third son of August and Joy, he followed his brothers, Marc (born in 1958) and Christopher (born in 1962). Theirs was not always a settled home. Early in Cage’s career, he’d say little about his family. As time passed, he revealed more about an upbringing troubled by his mother’s struggles with mental illness. Joy first entered an institution in 1970, when Cage was six. “She would go away for years at a time,” he told the New York Times in 1994. “When she got too erratic, she went to the—she went away. Then my childhood consisted of going to see her. And that hallway was a long hallway, let me tell you, going in there with the crazy people who would be touching and—it was very arresting.”

Cage responded in part by retreating into a fantasy world, looking first to television as a way out. “I was six years old. I was sitting on the living room carpet watching our old round, oval-shaped Zenith TV,” he told NPR’s Terry Gross in 2002, “and I just remember, I wanted to be inside that TV so bad. I just wanted to get out of there and get in that TV. And I think that’s my first real cognizant recollection of wanting to act.” (The particular Zenith he remembered seems to have belonged to his grandmother Louise. Years later, he’d ask her for it and install it in one of his homes.) Yet even as he tried to retreat from the world and his mother’s condition, they became a part of him.

“It obviously, when I look at some of the characters, impacted the work,” he told Rolling Stone in 1995. “If it wasn’t for her, I don’t think I would have been able to act. I was just lucky that whatever was looking out for me gave me the ability to be a catalyst and to convert it into something productive.” That future use didn’t assuage fears of inheriting his mother’s condition. “I used to freak out that it was going to happen to me,” he said, “but everybody who I asked about it said that if it was going to happen, it would have happened when you were in your teens.”

In interviews, Cage sometimes recalls happy memories of making plays, sketches, radio shows, and Super 8 movies with older brothers Marc (who’d become an actor and radio personality) and Christopher (who’d become a director and producer). These would prove to be formative experiences, as would his father’s cultural education, a habit August carried over from his childhood with Francis. Guided by August, Cage watched Fellini and Kurosawa films as a preteen. “When I was a kid, the other kids were seeing Disney, and he was showing us movies like Fellini’s Juliet of the Spirits,” Cage would later tell Playboy’s David Sheff. Jean Marais’s rumbly, leonine work in Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast made a deep impression, as did films from the German Expressionist school, like Nosferatu, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, and The Golem, for both their atmosphere and their stars’ performance style, which often sought to channel extreme emotion through gestures and facial contortions that held nothing back.

In early interviews, Cage often mentioned a more dramatic childhood incident: his expulsion from school at the age of ten for a prank in which he brought egg salad sandwiches to school after lacing them with fried grasshoppers. This landed him in what he describes as a school for juvenile delinquents. After being bullied by a trio of older kids, he decided to take matters into his own hands. “One day,” he told the LA Times’s Michael Wilmington in a 1990 profile, “I went home and I’d had enough. I disguised myself as this character—you know, chewing gum, wearing sunglasses, cowboy boots—and I got on the bus and said, ‘Yeah, I’m Roy Richards, Nicky Coppola’s cousin, and if you screw with him again, I’m gonna kick your ass!’ They bought it. That was really my first experience in acting.”

Cage’s parents divorced in 1976, when he was twelve. By fifteen, he knew he wanted to act, inspired in particular by James Dean’s work in East of Eden. In that inspiration he’s hardly alone among young actors, but Cage has also mentioned performers as far afield as Jerry Lewis and Bill Bixby—the latter the mild-mannered star of The Courtship of Eddie’s Father, My Favorite Martian, and The Incredible Hulk (in which Bixby played the Hulk’s meek alter ego)—as influential favorites. But wanting to act is one thing, and making it happen is another, and Cage would encounter distractions and obstacles along the way. One such distraction involved moving in with one of the titans of 1970s filmmaking, his uncle Francis, as a high school freshman while his father traveled. And it’s here, at Francis’s Napa Valley home, miles away from Los Angeles, that the story of Nicolas Cage first hit the ever-changing tides of Hollywood filmmaking.

* * *

There’s a simple, two-part story about what happened in Hollywood between 1969 and the early ’80s, one that makes Francis Ford Coppola a hero in the first half and a victim in the second. It goes like this …

By the end of the 1960s, Hollywood had started to spin its wheels, releasing flop after flop that failed to lure moviegoers to the theaters, especially younger moviegoers. Enter Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider, an innovative road movie that became a runaway hit and constituted a shot across the bow to the Hollywood Old Guard that a new generation of filmmakers had arrived. From film schools like NYU, USC, and UCLA (Coppola’s alma mater), a generation of movie-mad filmmakers steeped in the influence of Bergman, Kurosawa, and the French New Wave and informed by the break-the-rules sensibility of the counterculture began to remake Hollywood in their own image. Coppola found great success in this environment, penning the Academy Award–winning screenplay to the 1970 film Patton and releasing a string of unimpeachable masterpieces: The Godfather in 1972, both The Conversation and The Godfather: Part II in 1974, and Apocalypse Now in 1979. He thrived in the world he helped create.

In the middle of the 1970s, however, that world had started to fall apart thanks to greed and changing tastes. Steven Spielberg’s Jaws created the modern summer blockbuster, and studios’ goals shifted from turning a profit by way of many small and medium-size films to making a lot of money with fewer bigger, and inevitably less personal, productions. George Lucas’s Star Wars confirmed the wisdom of this approach. Soon, quirk and character gave way to space epics and sequel after sequel. What’s more, some of the era’s best and brightest spent too much money on movies no one wanted to see, like Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate and Coppola’s One from the Heart. If New Hollywood can be said to have begun with the premiere of Easy Rider in the summer of ’69, then One from the Heart’s less-than-rapturously received Radio City Music Hall premiere in January 1982 serves as convenient end point.

Though true in broad strokes, this version of the story leaves out some important details, Coppola’s role not least among them. In truth, Coppola’s first attempt to find a new, more personal way of making movies virtually collapsed before the decade had even begun. In August 1969, he released The Rain People, an unusual road movie he made on his own terms that earned strong reviews but never found an audience. In December he founded American Zoetrope, a still-active, if much-changed, production company based in San Francisco, in an attempt to put some symbolically significant and practically useful miles between himself and Hollywood.

But it was Hollywood that still paid the bills, and less than two years into its existence, American Zoetrope experienced the first of many existential threats. In 1971, its first feature, THX 1138, directed by Coppola’s close friend, and American Zoetrope vice president, George Lucas, met with a frosty critical reception and commercial indifference. Its failure led Warner Bros., whose meager investment in American Zoetrope had helped keep it afloat, to sever ties, bringing in-the-works projects to a halt. These included what would have been the debut film of Black Stallion director Carroll Ballard, Coppola’s The Conversation, and an unusual project entitled Apocalypse Now—an adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, written by John Milius and originally envisioned as a project for Lucas to shoot documentary style with 16 mm cameras. Coppola made The Godfather, his first masterpiece, out of economic necessity, reluctantly agreeing to adapt Mario Puzo’s lurid best seller while lamenting to his father that Paramount wanted him to direct a “hunk of trash.”

Out of a work-for-hire job adapting a much-read potboiler for famously temperamental producer Robert Evans, Coppola made one of the landmark films of the 1970s. The Godfather—which went on to win an Academy Award for Best Picture, Best Actor, and Best Adapted Screenplay—didn’t begin as a distinctive artistic statement. Coppola wrestled with it until it became one. Between its even-better sequel, Coppola sandwiched the smaller, thornier classic The Conversation, becoming, in the process, the first director to see two films nominated for Best Picture in the same year. The Godfather: Part II walked away with the prize, earning Coppola awards for Best Director and, with Puzo, Best Adapted Screenplay. Also picking up Oscars: Robert De Niro, for Best Supporting Actor (his first), and a Dean Tavoularis–led team for Best Art Direction. This wasn’t the independent future Coppola envisioned for himself and those around him when he founded American Zoetrope, but he was making it work anyway.

Success brought money, but Coppola was never good at holding on to money. He poured it, along with his energy, into American Zoetrope, particularly the newly revived Apocalypse Now, a film he now planned to direct and whose agonizing production could easily have ended the company (to say nothing of Coppola’s career, marriage, and possibly life). Though some speculated that the film would never see completion, as its release date changed first by months and then years, Coppola pulled it off, to tremendous acclaim and surprising financial success.

Then, either his luck ran out, hubris caught up with him, audiences abandoned him for shinier projects, or some combination of the above took place. Determined to make an old-fashioned film using cutting-edge technology—and to work on soundstages after the dangerous location shooting of Apocalypse Now—Coppola created expensive, elaborate sets for the bittersweet musical One from the Heart while directing the action from inside a trailer filled with fresh-from-the-factory video equipment. As his vision expanded, so did American Zoetrope’s debt, one intensified by the underperformance of projects like Hammett (directed by Wim Wenders) and The Escape Artist (directed by another longtime Coppola associate, cinematographer Caleb Deschanel). In 1983, Coppola would declare bankruptcy and then spend the rest of the ’80s attempting to eliminate that debt, sometimes making payments of over a million dollars per week as he took on jobs he would have eschewed just a few years earlier.

Coppola’s story both confirms the accepted New Hollywood narrative and complicates it. His career illustrates that a trend can be true on a macro level but made fuzzy by individual examples. Coppola was part of a wave of 1970s auteurs who thrived in that decade’s more relaxed, less risk-averse atmosphere, and in some ways his path mirrors that of Robert Altman, Hal Ashby, Cimino, Peter Bogdanovich, Michael Ritchie, and others. Yet American Zoetrope nearly collapsed in the early 1970s, at the height of the film industry’s supposed openness to daring new filmmakers. Coppola and his peers found success within the Hollywood system, but even before the success of Jaws, signs abounded that the changes they introduced wouldn’t last. In 1974, the year Coppola earned two Best Picture Oscar nominations, the top-grossing films included studio disaster movies like The Towering Inferno, Earthquake, Airport 1975, and The Trial of Billy Jack, The Life and Times of Grizzly Adams, and Benji, a mix of oversize Hollywood productions and independent films that no one would mistake for the work of paradigm-shifting visionaries.

Coppola, for his part, took on the role of paradigm-shifting visionary as a burden and tried to carry it as far as he could. At its height, American Zoetrope’s empire included an LA studio, multiple production facilities, a magazine, a traditional theater, a radio station, and a production and distribution wing whose output included original projects and films by Coppola idols like Akira Kurosawa and Jean-Luc Godard. Coppola’s undoing came less because he tried to separate from Hollywood and more from his attempt to become his own Hollywood. With One from the Heart, he even tried to tap into the spirit of classic Hollywood using new techniques. The film’s out-of-control costs had little to do with its modest story and much to do with its grandiose scale and Coppola’s commitment to pursuing a lifelong interest in cutting-edge technology.

Even as this dream fell apart, however, New Hollywood’s grasp on the movie world didn’t loosen all at once. Lucas helped spread the studios’ mania for blockbuster-size hits, but Star Wars remained the result of an independent-spirited filmmaker pushing hard for a vision that nobody else could see and a film that (at first, at least) nobody wanted to make—and one inspired in part by the images of American military might clashing with the Vietcong. Lucas didn’t so much abandon the Zoetrope dream with Star Wars as repackage it. And the moviegoing public’s taste for the thornier, more intimate filmmaking that helped define the decade didn’t dissipate at the first sight of Darth Vader. The top-grossing film of 1979, two years after Star Wars, wasn’t Rocky II or Alien, but Kramer vs. Kramer.

In the end, Coppola built a kingdom on a foundation of sand, one shored only temporarily by the miraculous success of Apocalypse Now. But while it lasted, it still felt like an empire, one at its height when Coppola welcomed Nicolas Cage into his home for a year.

* * *

In the years after August and Joy’s divorce, both Marc and Christopher grew old enough to move out of their father’s house, leaving only Nicolas behind. Early in Cage’s high school career, August told his son he’d be spending the next year in Napa Valley with his uncle Francis and aunt Eleanor. The move would produce unintended consequences, removing Cage from what had become a comfortable environment in LA and sending his grades plummeting.

“I was in ninth grade, getting straight A’s, really excited about school,” Cage told the New York Times in 1994. “Then I was put into this little country school. I went suddenly from being the cool guy to the geek. My grades went from straight A’s to straight F’s.” He also found himself exposed to wealth of the sort he’d never experienced back in Long Beach.

Cage was presumably unaware that, at the time, United Artists had only recently considered repossessing Coppola’s property and evicting his family from their home to recoup the company’s investment in Apocalypse Now, and he couldn’t foresee the money troubles that would dog Francis in the years to come. But he could see what he didn’t have, and despite describing living in “a wonderful house with wonderfully generous people,” he found himself overwhelmed with envy, drawing parallels between his situation and that of the orphan Heathcliff in Wuthering Heights, telling himself, “I am going to get even somehow.” Later, he’d reflect that it was “sort of unfortunate that it was revenge that fueled much of my ambition.”

This didn’t interfere with his plans to pursue that ambition as far as it would take him, even if he’d yet to discover a channel for it. He’d soon find one, however. Cage’s time in Northern California also brought him to San Francisco’s American Conservatory Theater, which had already served as a training ground for Danny Glover and would later produce alums including Annette Bening, Anna Deavere Smith, and Chris Pine. Beyond high school productions, this would be the extent of Cage’s formal acting training.

But Beverly Hills High, to which he returned after his time with Francis’s family, offered advantages unavailable at other schools. Among them, acting teacher John Ingle, who’d find steady, high-profile work after his retirement from the school in 1985 thanks to his supporting turns in films like True Stories and Heathers and a nine-year run on TV’s General Hospital. If a teacher’s achievements can be measured by his students’ accomplishments, then Ingle’s are considerable; his former students include Albert Brooks, Richard Dreyfuss, Barbara Hershey, David Schwimmer, and Crispin Glover, a friend of Cage’s who’d soon costar in his first paying job.

* * *

By 1981, the cameras beckoned. Now seventeen, Cage, who’d grown up making 8 mm films with his brothers, appeared in the Super 8 short The Sniper, directed by a classmate. His other project, the ABC-TV pilot The Best of Times, reached a wider audience. A hybrid of sitcom, sketch show, and after-school special, it was executive-produced by George Schlatter, who’d enjoyed great success with Laugh-In in the late 1960s and early ’70s and had launched the hit human interest show Real People in 1979. Laugh-In had connected with audiences by repackaging the era’s youth culture in a format safe for mainstream audiences. The Best of Times plays like a similar attempt to tap into the interests of early ’80s kids drawn to video games and New Wave music.

Billed as a show in which “seven energetic teenage performers express their views on parents, peers and politics through song, dance and comedic vignettes,” the Best of Times pilot yielded strange, though sometimes charming, results. Crispin Glover stars as a normal, everyday teen—it’s pretty much the last time the famously eccentric actor would play it straight—who serves as the central figure in a group of kids cast to represent different types: the nerd, the popular girl, etc. (Jackie Mason rounds out the cast as an easily annoyed convenience store owner, the only adult with a significant role.) As “Nicolas”—the show’s conceit had the cast sharing first names with their characters—Cage plays the resident jock, a Stallone-worshipping, usually shirtless beach rat who spends most of his time lifting weights (when not dancing in overalls during a car wash musical sequence set to the recent Dolly Parton hit “9 to 5”).

It’s a window into how Cage’s career might have gone. Towering over the rest of the cast and already appearing too mature for high school, he could look the part of a dumb jock and might easily have gotten slotted into such roles. To the show’s credit, The Best of Times does give him a chance to show off some dramatic chops, via a monologue in which his character worries about global tensions and his future. The script could never be mistaken for Eugene O’Neill (“I just hope we don’t have a war! It’d kind of spoil things, you know what I mean?”), but Cage sells it.

Writer Carol Hatfield recalls the teenage Cage as being “very cute.” “He had a ton of energy and a lot of ambition,” she says. “When the auditions were held, he ran from his high school to Beverly Boulevard, where George’s studios were located.… [W]e knew right away that he was destined for greatness.” The pilot drew mixed reviews when it aired in July. In the Sacramento Bee, critic Dean Huber called it a “teenage world in wild caricature,” but the New York Daily News’s Kay Gardella dubbed it “a blessed relief from specials about teenagers on drugs.” There would be no further installments, however. “I would have been surprised if it was picked up,” Hatfield says. “It looked pretty cute when I saw it recently. But at the time, the writers were disappointed, to say the least.”

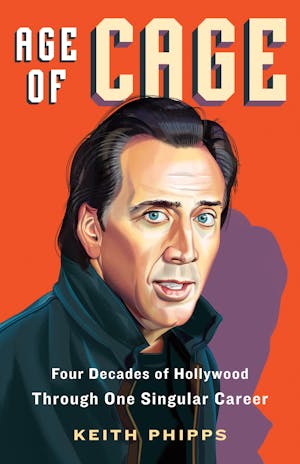

Copyright © 2022 by Keith Phipps