ONE

I’M PAID TO BELIEVE IN what I can see.

Okay, I don’t actually get paid, pero it’s the principle of the thing, entiendes? Anyway, all I’m trying to say is that I’m mad observant—it’s kinda my thing.

Pero that place I saw last week was nuts. Straight tontería, you feel me? I was just trying to finish my movie, inform the masses, and maybe score some extra credit to start off the eighth grade … but now? Everything is upside down. And I mean that last part literally.

Wait. I’m doing that thing that I hate in other people’s films—starting in the middle. So, let’s rewind and run the whole thing back.

It was all good just a week ago. I woke up in my usual bed in the house with yellow walls and a blue fence on Talman Avenue. Now, I’m saying blue fence because it’s been passably CTA blue my whole life, but it hasn’t ever been all the way blue. Ever since I can remember, we’ve lived here, behind this chain-link fence with peeling paint that Mami always means to repaint but never actually does. Even when I was super little it had tiny nicks and cuts in it from where mi hermana, Lorena, would jump over it to ride bikes down the block. Or, from the dents we made playing baseball.

All my life, through this fence, I’ve been watching people from the block ride down the street. People like our neighbor Manuel, driving by between his gigs playing guitar with a bachata band and his job making lightbulbs at the local factory. According to Mami, our family and Manuel must be the only Dominicans in all of Chicago. Most folks here are Latinx—that’s the gender-neutral version Lorena learned in college. I like the word, and it’s pretty easy to say once you get the hang of it. But most people here are Mexican or Puerto Rican like my best friend, Celeste.

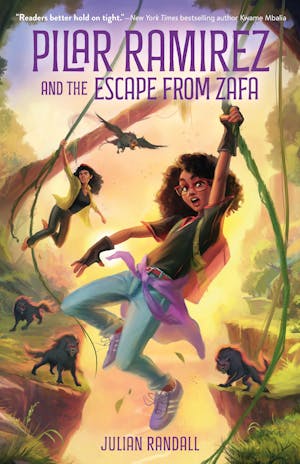

That reminds me, my name is Pilar Violeta Ramirez—that’s Pee-LAR—say it right or don’t say it at all, entiendes? For twelve years straight everybody and their mom, even their cousins, have been mispronouncing my name. As a result, the vice principal of my grammar school told Mami I have “patience issues.” Which is slander. I’m super patient—a good director has to be. I’m just not patient with people who think my family would ever name a lil’ Dominican girl “Pillar” and send her out into the world. Because when I say it that way, it doesn’t make any sense, right?

Speaking of things not making sense, let me bring it back to the day my whole life changed. I woke up one morning in Chicago and went to sleep that night on a magic island.

That morning, my best friend, Celeste, wasn’t around. Her family had moved to Milwaukee because the rent in Chicago had been going up and up since I was a baby. Most of the people I’d grown up with were gone. Some live in cheaper parts of the city, some got new jobs in another state … but no matter the start of the story, the end is the same: They ain’t here no more.

It feels like the music has been leaking out of our block a bit more each month with each dweeby-looking white kid who moves into the buildings that used to be Marcelo’s crib or Vanessa Martinez’s apartment. Developers even tore down the old factory—the one where Lorena hit her first home run on the roof (which was super cool, even for her)—to build a medical insurance building (boring, no character, no story at all).

It’s basically just us now, me and Abuela and Mami, bracing behind our shabby old blue fence, facing new building after new building. Under their breath, the invaders say we’re the immigrants. Pero as long as I’ve known what home is, we’ve been right here. They’re colonizers who use credit cards to put their name on things they don’t even understand. One day the colonizers are going to be the subject of my next documentary—them and the America they built on top of mine.

That morning there wasn’t any music and there wasn’t any Celeste, but I had a job to do and I was gonna do it. You see, Abuela brought Mami over from Santo Domingo, the capital of the Dominican Republic, back in 1957, when this real slimeball, Trujillo, ran the whole island. We don’t really talk about him in history class, but that dude was a special kind of evil. Murder, torture, genocide on Haiti, and violence against women that makes Mami and Abuela flinch when they talk about it. You name a bad thing and Trujillo and his goons were up to their eyeballs in it.

Abuela lived through twenty-five years of that porque she’s basically a superhero. She can go almost invisible when she wants to, stay real quiet and wait for the right moment to strike. She’s where I get my patience from on the real. When I’m waiting for the perfect shot to enter my lens, I try to be like her, as observant as possible. The city is never fully quiet, but sometimes I can be and that’s when I do my best work.

One day back on the island, Abuela got her last warning shot that it was absolutely, without a doubt time to bounce from the Dominican Republic. The details were sketchy, because nobody liked to talk about them, but after I interviewed a bunch of people for the documentary I’m filming (working title: ¿Dónde está la virgen de la trujillato? copyright pending), a couple of facts started to line up.

The story goes that Mami had a cousin named Natasha and they were closer than sisters. Natasha’s mom had been jailed for “stoking insurrection,” which basically meant she wanted to be free. Trujillo and his goons weren’t about to let that happen, so they made her disappear. Natasha then moved in with Mami and Abuela in a little house while they waited for Trujillo to die, hoping the world would right itself.

But when both cousins were thirteen or so, Natasha just vanished. No warning, no warrant, no scary men at the door, no arrest. She just went out to get groceries one day y se fue. Vanished into thin air. The more I researched, the more I learned that apparently this happened all the time back in the day. Trujillo didn’t mess with you, y ya. You were gone and just like that, people stopped mentioning you. Like being gone was contagious.

Abuela ain’t need no further warning. She dried her tears, snapped Mami up, and they ran. Left behind almost everything. Sold the jewelry for plane tickets, and Natasha became just a name Mami whispered sometimes while shaking her head. Pues, she always said it with the same sadness. The irony is wild when you think on it honestly: Natasha was her true North, but Mami only immigrated North when her own personal North was nowhere to be found.

I’ve always wondered what happened to Natasha, even before I knew who she was. Mami only has one picture of them together, from when they were kids. They’re wearing simple church dresses and standing beside Abuela and her sister. Only Mami is smiling in the picture. Sometimes, Mami just stares at the photo and cries—and Mami doesn’t cry easy at all. Natasha’s image in the photo is so faded it’s like she’s barely there.

I started my documentary as a summer project so I could finally get to the truth about Natasha. Maybe if I could find out what actually happened, no matter what it is, Mami could be at peace. Besides, I needed something to do now that Celeste wasn’t around.

The morning my whole life changed, I hopped out of the shower and rubbed some coconut oil into my hair—like I did any other day. I threw on my light purple track jacket, a comfy Bulls shirt that Lorena stole off one of her boyfriends that I then stole off her (she wasn’t going to wear it anyway), an old pair of jeans, and my worn pair of Adidas Boosts. I like shooting in them because the arch support is fire and they’re this super fly shade of purple, like the sky right before the sun clocks out. Purp, just like my nickname was supposed to be. And then my phone buzzed, but not with the special three quick pops I have reserved for Celeste.

Turned out it was Lorena hitting up the family group chat, which is really just me and her and Mami, because Abuela doesn’t rock with technology like that.

Oye, hermanita, are you still doing your little movie?? Lorena texted.

A frown slashed across my face immediately. This was a big part of why me and Lorena aren’t that close anymore. She never took my work seriously, but I had to take everything she does seriously porque she’s a nerd and goes to U Chicago—like how is that fair? Fun goes there to die. Hard pass!

Yeah. I’m finna ride my bike to the library to see if that book I requested came in so I can do some research, I replied.

Mami started to type a message on the screen: three dots flickering in and out of sight. Her replies take longer when she’s feeling the overtime. Since Papi died, our only income comes from Mami’s job as a shift manager at the restaurant and whatever Lorena kicks back from her campus job. Lately, Mami’s been working later and later, and today she’s typing extra slow, no doubt having to fix spelling errors in her second language, starting and stopping like Lake Shore Drive traffic.

YAY!! I was hoping you’d say that! CANCEL ALL YOUR PLANS!! Lorena texted.

Mami’s text indicator dropped cold and didn’t pick up again.

Y would I do that? I texted back.

Because I got you something even better! Hay un professor who came into the dining hall today, Lorena said.

Typical Lorena. I love her, but the minute she accomplishes something, the whole world just gotta stop and recognize? Give me a break.

Lorena continued to type. And we got to talking and he’s a Doctor of Caribbean Studies who, wait for it …

A GIF of a bunny doing a drumroll appeared. I rolled my eyes so hard I nearly dislocated an iris.

… studies all the disappearances during the Trujillato!!

Oh.

Isn’t this exciting?! I got his office number and everything and he wants to meet with you!! Es perfecto!!

I wrote back: Word, mil gracias. I’ll be over in a bit.

I didn’t want Lorena to know how well she’d done, but she really had knocked it out of the park this time, farther than she had on that old factory roof back in the day. If this was true, then it was the biggest break for the documentary since Mami finally agreed to go on camera and give more than one-word answers.

I grabbed my video camera and placed it delicately in my backpack, cushioning it with old sweaters (also stolen from Lorena), and swung the raggedy black straps over my shoulders. I hustled down the stairs and rushed past the kitchen, almost too fast to catch the mixed scents of purple Fabuloso and arroz con pollo on the stove. My hand whipped for the door. I was the wind, I was the light, I was a waiting arrow of truth!

“Pilar Violeta Ramirez!! ¡¿A dónde vas?!”

I was … a twelve-year-old with a curfew and mad chores.

“Pero, Mamiiiiiii…”

“¡Ven aqui!”

When I entered the kitchen, the Fabuloso smell took a back seat to the sharp butter-and-adobo scent of the arroz. Something about the way Mami cooks makes me feel like there should be music accompanying it. She turns rapidly between dishes, una media vuelta that never betrays how heavy and swollen her feet are after a shift. She was grace personified, and if I were lighting the scene, I’d use only the softest pinks. For the score, I’d choose some bachata with a lot of guitar, an overly sweet love song like the kind you can only find on Mami’s old CDs.

“¿Pilar, a dónde vas?” she asked without looking up, as if she could smell that I hadn’t done any chores and I wouldn’t be back for a long while.

“Did you see Lorena’s text? I’m going to meet with her professor.”

“¿Sobre qué?”

“For the documentary. The one on—”

“Ay, Negrita, por favor, why can’t you just accept that some things are what they are? Some things, they just—can’t be changed. A veces people are just—” By accident she dropped her stirring spoon, sending a few undercooked grains into the sticky kitchen air before the utensil clattered to the floor like a clave. Even when she dropped things there was music.

“Pero, Mami,” I said, reaching for the spoon. “I just need to learn a few more things and shoot some B-roll. And then we’ll be in postproduction.”

Mami sighed while she picked up the spoon, then cupped my face with a sadness in her eyes, which are the color of old brick.

“I’m just saying, mijita, you have been out of the house a lot when I need you here. This neighborhood”—the room was quiet except for the soft bubbling of the pot—“it’s changing. I–You can’t just come and go anymore. You’re changing, too, entiendes? Things are different now.”

“I understand, Mami, pero…” While trying to come up with the best response, I cast my eyes around the kitchen. Finally I tossed down Lorena’s signature get-out-of-jail-free card: “Just think of the opportunity, Mami. A professor wants to meet with me! Maybe I could go to college where Lorena goes. Wouldn’t you like that?”

I hoped lying wouldn’t give me cavities, even though technically what I’d said wasn’t a lie. I do want to go to college, but film school, not Lorena’s Nerdtopia.

Something softened in Mami’s round brown face and she pushed both hands over her thick graying curls. Mami’s hands are always like birds, jittery and soft and fast. They skimmed over her hair like gulls flying across Lake Michigan when the streetlights are about to cut on.

“You be home before dark. Or else El Cuco will get you.” She grinned sadly, like she could still see the little girl I used to be, the one who was afraid of El Cuco, the Dominican Boogeyman.

It wasn’t a question, but I nodded anyway. She waved her hand toward the door like she was too weary for more words. Maybe she didn’t approve, or maybe we were both learning that soon I would be too fast and she would be too exhausted to stop me. Either way, I was already out the door and unlocking my bike from the gate. I rode hard and fast toward the Blue Line and out of my neighborhood where everything was changing—and right into the day that would change me forever.

Copyright © 2022 by Julian Randall