introduction

by Mary Robinette Kowal

I met John Scalzi at a writers’ conference when he was already well known for his blog, Whatever, but before he had won the Astounding Award for Best New Writer. He was nominated for it, but I’d never heard of him or anything he’d written. So this is an “I knew him when” story.

What struck me was that he was clever and funny, but that he also used that humor to make points about real things that were important. I honestly don’t remember what we talked about, because we talked for hours over a huge range of subjects. What I do remember was thinking, “I need to read one of his books.”

Followed by fear.

There’s a thing that happens when all of your friends are writers. You want to read their work and you are also terrified to read it, because what if it sucks? The novel that everyone was talking about was Old Man’s War, which is not this book. Redshirts is way in the future of this story. I was hesitant, because it was military SF, which is not usually my jam.

He had me crying within the first ten pages. Damn him. And also thank God the man can write.

So now he exists in two forms in my head. John, my friend, and Scalzi, the writer. I’m a fan of both. I have read everything he’s written at this point and while I love a lot of my other author friends, he’s one of the few whose books I leap on the moment they come out. Who am I kidding? I pester him for the manuscript as soon as he turns things in.

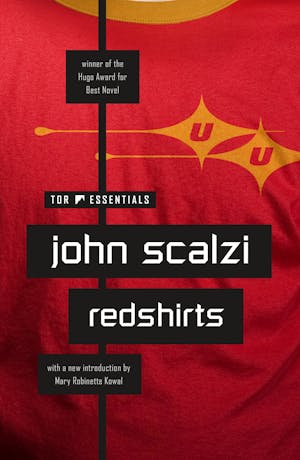

Which brings us to Redshirts.

This is a very different book from the one I fell in love with and yet true to all of Scalzi’s strengths. It’s a comedy that plays with the tropes of science fiction while also strictly adhering to them. Scalzi has a saying about people trying to be funny on the internet. “The failure mode of clever is ‘asshole.’” This book is clever.

One of the traits that I love about his writing is that it is often secretly subversive. In this case, he begins the book as something that feels like a parody of Star Trek. And it is. But as you go deeper into the novel, he retains the bite from the parody and slowly transforms it into an entirely different kind of book. In another author’s hands, this would be a bait and switch.

But this book is clever and not an asshole. Scalzi promises you a fun ride and he delivers that. He just doesn’t stop there.

Now, having said that, I want to also say that the fact that this is a comedy is important. When we laugh, we become a tiny bit vulnerable and that allows an adept author to sneak truths in. If someone wants to write a book about the meaning of life and questions of predestination, they could do it in a weighty tome. Readers can sometimes brace against that and rail against message fiction. But comedy like Redshirts stages a sneak attack and makes you laugh. While you’re chuckling, it sinks in the hooks of the questions that linger long after the book is finished.

Comedy is also harder than tragedy. Let me be really clear about this. Comedy. Is. Hard. With tragedy, you just have to keep making things worse and you don’t really have to worry about solving whatever terrible bind you’ve put your characters in. To be funny relies on having a shared context and expectations that you then break. Breaking those expectations requires originality, because the laugh often comes from a surprising juxtaposition. I mean, don’t get me wrong, poop jokes will always be funny because most of us are still five years old inside, but even that comes from a break of societal expectations.

Linguist Tom Veatch proposed a theory called “benign violation,” which posits that humor occurs when three conditions are satisfied: (1) a situation is a violation, (2) the situation is benign, and (3) both perceptions occur simultaneously.

For instance, did you know that the Apollo missions left nearly one hundred bags of fecal matter on the moon? That’s science and benign. Not funny. Well, not very funny. Earworms are a violation. Therefore, I present to you … “Ninety-nine bags of poop on the moon, ninety-nine bags of pooooop.”

Is that high comedy? No, it is not. But it demonstrates how hard comedy is. The benign violation theory also explains why the failure mode of clever is “asshole.” Just because a violation is benign to you, doesn’t mean that it’s benign to someone the joke is about. By taking Star Trek and starting with a parody of it, Scalzi can immediately dive into benign violation of all of your expectations.

Also, I am not sorry about the benign violation of that earworm. “Take one down, pass it around, ninety-eight bags of…”

My point is that in making Redshirts a comedy, Scalzi is doing something hard and making it look effortless. Telling a joke in person is tricky, but you can judge your audience’s reaction and adjust timing accordingly. A novel is an asynchronous experience that is sometimes written years before the audience sits down to read it. I mean, Jane Austen is hilarious but a lot of the jokes have vanished with their context.

Which is why the fact that Redshirts is more than just funny is important. Scalzi uses that humor to pry apart our expectations and understanding and he’ll make you cry by the end. Damn it. The man can write.

prologue

From the top of the large boulder he sat on, Ensign Tom Davis looked across the expanse of the cave toward Captain Lucius Abernathy, Science Officer Q’eeng and Chief Engineer Paul West perched on a second, larger boulder, and thought, Well, this sucks.

“Borgovian Land Worms!” Captain Abernathy said, and smacked his boulder with an open palm. “I should have known.”

You should have known? How the hell could you not have known? thought Ensign Davis, and looked at the vast dirt floor of the cave, its powdery surface moving here and there with the shadowy humps that marked the movement of the massive, carnivorous worms.

“I don’t think we should just be waltzing in there,” Davis had said to Chen, the other crew member on the away team, upon encountering the cave. Abernathy, Q’eeng and West had already entered, despite the fact that Davis and Chen were technically their security detail.

Chen, who was new, snorted. “Oh, come on,” he said. “It’s just a cave. What could possibly be in there?”

“Bears?” Davis had suggested. “Wolves? Any number of large predators who see a cave as shelter from the elements? Have you never been camping?”

“There are no bears on this planet,” Chen had said, willfully missing Davis’ point. “And anyway we have pulse guns. Now come on. This is my first away mission. I don’t want the captain wondering where I am.” He ran in after the officers.

From his boulder, Davis looked down at the dusty smear on the cave floor that was all that remained of Chen. The land worms, called by the sound of the humans walking in the cave, had tunneled up under him and dragged him down, leaving nothing but echoing screams and the smear.

Well, that’s not quite true, Davis thought, peering farther into the cave and seeing the hand that lay there, still clutching the pulse gun Chen had carried, and which as it turned out had done him absolutely no good whatsoever.

The ground stirred and the hand suddenly disappeared.

Okay, now it’s true, Davis thought.

“Davis!” Captain Abernathy called. “Stay where you are! Any movement across that ground will call to the worms! You’ll be eaten instantly!”

Thanks for the useless and obvious update, you jackass, Davis thought, but did not say, because he was an ensign, and Abernathy was the captain. Instead, what he said was, “Aye, Captain.”

“Good,” Abernathy said. “I don’t want you trying to make a break for it and getting caught by those worms. Your father would never forgive me.”

What? Davis thought, and suddenly he remembered that Captain Abernathy had served under his father on the Benjamin Franklin. The ill-fated Benjamin Franklin. And in fact, Davis’ father had saved the then-Ensign Abernathy by tossing his unconscious body into the escape pod before diving in himself and launching the pod just as the Franklin blew up spectacularly around them. They had drifted in space for three days and had almost run out of breathable air in that pod before they were rescued.

Davis shook his head. It was very odd that all that detail about Abernathy popped into his head, especially considering the circumstances.

As if on cue, Abernathy said, “Your father once saved my life, you know.”

“I know—” Davis began, and then nearly toppled off the top of his boulder as the land worms suddenly launched themselves into it, making it wobble.

“Davis!” Abernathy said.

Davis hunched down, flattening himself toward the boulder to keep his center of gravity low. He glanced over to Abernathy, who was now conferring with Q’eeng and West. Without being able to hear them, Davis knew that they were reviewing what they knew about Borgovian Land Worms and trying to devise a plan to neutralize the creatures, so they could cross the cave in safety and reach the chamber that housed the ancient Central Computer of the Borgovians, which could give them a clue about the disappearance of that wise and mysterious race.

You really need to start focusing on your current situation, some part of Davis’ brain said to him, and he shook his head again. Davis couldn’t disagree with this assessment; his brain had picked a funny time to start spouting a whole bunch of extraneous information that served him no purpose at this time.

The worms rocked his boulder again. Davis gripped it as hard as he could and saw Abernathy, Q’eeng and West become more animated in their attempted problem-solving.

A thought suddenly came to Davis. You’re part of the security detail, it said. You have a pulse gun. You could just vaporize these things.

Davis would have smacked his head if the worms weren’t already doing that by driving it into the boulder. Of course! The pulse gun! He reached down to his belt to unclasp the gun from its holster. As he did so another part of his brain wondered why, if in fact the solution was as simple as just vaporizing the worms, Captain Abernathy or one of the other officers hadn’t just ordered him to do it already.

I seem to have a lot of voices in my brain today, said a third part of Davis’ brain. He ignored that particular voice in his brain and aimed at a moving hump of dirt coming toward his boulder.

Abernathy’s cry of “Davis! No!” arrived at the exact instant Davis fired, sending a pulsed beam of coherent, disruptive particles into the dirt mound. A screech emanated from the mound, followed by violent thrashing, followed by a sinister rumbling, followed by the ground of the cave erupting as dozens of worms suddenly burst from the dirt.

“The pulse gun is ineffective against Borgovian Land Worms!” Davis heard Science Officer Q’eeng say over the unspeakable noise of the thrashing worms. “The frequency of the pulse sends them into a frenzy. Ensign Davis has just called every worm in the area!”

You couldn’t have told me this before I fired? Davis wanted to scream. You couldn’t have said, Oh, by the way, don’t fire a pulse gun at a Borgovian Land Worm at our mission briefing? On the ship? At which we discussed landing on Borgovia? Which has fucking land worms?

Davis didn’t scream this at Q’eeng because he knew there was no way Q’eeng would hear him, and besides it was already too late. He’d fired. The worms were in a frenzy. Somebody now was likely to die.

It was likely to be Ensign Davis.

Through the rumble and dust, Davis looked over at Abernathy, who was gazing back at him, concern furrowed into his brow. And then Davis was wondering when, if ever, Abernathy had ever spoken to him before this mission.

Oh, Abernathy must have—he and Davis’ father had been tight ever since the destruction of the Franklin. They were friends. Good friends. It was even likely that Abernathy had known Davis himself as a boy, and may have even pulled a few strings to get his friend’s son a choice berth on the Intrepid, the flagship of the Universal Union. The captain wouldn’t have been able to spend any real time with Davis—it wouldn’t have done for the captain to show favoritism in the ranks—but surely they would have spoken. A few words here and there. Abernathy asking after Davis’ father, perhaps. Or on other away missions.

Davis was coming up with a blank.

Suddenly, the rumbling stopped. The worms, as quickly as they had gone into a frenzy, appeared to sidle back under the dirt. The dust settled.

“They’re gone!” Davis heard himself say.

“No,” Abernathy said. “They’re smarter than that.”

“I can make it to the mouth of the cave!” Davis heard himself say.

“Stay where you are, Ensign!” Abernathy said. “That’s an order!”

But Davis was already off his boulder and running toward the mouth of the cave. Some part of Davis’ brain howled at the irrationality of the action, but the rest of Davis didn’t care. He knew he had to move. It was almost a compulsion. As if he had no choice.

Abernathy screamed “No!” very nearly in slow motion, and Davis covered half of the distance he needed to go. Then the ground erupted as land worms, arrayed in a semicircle, launched themselves up and toward Davis.

And it was then, as he skidded backward, and while his face showed surprise, in fact, that Ensign Davis had an epiphany.

This was the defining moment of his life. The reason he existed. Everything he’d ever done before, everything he’d ever been, said or wanted, had led him to this exact moment, to be skidding backward while Borgovian Land Worms bored through dirt and air to get him. This was his fate. His destiny.

In a flash, and as he gazed upon the needle-sharp teeth spasming in the rather evolutionarily suspect rotating jaw of the land worm, Ensign Tom Davis saw the future. None of this was really about the mysterious disappearance of the Borgovians. After this moment, no one would ever speak of the Borgovians again.

It was about him—or rather, what his impending death would do to his father, now an admiral. Or even more to the point, what his death would do to the relationship between Admiral Davis and Captain Abernathy. Davis saw the scene in which Abernathy told Admiral Davis of his son’s death. Saw the shock turn to anger, saw the friendship between the two men dissolve. He saw the scene where the Universal Union MPs placed the captain under arrest for trumped-up charges of murder by negligence, planted by the admiral.

He saw the court-martial and Science Officer Q’eeng, acting as Abernathy’s counsel, dramatically breaking down the admiral on the witness stand, getting him to admit this was all about him losing his son. Davis saw his father dramatically reach out and ask forgiveness from the man he had falsely accused and had arrested, and saw Captain Abernathy give it in a heartrending reconciliation right there in the courtroom.

It was a great story. It was great drama.

And it all rested upon him. And this moment. And this fate. This destiny of Ensign Davis.

Ensign Davis thought, Screw this, I want to live, and swerved to avoid the land worms.

But then he tripped and one of the land worms ate his face and he died anyway.

From his vantage point next to Q’eeng and West, Captain Lucius Abernathy watched helplessly as Tom Davis fell prey to the land worms. He felt a hand on his shoulder. It was Chief Engineer West.

“I’m sorry, Lucius,” he said. “I know he was a friend of yours.”

“More than a friend,” Abernathy said, choking back grief. “The son of a friend as well. I saw him grow up, Paul. Pulled strings to get him on the Intrepid. I promised his father that I would look after him. And I did. Checked in on him from time to time. Never showed favoritism, of course. But kept an eye out.”

“The admiral will be heartbroken,” Science Officer Q’eeng said. “Ensign Davis was the only child of the admiral and his late wife.”

“Yes,” Abernathy said. “It will be hard.”

“It’s not your fault, Lucius,” West said. “You didn’t tell him to fire his pulse gun. You didn’t tell him to run.”

“Not my fault,” Abernathy agreed. “But my responsibility.” He moved to the most distant point on the boulder to be alone.

“Jesus Christ,” West muttered to Q’eeng, after the captain had removed himself and they were alone and finally free to speak. “What sort of moron shoots a pulse gun into a cave floor crawling with land worms? And then tries to run across it? He may have been an admiral’s son, but he wasn’t very smart.”

“It’s unfortunate indeed,” Q’eeng said. “The dangers of the Borgovian Land Worms are well-known. Chen and Davis both should have known better.”

“Standards are slipping,” West said.

“That may be,” Q’eeng said. “Be that as it may, this and other recent missions have seen a sad and remarkable loss of life. Whether they are up to our standards or not, the fact remains: We need more crew.”

Copyright © 2012 by John Scalzi

Copyright © 2021 by Mary Robinette Kowal