Burrowing Owl, 606 W. 145th St., Sugar Hill, Harlem, muralist: Jana Liptak

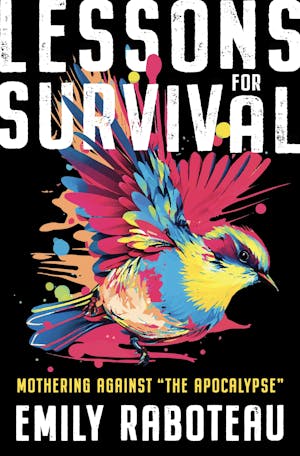

SPARK BIRD

If I can be called a bird-watcher, my spark was a pair of burrowing owls, painted on the narrow storefront gate of a shuttered real estate business on 145th Street, in Harlem, that brokers single-room-occupancy housing for two hundred dollars a week. I spotted them after ice-skating with one of my kids, at the rink in the shadow of towering smokestacks at Riverbank State Park, a concession to our community for the massive wastewater treatment plant hidden beneath it. It was midway through the Trump years: January, but not cold like Januaries when I was little, not cold enough to see your breath. It wasn’t snowing, and it wasn’t going to snow. The owls watched me quizzically, with their heads cocked, their long, skinny legs perched on the colored bands of a psychedelic rainbow that seemed to lead off that gray street into another, more magical realm.

Among people who watch birds, it’s often the case that a first bird love, the so-called “spark bird,” draws them forever down the bright and rambling path of birding. For Aimee, it was the peacocks in her grandmother’s backyard in southern India. For Kerri, it was a whooper swan above Inch Island, in County Donegal, the year the peace process began. For Windhorse, it was the Baltimore orioles flitting about in the high branches of poplars at his grandfather’s house up north, on the lake. For Meera, it was the red-winged blackbird, there at the feeder, when she was small. Her mom told her the name, and it all clicked into place—black bird, red wings—as she learned the game of language and how we match it to the world around us.

I pointed out the extraordinary owls to my kid, stopping to take a picture with the camera on my phone.

“Look,” I said.

“I want hot cocoa,” my kid replied.

We turned the corner and made our way up Broadway toward the Chipped Cup for overpriced Belgian hot chocolate. On the corner of 149th, I spotted another bird, the American redstart. It was painted on the security gate of Washington Heights Pediatrics—the kind of doctor’s office that struggles to keep the lights on with trifling Medicaid payments and nebulizes asthmatic Black and brown kids, like mine, with albuterol when their lungs constrict too severely for a pump to clear at home. The tuck of color under its wing matched my kid’s unnecessary winter hat. I took another picture. Oh, New York—you gorgeous aviary of madcap design! Across the street, from the corner of my eye, I saw more: a pair of Calliope hummingbirds painted mid-flight outside the Apollo Pharmacy.

That’s when I understood there was a pattern.

Calliope Hummingbird, 3659 Broadway, Sugar Hill, Harlem, muralist: Kristy McCarthy

After the spark, I started noticing scores of them along my two-mile walk to work at City College. Most of the bird murals in Upper Manhattan are spray-painted on the rolled-down security gates of mom-and-pop shops along the gallery of Broadway, at street level. Others are painted up higher, on the sides of six-story apartment buildings. They nest, perch, and roost in the doorways of delis, pharmacies, and barbershops. Lewis’s woodpecker at the taqueria, the almighty boat-tailed grackle at the Buena Vista Vision Center, Brewer’s blackbird at La Estrella Dry Cleaners, and so on—there are dozens of bird murals, each one marked in a corner with the name of the ongoing series to which they belong: the Audubon Mural Project.

John James Audubon, the pioneering ornithologist and bird artist, once lived in the hood. He’s buried in the cemetery of Trinity Church, at 155th Street, midway between my apartment building in Washington Heights and my job in Sugar Hill, Harlem, where I teach writing, sometimes using Wallace Stevens’s “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird” as a prompt. Audubon Terrace, once part of his estate, is now the site of a complex of cultural buildings. Other uptown locales named after Audubon include a housing project, an avenue, and the ballroom where Malcolm X was assassinated. Its historic facade remains as cladding to a newer medical research building—a concession to Black Americans who protested the ballroom’s demolition—at 165th Street, across from the emergency room of a New York–Presbyterian hospital. When you walk by these places, as I do, you can spy many of the same birds Audubon chronicled in his masterful archetype of wildlife illustration, Birds of America (1827–1838), in the guise of public art.

The project is an unfolding environmental awareness partnership among the gallerist Avi Gitler, the National Audubon Society, and local business and property owners. The murals are sponsored through donations to Audubon and painted by myriad artists, some of them local, in a diverse range of styles. Uptown, there are presently 123, and counting, bird species depicted. (Sometimes they disappear when businesses change hands.) The project aims to reach 389. This is the number of North American species, according to Audubon’s 2019 “Survival by Degrees” report on birds and climate, at risk of extinction from climate change—an alarming two-thirds of North American birds. I have attempted, so far, to photograph them all. The world is changing faster than we can. The changes are restructuring our lives in ways we struggle to respond to, birds and humans alike. How do we navigate this shifting terrain?

A printable map on the Audubon Society’s website indicates the address of each mural. I prefer not to use that resource as a guide; I like the element of surprise. As with actual birders, I never know which birds I’ll see on a walk. Sometimes a new bird appears to have landed overnight. Older birds may be marked with graffiti or sullied by weather and grime. I was saddened to discover from the window of the M4 bus, while riding downtown, that someone had spray-painted over the tundra swan I’d come to love with a cloudy white cipher of bubble letters. Who did that? I wondered, thinking of that rogue graffiti artist known as Spit in the 1984 hip-hop movie Beat Street, who defaced the work of other artists by tagging over it.

I felt glad to have documented the tundra swan before it disappeared. If temperatures rise three degrees Celsius, 93 percent of this bird’s breeding habitat in the tundra of far northern Canada is projected to be lost. Because the Arctic is warming faster than anywhere else on the planet, tundra swans have nowhere farther north to go.

Tundra Swan, 3631 Broadway, Washington Heights, Manhattan, muralist: Boy Kong

As a photographer, I am drawn to the visual echoes between the fashion and the feathers, the postures of people and wildlife: for example, the sweep of a dark trench coat that seems to give motion to the peregrine falcon’s wings, or the pair of black track pants that have merged with the legs of the glossy ibis so that the young man wearing them appears to be riding the bird. I wish to document the tensions among human, bird, art, and commercial signage. Sometimes the artists play with these elements, too, as with Snoeman’s mural of a Canada goose, wherein the bird beneath the canopy of a shoe store is styled in a pair of Timberland boots.

Canada Goose, 3868 Broadway, Washington Heights, Manhattan, muralist: Snoeman

I understand the project has landed in this neighborhood because of its connection to Audubon, and also because of the millions of endangered birds that migrate above Manhattan and continue to nest within it. I also appreciate its potential for helping connect a low-income community of color to the green sector, which is predominantly white.

Amelia Earhart is quoted in the mural at Manuel’s Grocery, at 152nd Street: “No borders, just horizons. Only freedom.” The bright yellow breast of the mangrove cuckoo pictured there matches the tank of the blowtorch in the hand of the plumber passing by. That bird is described as “a rare bird native to the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, and Florida in the U.S.” Unlike nations preoccupied with immigration, the artist states, “Birds See No Borders.”

I love these birds for their beauty, the way birders love actual birds, for the exalted brushstrokes of their wingspans that lift us from the drudge of survival. Some birds are reclusive: for example, the Florida scrub-jay and Mexican jay have long been trapped behind a hunter-green construction fence. The birds on buildings under scaffolding look caged. At businesses that struggle to pay escalating rents by staying open for twelve hours a day, seven days a week, the birds can be seen only at night, when the gates come down. At shops that have closed and not yet reopened, like the beauty salon with the laughing gull, the bird is always there.

Laughing Gull, 1728 Amsterdam Ave., Sugar Hill, Harlem, muralist: Simon Aredondo

“We know that the fate of birds and people are intertwined,” Audubon magazine editor Jennifer Bogo, wrote me. “That’s especially true in communities, like northern Manhattan, that suffer disproportionately from environmental and human health burdens. We hope that the Audubon Mural Project makes people literally stop in the streets and consider what’s at stake with this critically important planetary crisis, while at the same time beautifying and drawing attention to neighborhoods that have historically not been the focus of environmental protections.”

To my eye, the project is at once a meditation on impermanence, seeing, climate change, environmental justice, habitat loss and a sly commentary on gentrification, as many of the working-class passersby are being pushed out of the hood, in a migratory pattern that signals endangerment. Most of all, the murals bring me wonder and delight. I can hardly be called a bird-watcher. But because this flock has landed where I live, work, parent, pray, vote, and play, permit me to be your guide.

Peregrine Falcon, 752 St. Nicholas Ave., Sugar Hill, Harlem, muralist: Damien Mitchell

Glossy Ibis, 3671 Broadway, Washington Heights, Manhattan, muralists: Kristy McCarthy and Pelumi Adegawa

2021

Caution, N. Moore St. and Hudson St., TriBeCa, Manhattan, artist: Dee Dee Was Here

CAUTION

I needed the birds because I was in pain. When did I start feeling the pain? I think it was when our republic elected the demagogue and hope went missing. I remember the presidential debate: she, in her white pantsuit; he, pacing behind her like a menacing ape. The familiarity of that dance. He’s going to hit her, I thought. I clenched my shoulders. In the years I am talking about, 2016–2020, they remained clenched.

“My God,” my husband marveled when the election was called. “America really hates women.” I had told our two kids at bedtime that in the morning they’d wake to our country’s first female president. “You lied to us!” the five-year-old cried at breakfast, betrayed.

The election inspired a feeling of heartbreak bordering on insanity, which I dared not reveal to my family lest my family lose hope, too. For the most part, I carried the grief alone. On occasion, I vented to girlfriends, who got it. Angie gave me her copy of The Body Keeps the Score. Our autonomic nervous systems were all riled up. We were inflamed. The external calamity, which was political, coincided with the internal calamity, which was personal. My country, my body: broken. Me, too, the women said.

I looked all over the city for relief, not yet noticing the birds. My journey began with a chiropractor on the Upper West Side. Before he cracked my neck, the chiropractor told me I had an atlas tilt at the top of my cervical spine: the weight of the world on my shoulders. It was unclear to me whether the atlas could be manipulated back into place on its axis.

Ori Mi Pe, the classic Adire cloth indigo design, literally translates as “my head is correct.” In Yoruba belief, the head is the seat of personal destiny. Therefore, Ori Mi Pe means, “I will have a good destiny.” But my head was not correct. The junction of my skull and spine was off, the nerve center misfiring in that cathedral of delicate bones. I wondered what this meant about my destiny.

“Cervix” refers to the neck, or any necklike part, especially the constricted lower end of the uterus.

When he was deep inside me, my lover, my predator, claimed that he could feel my cervix. What did it matter that the abuse was years in the past, well beyond any statute of limitations—back when a hit song on the radio was “Survivor,” by Destiny’s Child; back in the days when I sat in a Survivors Anonymous peer support group of other women with PTSD in a church basement in Brooklyn—when it felt like the violence was happening all over again, right now?

“Do you feel guilty?” asked the primary care physician before referring me to a psychotherapist. I was already seeing a therapist on One Hundredth Street and Central Park West, who’d insisted on blood work and recommended bringing my husband to vouch for the truth of my pain, since doctors, as a general rule, disbelieve women. My husband was busy. I was busier than him by far, and on top of that, I was sick. The blood test could not explain why my hair was falling out. Thyroid, endocrine system, hormones: all were in normal range. And yet, I could barely get out of bed.

I wasn’t free to stay in bed. Duty called. My children needed food and feeding, washing, cuddles, stories, protection from the incessant evil messaging of white folks, and lotion on their ashy knees. My students needed feedback, mentoring, encouragement, recommendation letters, and advice on handling the sexual advances of their male professors. My health insurance needed explanations. My spine was either the sum of my moods, a barometer of the era, or a vertical timeline of historical abuse.

The orthopedic surgeon barely glanced at the X-rays before accusing me of being a boring patient. “You must have a lot of time on your hands,” he said, dismissing my symptoms, “to be worrying over nothing.”

The pain, he implied, was all in my head.

I did not have a lot of time on my hands. I had next to no time to myself, practically none at all. But it felt as though I’d been in a car crash. I am the backbone of my family, I wanted to tell him, how dare you speak to me like that; I am the backbone of my community. I birthed two babies at home without drugs because I trusted my own body to be a mammal more than I trusted in a healthy outcome from the medical machine. I am an educated woman suffering private heartache under a dictatorship.

These trips to doctors were fitted between trips with the children to the playground; to the Bronx Zoo; to Coney Island; to their barber, José; to the American Museum of Natural History; to the New York Aquarium; to the public library; to church; to their grandmother’s house in Queens; to the pediatrician; to the apple orchard upstate; back to the public library; back to the playground; and to the Little Red Lighthouse beneath the George Washington Bridge.

The symptoms radiating down my nervous system like falling dominoes included brain fog, tension headaches, jaw pain, limited head rotation, stiff neck, shoulder pain, tennis elbow, carpal tunnel syndrome, pelvic asymmetry, asthma, protrusion of discs, chronically cold hands and feet, low blood pressure, low self-confidence, paranoia, chronic diarrhea, despair, and fatigue. Worst of all, I could no longer hold up my head.

The dentist said I was like the princess and the pea. My teeth conveyed no rationale for the throbbing pain in my jaw. He accused my mouth of having perfect teeth but nevertheless referred me to an oral surgeon with a bad bedside manner. I told him I couldn’t sleep. We were on Eighty-Sixth Street, near the site of Seneca Village, where two hundred years ago a thriving Black enclave was displaced by the city through eminent domain to make Central Park.

You’re like the princess and the pea, the oral surgeon said, with the same disdain as the dentist. The two of them were in a private club; they shared a language, a philosophy predicated on the put-down. Neither man would prescribe painkillers. In spite of my straight, white teeth, they suspected that I was an addict hustling for opiates, that my mouth was a den of lies. I didn’t want painkillers. I wanted the pain to end.

Copyright © 2024 by Emily Raboteau