1A POINT THAT EVERYONE SHOULD CONSIDER CAREFULLY

They met in secret. They met outside the presence of the executive board and without even Martin Luther King Sr.’s knowledge. This was how King’s own son, Martin Luther King Jr., wanted it. Only a few people, the absolutely necessary ones, were to be invited to the two-day retreat outside Savannah where the most dangerous idea of the civil rights movement would be discussed.

It’s unclear how many showed. The number is somewhere between eleven and fifteen. Accounts vary due in part to the secrecy of the conference and the egos of those in the movement. The attendees were Southern Baptists, and Christians, like anyone else—and maybe more than anyone else—want to be among the chosen few, especially when posterity asks, Were you there? What we do know is that the majority of those anointed arrived in Savannah that January morning in 1963 by jet or train, coming from all over the country, and headed now, by various cars, through a piney coastal Georgia until they reached a clearing some thirty miles south, the Dorchester Academy, in Midway. The academy spread across 105 quiet and shaded acres, manicured and expansive, and on the estate rose eight simple buildings, the mark of the academy’s history and its ongoing ambition. It began in 1871 as a one-room schoolhouse for freed slaves. It expanded to a larger school and then added a dormitory for all the Black people who ached to read. The academy built a credit union on the grounds in the 1930s to help Blacks buy homes and open businesses. By the 1960s Martin Luther King Jr.’s organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), used the estate to train hundreds of volunteers in King’s preferred form of civil disobedience, the nonviolent protest.

The majority of secret-meeting attendees on that clear but cool January morning had been to Dorchester before. They parked their cars and walked to the white-pillared brick dormitory without a newcomer’s sense of reverence. They had too much on their minds for awe. A grimness followed them and even matched their conservative suits. It lined their faces. They sensed what they were going to discuss.

They settled in one of the dormitory’s meeting rooms, where the humidity in the summer had cracked and peeled the paint off the beige walls, and huddled near one another in seats that faced the front of the room. King directed the proceedings, but the one who stood before them now was Wyatt Walker, the SCLC’s executive director. A tall northerner with a thin mustache and even thinner build—he looked at thirty-four like a malnourished, radicalized grad student—Walker commanded the room with his piercing gaze and flair for the dramatic. “The Madison Avenue streak in me,” he later said. From behind his big black-rimmed glasses he took in those assembled around him and told them they were about to embark on a campaign unlike any other.

“I call it Project X,” Walker said. Because X marked the spot of confrontation.

And confrontation because there had not been enough of it.

* * *

Walker discussed what he and so many of those present had just endured: the SCLC’s sustained civil rights campaign in Albany, Georgia, the year prior, in 1962. It had failed completely. It had failed for numerous reasons, Walker said, but one of them was that the nonviolence the SCLC favored and had learned from Gandhi’s success in India—assembling marchers and having them sit at the seat of white power, and then not move—needed to be met by violent white authority to work. When white authority in India or the American South used violence against peaceful protesters, their brutality called into question not only the acts of violence but also the authority figures’ rule of law. To question unfair rules was the first step, Gandhi and King found, to changing them. In Albany, Georgia, though, the bigoted but clever police chief, Laurie Pritchett, had read up on King and then Gandhi and realized he could deter these Black leaders by accommodating them. He told his force to put away their billy clubs. He told his force to arrest the marchers with unctuous care, especially when the bulbs of any news camera popped—cameras that hoped for a bloody spectacle, had even been promised one by King and Walker, but instead got images of Pritchett removing his hat and bowing his head, as if in prayer himself, before gently handcuffing the kneeling Black pastors at his feet. The news media grew restless and then hostile at how long the Albany campaign continued, off and on for eight months. When King and the SCLC lost the support of local protesters, they left town, humiliated.

Albany was “a devastating loss of face” for the movement, the New York Herald Tribune wrote. Perhaps “the most stunning defeat” of King’s career.

There had been many.

Failure followed the SCLC everywhere now. Walker and King knew it, and so did the rest of the SCLC’s leadership huddled in that beige room. The movement’s biggest success, the Montgomery bus boycott, had also been its first, and that was seven years ago. But thanks to the intransigence of the Alabama government and the fear of the Klan, Montgomery’s bus lines in 1963 were as segregated as they’d been in 1933. “Most Negroes,” one journalist noted, “have returned to the old custom of riding in the back of the bus.” The younger Black organizations, like the zealous Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), led by John Lewis, sensed the middle-aged King’s ineffectiveness and mocked him these days almost as ruthlessly as the southern press did. In Albany, a campaign initially staged by SNCC but usurped by King, SNCC and other organizers took to calling King “De Lawd”: the one who knew what was best for you. The mocking phrase played off King’s pomposity in dress and speech and sneered at who his sermons attracted: older crowds who would amen alongside King from the pews but wouldn’t take action on the streets. De Lawd didn’t give people agency. De Lawd preached because De Lawd refused to lead people away from the pulpit. “You are a phony,” one SNCC organizer telegrammed King.

The cynicism and infighting between the organizations of the civil rights movement reflected a broader frustration nearly all Black people in America felt. Nothing had improved. Brown v. Board of Education had become law in 1954, and yet in the nine intervening years virtually every school in the South remained segregated. Blacks everywhere earned 45 percent less than whites. In the South only 28 percent were registered to vote—and this after a giant registration drive by the Democratic Party in 1960. Even liberal President Kennedy had cooled on King and the civil rights movement. King wanted a second Emancipation Proclamation, a document that would update what Lincoln had written in 1863 and at last liberate Black people from Jim Crow. Kennedy had seemed enthused about the idea when King met with him at the White House in 1962. Kennedy had even asked King to write a draft of the document. King hoped that the president would deliver the speech on January 1, 1963, on the hundredth anniversary of the original Emancipation Proclamation. But after Kennedy received the draft prepared by King and the SCLC, the president and his administration stalled, returning the SCLC’s urgent messages days or weeks later. The hundredth anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation came and went, with segregation the law of the South and oppression felt everywhere else, too, and nary a word from Jack Kennedy about any of it.

So if America was going to change, Wyatt Walker said to the privileged few at Dorchester that January day, America had to be shocked into changing.

This was the point of Project X.

We need to go to Birmingham, Walker said.

* * *

Birmingham? Those assembled shifted uncomfortably in their seats. This was the bad news they’d feared. The people in that beige room had heard the joke about Birmingham:

One morning a Black man in Chicago wakes up and tells his wife that Jesus has come to him in his dream.

“Really?” she says.

“Yeah,” the man says. “Jesus told me to go to Birmingham.”

She’s horrified. “Did Jesus say he’d go with you?”

“No,” the man responds. “Jesus said he’d go as far as Memphis.”

Birmingham, Alabama, was not so much a city in 1963 as a site of domestic terror. It was known, sometimes gleefully, and by public officials, as “Bombingham.” More than fifty residences and Black-owned businesses had been bombed since the end of World War II. Bombings were so frequent in one Black neighborhood that it was now called Dynamite Hill. These bombings went unsolved for the same reason cops routinely exercised their “rights” to shoot any Black “suspects” who turned their backs and fled. The force was overseen by Eugene “Bull” Connor, a virulent racist and public safety commissioner with barely cloaked ties to the Ku Klux Klan. The point of Bull’s Birmingham—and make no mistake, Bull ran Birmingham—was fear. The police raped Black women. The Klan castrated Black men. The cops and klavern tapped the phones and, no doubt, bombed the houses of anyone who tried to improve the lives of the oppressed. Not long after President Kennedy’s inauguration, CBS’s Edward R. Murrow reported from Birmingham. The city had the reputation as the most segregated, most racist, most violent place in America. Murrow came to agree. Just before he left town, he told his producer he hadn’t seen anything like it since Nazi Germany.

That was Birmingham. And the city’s violence, its hatred, was also its appeal. Walker told the crowd at Dorchester that the SCLC needed to go to the very site of white terror and anger every terrible person there. In order for its nonviolence to work, the SCLC needed to subject itself to the full wrath of Birmingham, in the hope that white people outside the city might at last see, through the SCLC’s suffering, the plight of all Blacks in America. The SCLC needed, Walker said—and you can almost see him pacing the room at this point, part preacher, part professor, and all stringbean showman, those black-rimmed glasses accentuating his gauntness and erudition like some mystic from the Georgia pines—the SCLC needed to go to Birmingham to turn the city into a metaphor of the Black experience.

How to do that? How to show white America and the Kennedy brothers who governed it what it meant to be Black in America?

You have to escalate the situation, Walker said.

“Project X will have four stages,” he said, and here Walker handed out a blueprint among the assembled, eight typed pages that revealed his organizational prowess as executive director of King’s SCLC. The first stage, Walker said, involved mass meetings at night whose purpose would be to draw recruits to the sit-ins the SCLC would carry out by day. These sit-ins would be at the lunch counters of segregated restaurants in Birmingham and infuriate Bull Connor.

The second stage would call for a boycott of Birmingham’s downtown business district. Black people spent about $4 million a week downtown. They accounted for roughly 25 percent of the money spent in the city. The profit margins of those stores were small enough, Walker said, that if Black people didn’t spend there, white businesses couldn’t survive there.

The third stage would escalate from a boycott of downtown merchants to a mass protest of Birmingham itself, its segregation and racism. White people, Bull Connor especially, would be irate by this third stage, and the sea of Blacks protesting throughout the city would lead to mass arrests. Mass arrests would fill the jails. Filling the jails would further escalate the situation because the optics of crammed cells were the optics of success. They would inspire more people to join the movement, Walker said. And when the SCLC kept marching in spite of the mass arrests, Bull Connor would be confronted with a choice: allow these Black people to protest in his city, which would humiliate him, or suppress these Black people and turn his terrible vengeance on them, which would give the waiting press corps all the gory copy they needed.

Walker thought Connor would choose the latter. This would lead to the fourth stage of Project X.

Seeing grotesque images on the nightly news and in the pages of newspapers and newsweeklies would cause a furor across the nation and a not insubstantial number of people to descend on Birmingham itself, to protest alongside the SCLC and its brave volunteers. These justice-seeking tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands, millions, would march the streets and boycott the stores, Blacks and whites alike, and together they all would force Bull Connor and Birmingham City Hall—without options, without jail cells to put the marchers in or excuses to hide behind—to broker a fairer and more equitable future for Birmingham. Together they all would help the people of Birmingham in ways no one had before. Together they all would end segregation in the most racist of American cities.

And by ending segregation there—by X marking the spot—together they all would show they could end segregation anywhere.

That, Walker said, was why they had to go to Birmingham.

* * *

King loved it. Positioned among the dozen or so at Dorchester, King thought Project X showed why Walker had “one of the keenest minds” in the movement. Project X escalated tension as it expanded its ambition. The plan was not unlike Walker himself. In the three years he’d been SCLC’s executive director, Walker had made many staffers cry from his punctilious demands, but he had also transformed the SCLC from a fallow nonprofit with tax problems into a respected organization. King heard all the time from the ever-growing body of staffers how bossy and unbearable Walker was. Walker was bossy and unbearable. That ever-growing body also proved his worth. Walker breathed life into King’s organization, gave it strength. The fastidious accounts he kept reflected the dream Walker and King shared, and had always shared, since they’d met more than a decade earlier as grad students at an inter-seminary conference, both of them presidents of their respective seminary classes. They had planned to use their education to serve God and Blacks in the segregated South. When King in 1960 asked Walker to quit his pastorship in Virginia and join the SCLC, King knew he was getting more than a bookkeeper. King was getting a publicist, one who’d been born in Massachusetts and understood the northern press—could even mimic the nasal northern cynicism with which the reporters at national outlets talked. In Walker, King was also getting a hard-ass, a Bobby Kennedy to King’s Jack, a man who by his own admission would “alter my morality for the sake of getting a job done.” Above all, King was getting an optimist in Wyatt Walker, someone who, like King, saw beyond the gray and bleak present into a southern future that no longer noticed color. Project X, moments after the presentation, was already vintage Walker: a grand vision, a precise and even ruthless means of achieving it, and the potential for a lasting and epoch-defining victory.

There was little discussion of it. That was the shocking thing. It seemed ingenious, and it was all there, on those eight meticulous pages. The pages forced the assembled into contemplation and perhaps cowed them into silence, but Walker’s plan was so thorough, so epic in its implications, that many at Dorchester simply wanted to believe in it.

The group that day altered nothing of Walker’s blueprint.

* * *

James Bevel was perhaps the lone person who saw that as a problem. As the talks proceeded and then exhausted themselves, as the assembled prayed about Walker’s plan and then discussed it again, Bevel kept wondering why no senior executive of the SCLC—not Stanley Levison, the most liberal member of the secret caucus; not Andrew Young, the most conservative; not Dorothy Cotton, the lone woman; not Fred Shuttlesworth, the lone Birminghamian; not Ralph Abernathy, King’s best friend; and not King himself—would state what seemed obvious to Bevel: that Walker’s arrogance had infected his plan and corroded the SCLC.

Bevel was one of the youngest at Dorchester, a twentysomething who had the kind of reputation that took other men a lifetime to achieve. In 1960 Bevel had co-led massive sit-ins alongside SNCC at Nashville lunch counters. During one sit-in, the merchant had fled his store but locked the doors behind him, trapping the Black protesters inside and then gassing the place, literally fumigating it with insect repellent while the protesters gagged and choked on the poison. Just as people passed out, Nashville firefighters arrived, breaking windows and saving lives.

Bevel responded by continuing the protests.

That kind of militant fearlessness inspired John Lewis and the rest of SNCC. Bevel was a touch older than the college students of SNCC but as righteously committed to justice, and his alliance with Lewis eventually attracted Martin Luther King Jr. King saw in Bevel the revolutionary his own organization needed, and recruited him to the more middle-aged SCLC. If Bevel heard cries of betrayal from his SNCC friends, he ignored them. Bevel was his own man. A young preacher who wore overalls instead of pastoral robes because country bibs bore no airs in his native Mississippi. A student of God who placed a yarmulke on his shaved head each day because Old Testament prophets like Ezekiel inspired him. Their strength summoned his own. Bevel had a strange power: to be young and of this fraught moment in the 1960s and yet wizened and even, somehow, ancient. He pushed for a new dawn that many Black people were uncomfortable with while using the language of the Torah to do it: “Thus saith the Lord,” said James Bevel. He was twenty-seven but seemed as if he’d always existed. Many in the movement called him “The Prophet.”

By that January day at Dorchester in 1963, he carried a somewhat redundant title within the SCLC: the director of direct action. It meant Bevel was the operations man, the one who took the vision and manifested it. Looking at Birmingham through an operational lens, Bevel saw the classic flaws of the modern SCLC.

Walker’s Birmingham plan assumed too much, he said. It assumed Black people in a city run by fear would subject themselves to the worst impulses of the white authority that oppressed them simply because Martin Luther King Jr. asked them to at nightly mass meetings. It assumed hundreds if not thousands of people would be inspired rather than frightened by a few jailed Black brethren, and would rush to be thrown into similar dank cells for the movement. It assumed, mostly, what the SCLC assumed in Albany and had always assumed: that a hierarchical top-down strategy would inspire people from the bottom up. This was the fault of King and staid vestigial thinking from the 1950s, Bevel said, but it was mostly the fault of Wyatt Walker. The executive director who loved his title. The one whose arrogance coursed through the organization until every staffer lost his own humility. The one whose grand plan in Birmingham patronized the very people it meant to serve.

Bevel snickered at the blueprint in his hands. He couldn’t believe that Wyatt Walker really believed that Birminghamians had no notion of a less-suffocating life until Walker scrawled his X on their city. Did Walker think they hadn’t fought to integrate? One year before, in 1962, the courts had at last ruled Blacks could stroll across the same parks and golf courses as whites in Birmingham. How had Bull Connor responded? He’d shut down all city parks. He’d shut down all municipal golf courses. That was Birmingham, Bevel said, the unrelenting totality of its suppression: Even if they kept to themselves, Blacks and whites could not share the same square mile of public space. And—what?—Wyatt Walker was going to change Bull’s thinking by force, when a U.S. district court hadn’t by decree? Or richer still: Wyatt Walker was going to change Black people’s thinking by dint of a four-stage plan that escalated tension? Poor Black people of the Deep South, not unlike the sort Bevel had known in his hometown, Itta Bena, Mississippi: rustic, conservative, and proud of whatever they’d clawed from the white devil? And here came light-skinned Wyatt Walker with his graduate degree and club ties telling these Black Birminghamians, No no! You’ve been fighting the wrong way; I know better. And they were supposed to follow that man? That man who, even when he dressed down, as he did at Dorchester, ironed a crease into his blue jeans? That man whose own well-off preacher daddy had read every day in Hebrew and Greek while so many Black adults in Birmingham had parents who could not read at all?

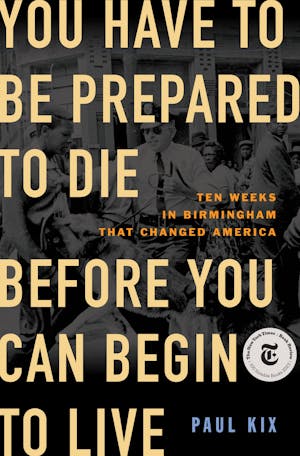

Copyright © 2023 by Paul Kix