I.

Everyone’s got a pithy quip about history. “History is the autobiography of a madman,” wrote the Russian socialist Alexander Herzen. Arnold Toynbee, British historian, complained about “the dogma that History is just ‘one damned thing after another,’” while James Joyce wrote, “History is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake.”

These are pretty good, but Jane Austen, as was her wont, came closest to the truth when one of her characters sums history up as “the quarrels of popes and kings, with wars or pestilences, in every page; the men all so good for nothing, and hardly any women at all”; she adds, “it is very tiresome.”

Whatever else history is, most people would agree that it is an account of things that happened. There’s an old joke that runs: Two men in a bar are watching a televised baseball game. One man bets the other a sawbuck that the visiting team will win. Sure enough, the home team’s outfielder drops a fly ball, and the game ends with the visitors’ victory; but when it comes time to collect the man says, “You know what? I feel too guilty to take your money. They’re airing a game from this morning, and I saw it live. I already knew who would win.”

The second man says, “I saw the game this morning, too. I just thought for sure this time he’d catch that fly.”

Whatever that is, that’s not history.

II.

Paul Rée is most famous now for being friends with Friedrich Nietzsche—Nietzsche had so few friends that all of them are at least a little bit famous—but in the nineteenth century he was known as a philosopher in his own right. How many friends Paul Rée had is open to debate, because Rée had the annoying habit of going around Europe trying to persuade people they had no free will. No one likes to hear that. People inevitably responded to Rée’s claim by saying, “Look, look, I can do whatever I want,” and demonstrated their freedom by raising their right arms, always their right arms, to prove their will was free; once Rée spoke to a left-handed man, and he, for a change lifted his left. Rée was unimpressed.

Rée espoused a deterministic view of the world, a view that was somewhat in vogue among depressive cynics of the time. Mark Twain, case par excellence, famously said: “The first act of that first atom led to the second act of that first atom, and so on down through the succeeding ages of all life, until, if the steps could be traced, it would be shown that the first act of that first atom has led inevitably to the act of my standing here in my dressing-gown at this instant talking to you.”

I am free to lift my arm, if I will it. But am I free to will it? Philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer (whom Rée had read) pointed out decades earlier that you are free to put a gun to your head and pull the trigger, if you wish to—but it’s a rare man who would do it just to prove he was free!

III.

Don’t worry about Rée. Just play along for a moment.

Play along as we imagine a coin flip.

When we say a coin flip has a 50% chance of coming up heads, we don’t mean it for any one particular flip. Any one flip has either a 100% chance of coming up heads or a 0% chance of coming up heads; we just don’t know which one it’ll be. Flip a coin a hundred times and about half of those flips will be heads; that’s what the 50% means. “Call it in the air!” A hypothetical alien superintelligence capable of perceiving 1. the force with which the coin was propelled upward, 2. the speed of rotation, 3. the wind resistance, 4. the balance of the coin, 5. etc., could tell you, before the coin fell, whether it would be heads or tails. In a Rée/Twain universe, a really impressive alien superintelligence could determine, based on your genetic makeup and every stimulus you’d ever received from conception on, including the exact environment you are in right now, precisely how you would flip, and therefore what the result would be, before you even flipped it.

No such superintelligence presents itself, but our limited brains can perceive the result of its experiment. If the coin comes up heads, you were going to flip it heads. If the coin comes up tails, you were going to flip it tails.

“I could have flipped it differently,” you say. But you didn’t.

Rée would say you couldn’t’ve.

IV.

Arthur Schopenhauer was an interesting fellow. He followed the same precise, self-imposed schedule every day, which included five hours of writing, half an hour of flute practice, and a two-hour walk—regardless of the weather—around Frankfurt. He was one of the world’s biggest jerks, and once pushed an old lady down the stairs for making too much noise. He believed the highest virtue was lying down, doing nothing until you starved to death (which of course he never attempted). He enjoyed being miserable perhaps more than any other human being in history, even compared to other nineteenth-century Germans. His famous mental exercise to prove that there is more suffering than joy in the world runs like this: Imagine two animals, one eating the other; imagine the joy of the eater; imagine the suffering of the eaten; which is greater?

Schopenhauer published his magnum opus, The World as Will and Representation, at the age of thirty and declared the book to be the absolute answer to all philosophical riddles, insisting that the Holy Spirit had “dictated” parts of it; no one noticed, and he languished in obscurity for years. His mother was a popular novelist, and Schopenhauer seethed with jealousy over her success. When he yelled at her that his book would be available long after hers had been forgotten, she replied that, yes, his book’s entire print run would still be available.

A great zing, but it turns out that Arthur Schopenhauer was right, which is why we’re not citing The Aunt and the Niece by Johanna Schopenhauer, and neither is anyone else. Arthur Schopenhauer became famous eventually, in part because he won a contest. In 1838 the Norwegian Scientific Society offered a prize for the best essay on the freedom of the will. Schopenhauer’s entry won, and it was very nearly the first time anyone had read something he’d written. Schopenhauer later published his “prize essay” bundled with another essay, written for another contest, which lost even though it was the only entry.

People would tell Rée: Sure, I lifted my right arm, as everyone does, but I could have done something different. And this is what Schopenhauer pounces on. In the winning essay, “On the Freedom of the Will,” he compares could have done to still water, which may insist it can rise in great waves (as it does in a storm) and can turn into steam (as it does over a fire) and can course rapidly (as it does downhill)—but is currently choosing to stay calm and placid. Thus wills the pond!

Because if we could have done something different from what we’ve done, why has no one in the history of the world ever done it? If I claimed to be able to levitate even though I had never done so, everyone would laugh at me; and yet we accept the alleged power to deviate from our actions sight unseen.

You say you could have flipped the coin differently, and yet you never have. You never have because you couldn’t’ve. This is a book about couldn’t’ve.

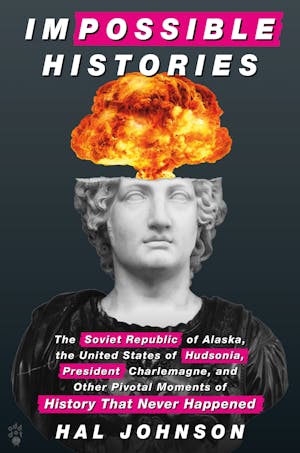

This is a book about things that could never happen. We know that because they didn’t.

V.

What if, we ask ourselves, what if Napoleon had not invaded Russia, but rather had gathered his troops and invaded England? We never ask ourselves: What if Emily Dickinson gathered troops and invaded England? It seems absurd to imagine Dickinson organizing such an expedition, but in fact an Empress Emily marching into London is just as likely as an Emperor Napoleon marching into London. Both are 100% impossible.

No one knew, in 1803, that Napoleon’s invasion of England was impossible, of course. It worried a lot of people, whereas Emily Dickinson would not be born for another twenty-seven years, and provoked no terror among the British people even after she began existing. Perhaps Napoleon’s invasion was impossible because the British had too much naval experience, or perhaps Napoleon’s invasion was impossible because the general was simply a better tactician on land than he was at sea. If things had been different, the invasion would not have been impossible—if 1. Napoleon was a naval genius, for example, or if 2. a meteor had struck London, or if 3. all British naval vessels had spontaneously turned into piles of dry leaves, rendering them defenseless. But things were not different, and all three possibilities were, it turned out, equally unlikely. It’s just that the British knew 3. was impossible, and never worried about it; and knew 2. was unlikely, and never worried about it; and so they fretted about 1. We imagine ourselves in their position, and we imagine a different Napoleon, or a freak storm destroying the English fleet, or a series of lucky naval battles giving the French control of the Channel. But it’s no more likely to have happened than a martial, power-mad Emily Dickinson. It would require a different Napoleon, or a different world.

VI.

The first thing that happened was that a meteor hit the earth and wiped out the dinosaurs.

Copyright © 2023 by Hal Johnson