KENTUCKY, 1929

I.

The passenger train heaved to a stop at Hazard station. Coal smoke from its stacks silted the muggy air. Leslie Bruin took his cap from his knee and his travel bag from beneath his seat, tucking the former over a crop of wavy hair and the latter over a ride-sore shoulder. The train car, sleepy throughout the trek from Louisville, now bustled: girls laughing, bags thumping floorboards, the cigarette man calling out to disembarking passengers. Leslie traded a quarter for two packs as he stepped onto the platform. The end-of-summer heat hadn’t cracked in the eastern counties, and a small crowd loitered in the station house shade eyeing the new arrivals. Porters offloading luggage hollered directions down-platform. With a sigh, Leslie turned toward the clamor to rescue his saddlebags.

“Miss Bruin,” called a tall, sun-worn gentleman across the way.

Miss was far from his preferred form of address, but Leslie pasted on a smile regardless, as he recognized the speaker. “Good to meet you again, Mister Hansall.”

“Jackson is fine, ma’am,” he said, convivial grin creasing his face. “There’s a car ready to drop us at the travel post. You need any refreshment before we hit the road?”

“I could use a sip of water, once I’ve collected the bags. Shall we?” Leslie gestured to the porters.

“Don’t worry yourself, I’ll carry those,” Hansall said.

The nurses of the Frontier Service had no trouble lugging around their supplies, or else how would the work get done, but rather than kicking up a fuss Leslie smiled and nodded—amiable, businesslike. Hansall returned the sentiment with a tap to the brim of his hat and set off to make himself useful.

A squat, glittering geode propped open the station house door; the stenciled glass announced “Whites Only.” South of the Ohio River those signs fruited like fungus on rotten wood. At least a quarter of the ladies whose drinks he’d stood while traipsing across Chicago on leave would be banned from stepping over the threshold—but in need of a piss and a cold drink, he crossed unimpeded. A ceiling fan stirred stale air. The solitary girl at the counter squinted at his trousers and cotton shirt then said, “Good afternoon, Nurse.”

“Am I so obvious?” Leslie asked.

She rolled her eyes. “Would any other woman wear pants and boots in this weather?”

“Then I’m caught out,” he said. “A soda, please?”

“Comin’ right up.”

As she bent to open the refrigerator the loose collar of her dress flashed silk brassiere and cleavage. Leslie stuffed his hands in his pockets, wrenching his gaze away. The clerk sat a perspiring bottle of Coca-Cola on the countertop. He swigged a mouthful of syrupy fizz and she watched silently with arms crossed under her breasts. In a city whose rules he understood, he might’ve chatted to her, but out here the risks outweighed the rewards considerably.

When a family came through the door with one caterwauling babe in arms, Leslie set his Coke aside. Given he’d already been read by the clerk he ducked into the ladies’ restroom to do his business, emerging to find Hansall by the station entrance: hip cocked and cap beneath his arm, short sleeves cuffed nigh to the shoulder. His maleness carried such ease.

“Ready whenever,” he said.

A dusty Ford awaited, its driver hanging an arm out the window. Leslie boosted himself into the truck bed beside his saddlebags. It was twenty-five miles of paved road in the Model A, then another fifteen on horseback before reaching Spar Creek—ideally ahead of nightfall. The isolated mountain town was Leslie’s farthest post since rostering on with the FNS in ’25, as well as his first without a partner, but Breckenridge’s orders were clear. With luck Leslie would see babies birthed, children vaccinated, and adults’ ailments resolved in record time; without luck, he’d be wintering in the hills.

Hansall thumped the quarter panel like a mare’s flank and asked, “Mind if I ride in the cab?”

“Suit yourself, I’ll rest back here,” Leslie answered.

“You army girls are too tough for me.” His chuckle was fond and dismissive.

The automobile creaked when Hansall clambered in. Leslie dropped his head against the wooden rail. Sunlight beat down meanly, so he dragged his cap over his face, breathing in the funk. Sweat prickled beneath his armpits and breasts. No worse than silent afternoons spent on the front by the River Marne, rotating rest shifts on the ambulance cot with a fellow nurse, their once-starched uniforms limp with the sweat of terror and exhaustion. Nothing, ever again, could possibly be so bad as the terminal months of ’17 and the gore-fetid soil of Champagne—the brief season of life from which he was sometimes unsure he’d returned. Frontier nursing might not fit his unsettled spirit, but it was the closest he’d found to meaningful labor in his decade stateside. At least delivering infants and stitching up farm accidents provided his trained hands with work while his agile, ugly brain strayed, and strained, and gnawed upon itself.

The Ford rattled out of the gravel lot, breeze nipping through the buttons of his shirt. The ride steadied as they reached the road, and as green foothills rose around them—the spurs of mountains older than time—Hazard fell away from view. Anticipating long hours on horseback, Leslie coasted into the twilight place ahead of sleep: arms crossed loose over his belly, chin drooping, leg notched over his pack. When a letter had summoned him back from leave he’d expected an assignment to the newly christened Hyden Hospital. Instead, the note informed him that the minuscule town of Spar Creek had requested a nurse—with Leslie’s own name already appended by a local, Jackson Hansall, whom he’d met during a previous rotation at the coal mine another town over.

He’d been considering quitting the service to see if this time he could wedge himself into the role expected of him in the city: nightshift at a factory, an apartment safe enough for his girl to bring clients around, and constant vigilance against nosy neighbors ratting them out. He’d almost resolved to turn down the assignment. Then he’d come home from the bars to find another Dear John missive neatly folded on his bedside table, sealed with a mauve lipstick print and telling him what a sweet husband he’d make for some other girl, some other time. The FNS summons that arrived on its heels at least offered the comfort of orders to be followed.

The truck jounced to a halt, rousing Leslie from his stupor. He tucked his cap through his belt and mopped his face dry. A traveler’s stable large enough to house twenty horses awaited them, its barn doors open wide. Manure and hay stink merged with the verdancy of the woods. Hansall rounded the backside of the truck at the same moment Leslie hopped down from the tailgate.

“If there aren’t problems on the trail, we’ve got about five hours’ ride ahead,” he said.

Raspy with road dust, Leslie said, “Then let’s get to it.”

Bidding their driver farewell, supplying two fresh horses, and heading out along the dirt track toward Spar Creek took less time than expected. Old-growth trees rose around the trail and its hewn guide fence. Cicadas and birdsong clashed with the steady clop of hooves. Hansall led their expedition in companionable silence, his back an easy straight line used to the seat. Leslie looped his reins around the saddle knob, and the chestnut mare simply followed on. The last vestiges of his metropolitan life sloughed away as natural isolation arose.

Traversing the five-hundred-mile stretch between his northern city and a counties assignment transformed Leslie into a simpler thing, someone whose worries were limited to saddle-soreness and the pinch three centimeters beneath the shrapnel scar on his thigh—either nerve damage or a metal sliver. The nursing service patch on his jacket emptied his body of its contrary desires and replaced them with a set of tasks: no longer a person, but a purpose. Survival was simpler that way.

Light slanted through the canopy at strange low angles, and toads began to croak from the shadows. Suddenly aware of encroaching night, Leslie asked, “How much further?”

“Maybe thirty, forty-five minutes,” Hansall said, unperturbed.

A brief time later they arrived at a fork in the trail and turned left. The path crested the belly of a hill then pitched downward, widening to funnel them into a protective holler. Underneath twilight stillness, water babbled over stones. Stands of oak and beech, sycamore and dense honeysuckle amplified the sound until it enfolded them. The orange sunset burned on the horizon through a break in the foliage and fireflies dazzled in the air.

Leslie kneed his mare to trot up alongside Hansall’s. The gloom appointed both their faces with carnival masques of shadow. Hansall gestured ahead, his no-doubt-welcoming smile reduced to a slash of teeth.

“That’ll be us through the clearing,” he said.

The nape of Leslie’s neck crawled. He slapped at it and his palm came away smeared with the corpse of a fat black spider. His thighs clamped, but the mare ignored him; he wiped the remains on her flank. Unease wriggled its nasty legs around inside him. Somehow, despite all his years in one form of service or another, Leslie never noticed the boundary for too late to turn back now until he’d already gone and crossed it.

The trail mouth spat them out right on Spar Creek’s doorstep.

The town filled a bowl made by three steep, converging hills. Dual rows of clapboard buildings flanked the dirt-and-shale center lane. Farther down stood the church, homesteads with sleeping dogs on their porches, one large barn, and a schoolhouse. Beaten grass paths led into the night, ranging toward fields, animal pens, cabins and maple shacks and hunting blinds. The distant sound of workmen singing—part cow’s bellow, part melodic shout—floated on the air. Leslie wheeled his horse to a stop. Light glowed behind thin curtains in all the breeze-gapped windows. One matronly woman cast them a blank glance while locking her shopfront, but otherwise the lane stayed empty. A frontier nurse’s arrival usually provoked far more curiosity.

“We’ll be putting you up in our back cabin,” Hansall told Leslie. “Sarah should have it all readied.”

“Thank you,” he said.

They rode on past the general store and a smattering of homes. Near the community barn, drying tobacco scented the air. A two-horse cart with lanterns hung fore and aft bounced up the perpendicular trailhead, stacked with fresh leaves to be hung. Four men on the cusp of adulthood walked alongside. The leading pair were clearly related, both towheaded and farm-stock broad. The two lagging behind were just as clearly not: one barrel-chested and bald-shaven aside from his ginger beard, the other wiry-slight with a gathered knot of long dark hair. The youthful softness of his cheeks was offset by a flat and flinty scowl, which caught on Leslie then flinched aside. Leslie fought the urge to raise an eyebrow.

One of the blonds hollered, “Home again, Jackson?”

“Home again, and with a nurse to show for it!” he replied.

Leslie waved off their hellos—as well as their notice of his riding trousers, his army boots and cap—but Hansall didn’t pause, so they cantered on away.

“Who’s the kid with the attitude?” Leslie asked.

“Oh, that’d be our Stevie Mattingly,” he said in a tone of tolerant amusement.

Several yards past the main thoroughfare, nestled in a copse of trees, sat a yellow-painted house with its own well, outhouse, barn, and back cabin. Hansall swung down from the rented horse and walked her across the lawn to the front post. He had built himself a comfortable life down a coal chute drawing lifeblood out of the hills, and it showed on his well-appointed land. Leslie scrubbed a thumb over his teeth, clearing grit from the ride, and hitched his mare as well. The front door opened on a woman wearing a brown skirt and white shirt belted at the waist. Her long, sandy hair hung loose.

“Sarah, meet Miss Bruin,” Hansall said.

“Pleased to meet you,” Sarah replied coolly.

“Would you mind showing her back to the cabin while I get the horses in?”

“Of course.”

Leslie dipped a bow as Sarah descended from the porch. Bare feet and ankles flashed beneath her hemline. With his travel pack swung over one shoulder, Leslie followed her around the backside of the house. The westernmost hill swallowed the lingering sun and night spilled across the holler.

Sarah pointed him to the cabin. “There’s a washbasin ready for you, and leftovers from dinner. We share the same outhouse. Knock on the back door if you’re needful.”

“Thank you—” Leslie began.

Sarah turned heel and strode away.

A handsome married woman giving him the cold shoulder wasn’t entirely a surprise. He muttered, “Well, all right.”

The single-room cabin contained an iron stove with a pipe through the roof; a brass bedframe topped by mattress, quilt, and pillow; a desk with water basin and lantern; a scuffed cedar cabinet; and a swinging pane-glass window, left open. Moths fluttered around the lantern. Lowering the latch behind him, he unfastened his boots then stripped to boxers and undershirt. Muggy night air meant mosquitoes, so with a groan he swung the window shut. He had a number of interlocking tasks he’d need to start first thing on the morrow: secure a location to run services from, determine the receptivity of the townspeople to nursing, count the children and pregnant or aiming-to-be-pregnant women, diagnose any parasitic infections or other health troubles, and ultimately establish himself as an authority … but never too much of an authority, lest the local doctors or aunties sense a threat to their monopolies.

And lastly, though the FNS would turf him if word got ’round, he had to keep an eye peeled for those secret, vital needs. Wives tired of childbearing but unfamiliar with preventatives; young men clueless on how to please their paramours; girls whose bodily education began and ended in the church pew; fellows who weren’t quite fellows, and ladies who weren’t quite ladies: once he’d integrated into town life, the whispers would start to arrive at his ear, and he could apply the sexological knowledge he’d gathered in Europe. He’d grown proficient at pursuing his own crosswise labors from within the troubled system he served; that was the real reason he’d stuffed himself back into a nurse’s role. In the meantime, he collapsed onto the creaking mattress and drew a book from his pack. Orlando: A Biography, which he’d secured from a city shop during his preparations for Spar Creek. Novels had always supplied him with the comfort, understanding, and indulgence life otherwise lacked. Swaddled by fantasies of being elsewhere or else-when, plied with a woman’s tender kisses and safe from harm—during those psychic travels he could be free, and desirable, and whole. Thumbing to his dogear, he read, Nature, who has played so many queer tricks upon us, making us so unequally of clay and diamonds …

A tree limb cracked like gunfire, too close for comfort. Leslie smacked the book closed and shot bolt upright. His reflection flickered in the window’s black glass, hollow-eyed and broad-shouldered, staring reproachfully. Though he sat rigid waiting for another noise, none came, aside from the distant creek murmuring through the eaves.

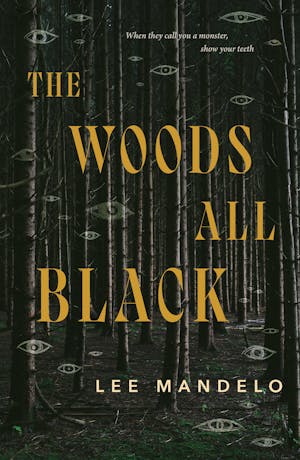

Copyright © 2024 by Lee Mandelo