Before his flight to Earth, they had warned Jonathan about the “gangs.” Even at the Stamford Station where his shuttle had docked, even on the bullet train that spirited him north past brick apartment buildings and houses with gables and turrets, manicured lawns, circular drives, bay windows, even past the shorefront homes of South Norwalk with sailboats parked on the sand or tethered to metal docks fashioned to look as though they were made out of peeling wood, made to look as though they had been there forever, past the kayaks and the fountains and the parks populated by poplars and willow trees, they warned him about the gangs. The admonitions were grave and ominous every time they issued from someone’s mouth, but the closer he came to the frontier, the grimmer the admonition. Their crimes, their violence, their predilections grew more and more specific, the anecdotes spawning increasingly specific limbs until Jonathan was made to believe that he could discern the very contours of the lusus naturae waiting for him in New Haven. People who knew people he knew offered their numbers and their contacts, so that once Jonathan arrived, he could pass word of his safe landing. The land was red and burning where he was headed, and if he were not careful, he’d burn too.

He had thanked each and every Cassandra, noted that he would heed their advice, but inwardly, he was grinning. He was shaking his head and grinning. Among the things they didn’t know was the sheer strength of Jonathan’s thirst for shadow country, the fact that he had wanted to build something ever since the first dreams of returning to Earth had entered his head, that he had spent nearly every waking moment dissecting his plan, putting it back together, testing the foundation and the buttresses and the supports, making sure the electricity worked and that the plumbing was done with a strong enough piping. And gangs. The invariably white folk who cautioned Jonathan against youthful bravado, against infantile nonchalance, knew that gangs existed, which is to say they knew as much as anybody did about gangs, which is to say they knew nothing.

They said gang, and he knew they meant Black. They said thugs, and he knew they meant the n-word.

There were a lot of empty factories in New Haven, which is saying nothing, as Jonathan knew there were a lot of empty factories everywhere in America. When he was a child, those relatives still on Earth, old enough to be dug in at the roots and either too infirm or too set in their ways to make the pilgrimage to the Colonies, would send transmission after transmission to regale their grandson, grandnephew, old friend’s child, of places like the Rust Belt. It sounded to Jonathan like a stylish thing wrapped around the waist of a skinny guy with dark and mysterious inclinations, an aura of enticing hurt, the kind of guy Jonathan would want to fix by fucking.

Jonathan’s bees sprouted from his hair, buzzed around his head recording the landscape’s deterioration. The images beamed, as soon as they were taken, to David’s Cloud back on the Colony, a little delayed due to spotty connection.

Stories of the radiation had made their way to the Colonies and even still with the documentation, with the filtered photos on everyone’s ’grams and with the news updates and with the video taken by people on their way out, the whole thing had acquired an air of myth. It had always been something that had happened to someone else. The truth was that Jonathan knew no one still on Earth, knew no one who had stayed or had been forced to stay, and he saw it as a deficiency. Life was truly lived here, where it was at stake. The forests were bright green and, as he approached the terminus of the train line, bright red, a vibrancy nowhere to be found in space, where everything was a different shade of gray, where every panel and every pathway was drained of color and only the bricks that came imported from Earth seemed to bear any trace of having had a full and exacting life.

Jonathan collected his bags from the train’s undercarriage, then hailed a small personal transport, room for one, that took him past the Protected Zone and into some of the forest outside of Fairfield County. Prior to his departure, they’d made him print out all of his documents and when, now, his comms fritzed with static and his ’gram shots took longer than usual to make their way online, he saw why. The Soviet insistence on printing everything in quintuplet, and the months and months of phone calls and emails prior, had been meant to reassure the authorities on the Colonies that he was no longer their ward. The umbilical cords linking Earth and the Colonies had been snapped. You came here wanting to be forgotten, wearing the odor of an outlaw. The mindset up in the stars was that anyone returning, unless they were seeking to gather family, had nothing left on the Colonies, no reason to enjoy the banal comforts and the safety of the Space Station. If you were leaving, it was because you had been defeated.

There were no more pioneers left in space.

Bridgeport Harbor was now in their rearview. The bees buzzing around Jonathan’s hair beamed into his braincase information about the industrial husks that floated by: St. Vincent’s Medical Center, which, once upon a time, had been the city’s biggest employer; People’s United Bank; University of Bridgeport; Housatonic Community College; the Derecktor Shipyards. Wikis on each of the landmarks bookmarked themselves in Jonathan’s braincase, and as soon as he scanned them, they vanished into a folder waiting to be trashed. He chuckled and, under a ’gram he snapped of a row of two-story project housing, he murmured a caption in a newscaster’s voice: “And here we have Bridgeport, Connecticut, world leader in abandoned buildings, shattered glass, and gas stations without pumps. Come here to see boarded-up windows and wild dogs like no other.” Except the dogs here were larger than they were supposed to be and mixed in with all of the industrial decay was a wrongly colored forest, retaking control of the city.

They passed the Ballpark at Harbor Yard where the Bridgeport Bluefish used to play and, before long, they took the off-ramp that put them on Whitney Avenue in New Haven.

Jonathan put his palm to the cabbie’s scanner, then pulled it away, frowning, when he saw how much he’d been charged. But before he could complain, the maglev transport was stopped and his luggage was out on the street corner and he’d fumbled for his air mask, barely getting it on before the cab whirled around and sped down a side street, winding its way back onto the Interstate.

Across the street from Jonathan, on a sidewalk torn to pieces by weeds and renegade tree roots, stood what might have once been called a wild boar. This one, however, more resembled a demigod. On four legs, it rose as high as Jonathan’s chest, poked at the air before it with a snout longer than it was supposed to be. The spiny bristles ran along its back like hypodermic needles, and its pointed ears wagged to full mast then back down. The sun washed it in shades of ochre and gray. It stared at Jonathan with wild-eyed wonder. It was only after the thing had wandered away, on spindly, overlong legs, that Jonathan realized his own strangeness, the air mask affixed to his face still a foreign object and he very much a stranger in a strange land.

* * *

“NAME something that follows the word ‘pork.’” Michael sounded like he was pushing the demo-truck rather than driving it.

“Loin,” Linc said.

The truck groaned. The neighborhood was quiet, exactly how it’d sound if there were no neighbors in it. “Gimme another one.”

“Chop.”

“Brother, you hungry or something?”

“Belly. Pork belly.”

“Okay, after this house we’ll hit the bodega.” Silence. “You got another one for me?”

Linc thought. “Cupine.”

Quietus. “What?”

“Tell me that ain’t an answer,” Linc shot back.

Michael chuckling. “Pork. Cupine.” His seat began to shake. “Cu…” The rest was choked in a fit of laughter. “Cupine.” Convulsions rocked the cab of the truck. “HWHAT?” Thunderclaps of laughter. “HHWHATT? Is CUPINE?” The truck swerved, Michael laughed so hard.

“Damn, nigga.”

“I’m sorry. I’m sorry.” He was probably wiping tears from his eyes right now. Sniffing away excess mirth. “But that’s the greatest answer I’ve ever heard.”

“It’s the right answer.”

“I feel you, brother. I feel you.”

“On my mama.”

“Pow, brother.” Another crippling fit of laughter. “Damn, brother, I wish I were recording this. I tell you what, you ask anyone else. Anyone else, they tell you the same. That you the only person who said ‘cupine.’ I bet you every dollar I got.”

The truck straightened its course, resumed its lumbering deliberateness, Michael muttering the “cupine” beneath his breath and trying not to let his howling kill them both.

The sky bled across the clapboard houses that lined the road. Wood domiciles and brick edifices. Single-family homes made after a war that happened before Linc’s father’s father had been a man. The twelve-wheeled demolition truck hovered over the ground, the maglev strips under the concrete still in working order. Kind of. But the truck rumbled nonetheless. The noise the engine made had the truck huffing like a fat man rounding a corner. The heat and the humidity conspired to stain Michael’s third shirt of the day a new color. Linc had stripped down to a tank top and jeans. Even the truck’s brow beaded with sweat.

Linc sat in the space between the truck’s cab and its bed, that shifting connector where overhead hung the lip of the trashbed. Shade was shade.

He heard the neighbors before he saw them; female voices, generations of motherhood, streamed out of their houses to gripe. Mothers taking care of their mothers, other women taking care of their grandkids, bouncing them on their hips, managing, just by touch, to cool those poor kids down so that they didn’t look like black porcelain dolls in the light. They came out one by one, then began to line the streets like trees, following the truck’s course.

“When them dead trees coming down?” came a voice from behind the trashbed. They asked like Linc had any say in the matter, like they could even see him and his hammer at all. “When you gonna stop them kids from pushing that dope two houses down from here? I’m pickin’ up goddamn needles every goddamn morning!” Someone caught sight of Linc. “You got a job for my son? He’s lookin’ and he’s able to work. Healthy as whatever, no lung rot or nothin’.” Another: “My nephew! You can git him some work, he’s willin’ to do it.” Another: “Hell, I can lift just as good as any of ’em. Them checks from Fairfield ain’t enough to feed a dog kennel, let alone this family I got here.” They announced how well they could tap a water vein and run a hose, how easily they could heft a shovel, how the dying of the earth hadn’t yet crushed them, but when Michael’s truck stopped, they didn’t crowd. This had all happened before.

Linc shifted, ready to hop out from his space. The women started pointing to the abandoned houses on the street. One of them, in a purple blouse, a baby in one arm, the other hand dabbing her forehead with a kerchief, stepped forward. “You finally gonna tear this one down? I been callin’ the city for months now. Months!” Another woman beside her stepped up, left behind a little girl who fidgeted with her sundress. “How ’bout that one?” She pointed to another duplex three houses down with a massive tree trunk bursting through to the second floor, branches sprouting out the windows.

Michael leaned out the driver’s side window, squinted beneath the brim of his insignia’ed ball cap. “I’m only here for that house over there.” He nodded toward a spot two houses in from the corner. A two-bedroom with a gable roof, one half of its second-floor façade charred. The porch was missing its bricks. Some of them saw Linc descend and their target reticles zeroed in on him.

“You tellin’ me you’re here for just one house? One house?” This one wearing an orange blouse and holding close to her face a tiny solar-powered water-fan. She swept her arms to indicate the row of houses across the street from the one targeted for demolition. “Those are all drug houses. Someone got raped in that one on the corner. I called about that one! I been calling all week. I called and called.”

Linc’s shirt caught on the edge of a groove and the sun lit the puckered course of a scar that ran along the skin just above his hip. An almost-healed souvenir from a house he had cleared a few weeks back. He pulled his shirt down, dragged his hammer off his seat, and hefted it over his shoulder.

“I’m just a wrecker,” Michael pleaded. “The mayor don’t forward no calls my way.” He spoke with a bit of a Puerto Rican lilt; certain vowels and consonants would rise like he was inviting himself over for dinner. The city sent Michael to this part of town pretty often. Linc didn’t know how Michael was gonna break it to those ladies that he did have other houses to demolish today but that the rest of those twenty houses stood on the other side of the city.

Linc shuffled toward the house that must have preceded the urban renewal projects that swept through the city during the beginning of the millennium. The houses like these, they were like the Pyramids in Egypt. It made sense that humans had built them, but without the stuff that they had now, such things seemed an impossibility. Digging the hole and filling it with foundation. The ceiling joists and the floor bridging. They probably laid the shingles that had once upon a time been there one by one. Pulleys and men with tool belts. Wood siding put in manually, mortar spread, bricks stacked. Maybe the house had once upon a time been beautiful. The fulfillment of a promise. You work hard, you strive, you take out a loan, and you move along with the business of starting a family. Now, the thing’s roof had caved in, trees grew throughout it, and summer heat had made the bulging walls crisp. The women had complained about drug dealers and rapes; some of these places had probably hosted more than a few murders.

The counsel Michael held with the ladies turned to a muffle. Linc entered and could see that the scavengers had been recent here. The floor was soft with mold, shifted beneath his footfalls. Out back, there had probably been a rusted van, maybe without doors, to make it easier for the vultures to load the furnace and the stove, the piping that they had picked out from behind the walls. Maybe they were at this very moment getting paid for their scrap metal. It all probably happened in the time between when the dangerous-buildings inspector had phoned Michael and when Michael had picked Linc up from his apartment. A large, person-shaped lump stopped Linc’s boot and he kicked the thing over to find the remains of a face staring up at him. Parts of the body had been gnawed away, some of the fingers down to the bone, the eyes still there, but the cheek jowls torn and hanging. Traces of quicklime lined the corpse. He’d been told to report corpses, maybe they would help out with open investigations. Linc stepped over the thing.

In another room, on top of a molding, rust-pitted mattress slept a wraith. Next to that wraith’s head, just underneath its opened hand, was a Tec-9. Red-tops and yellow-tops, wrapped in small plastic bags, peeked out from inside a crinkled paper sack. Linc stooped, gingerly pulled the Tec out from beneath the emaciated hand, doubted the person could have lifted it anyway, pulled out the clip and stuffed it into his pants’ pocket. He ejected the bullet in the chamber and tossed the thing into a pile of empty burger wrappers. His hand tightened on the neck of his hammer. The junkie was dissolving into the ruins, turning into the house ready for demolition, and its head would’ve been easy enough to crash in. The junkie was done living anyway, but Linc moved on.

Descending into the basement, he noted the water damage, but it was far enough along to show that the water had been turned off some time ago. Nothing had lived in there for a long time now. He stayed on the concrete steps for a while, frozen, reminded of the time he’d come down into a similar basement to find a little boy cuffed to a radiator after having passed a man ambling out the back door and buttoning up his pants. He blinked away the vision. Nothing stirred. And if, like the junkie, anything were still breathing, it wouldn’t get anything approaching a proper burial. The local cemeteries had long since burst through their capacity.

He came back up for air. The board-up crew had already sealed off most of the space. A roving band of custom-cut sheets of plywood and screw guns. They moved like whirling dervishes, and sometimes their haste left shoddy work in their wake, like bodies that they hadn’t accounted for, the ignored junkie or rape victim or dead body or eco-freak trying to make art out of ruin porn.

Coming out of the house felt like emerging from hell. The light blinded. The air, poisoned as it was, cleansed the lungs. The mind-fog and the shell shock dissipated, and all of a sudden, there were new parking lots or bits of road or signage that he hadn’t noticed before. Everything seemed draped in clarity. In focus.

Linc gave Michael the thumbs-up. House cleared. His hammerhead dragged behind him.

Michael nodded, then opened his dashboard and out came a small console with a touchboard protruding from its bottom. Empty stimhalers tinked against each other as he stretched and geomapped the house’s location, input the coordinates, and armed the drone that would arrive in just under five minutes. There was shade at the bunker, and a radio where he could tune in to the ball game or put on a playlist, and he could operate the drone from there. The console was bigger there, had more equipment and became much more of an immersive experience. Plus, the operating room was air-conditioned. But he had grown to hate it. He needed to be around the people.

On the console would be a high-definition moving image, turning the northwest of New Haven, a span of about a dozen or so blocks, into a midsummer palette of copper and brown and gray, punctuated by occasional, invasive green. The houses, in rows, would be easy enough to pick out, but it was always when he switched to infrared, waiting for heat signals, that the cracks would run through his heart. The ghostly white always stood out against the irradiated landscape, and there was always movement, sometimes the smallest of gestures, until there wasn’t. He would linger over well-populated neighborhoods to remind himself that people still lived here, but when he’d have to head over to his target, the blotches would drop off until there was only a blood-red sea below, all twenty-three homes on a once-busy block empty. Sometimes, a single white snowflake would move among the red, an amoeba lumbering among the charred husks of thirty-five neighboring vacancies.

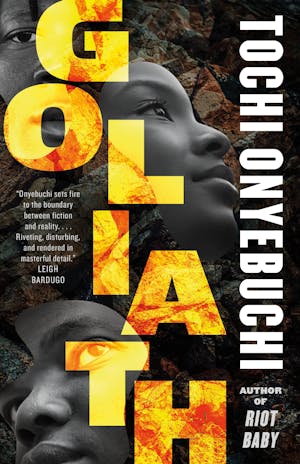

Copyright © 2021 by Tochi Onyebuchi