2:27 p.m. Sunday.

The diner is packed. Not surprising. It’s off a long stretch of the 5. Lots of campers. Families heading out to hike or visit relatives. There isn’t a big city for hundreds of hundreds of miles in any direction. Even fewer places to grab breakfast. All of the booths are taken, so after I push through the glass door connected to the motel lobby, I slide into a seat at the end of the counter. Glance up at the TV.

And wait.

I ignore the din. The sound of joyful voices. The scraping of utensils on plates.

I wait.

A waitress sidles up to me. “Good afternoon, honey,” she says, her voice thick. There’s a little twang in it.

I glance at her. Brunette hair, a nice orange hue in her lipstick. She smiles.

I point to the TV. It’s a rerun of some old sitcom I vaguely recognize. “Is that on channel 19?”

She looks to where I gesture. “I don’t think so. Why? You want me to change it?”

I nod. Press my left hand against the front pocket of my jeans, feel the few folded bills in there. “And I’ll take an orange juice. And a side of waffles. Extra syrup.”

She drifts away for a moment, then returns with a remote. Flips a few channels, then drops the remote next to me. “I’ll be right back with that OJ,” she says, then winks.

I wait for the cartoon to switch over to a commercial. I don’t prefer this, but I don’t have consistent access to a smart phone or a computer.

So I wait.

My heart thumps as the animation fades to black.

There’s an off-white clock hanging over the door I came through. I twist round, glance at it.

2:30 p.m.

The music swells, and even amidst the countless conversations around me, I recognize every note, every beat of the drum, every wordless harmony sung as the words appear on the screen:

CHRIST’S DOMINION

WITH DEACON THOMPSON

And then he’s there. On the screen. Deacon Thompson, his eyes always as blue as I remember them. He smiles.

I shiver.

There are five children surrounding him. I think it’s a good sign. He’s done so many broadcasts by himself lately. I scan quickly for any sign of her.

I see three kids with light brown skin, dark hair. A Black girl with her hair to her shoulders, straightened, her lips stretched open wide in a smile. An Asian boy beaming at the camera.

The children are close, almost as if they are vying to be on camera with Deacon.

And she’s not one of them.

I lean back. Heart sinks. Familiarity creeps in because … well, this is a rerun, too. I don’t hear the words Deacon says, though I can probably guess what they are. He’s talking about the children: how important they are. How he’s saving them. How broken the world is that week, with a long litany of sins.

And everything he and Christ’s Dominion have done to repair it.

I know he’s not reading from a script. I know that he probably means it all.

The waitress sets a glass of orange juice at my side. Lingers for a moment. I peer up at her.

“You know, I might just go to hell for saying this, but that Deacon guy is kinda cute.”

I don’t respond.

“You know, in a spiritual way, I guess.”

I nod at her, offer a weak smile. “Yeah, I guess.”

She shrugs. “And he wants to save the children! Put God back in our lives. Can’t say the same about most people.”

She doesn’t wait for me to respond before she heads to one of the booths.

I have gotten good at biting my tongue. At holding it in. I can’t say what I want to say because …

Well, she won’t believe me.

No one will.

But me, I don’t believe a word he says. Not anymore.

So I halfheartedly eat the waffles when they arrive, dousing them in syrup, knowing that they’re empty calories but they’re calories all the same. I only have twenty dollars in my pocket, and this will draw me back eight bucks. Nine with a tip. Not sure where I’m going to make more money, and the thought creeps back.

Maybe it’s time to leave.

The music swells again. I look up. Watch the number flash at the bottom of the screen, the one you’re supposed to call to give money to help all the children that Deacon is rescuing. Images flash forward: a toddler walking jerkily toward an adult couple. The kid has the same deep brown skin tone as me. Same black hair. His parents are pale and grinning and that’s the dream they sell you: Give us money. We’ll save them.

It changes. A group of kids—not one of them white—sit in a classroom. The classroom. Harriett Thompson—Deacon’s wife—is there, lecturing to them, and they nod, attentively.

And for a brief moment, my sister is on the screen.

She’s tall. Long black hair. Beaming with gratitude. In faith. I don’t know when this was recorded, though. It’s been hard to guess. Deacon’s show is broadcast over this tiny network throughout the week. It’s a recent thing, and most of these are the same as the ones that appear on his YouTube channel. His church … it’s all online. No place of worship. Just an online “movement.” So these videos are how he reaches people.

I think I’ve seen them all. Have most of them practically memorized. Maybe he’s trying to reach people who don’t use YouTube though. Thus: these public broadcasts. Always at the same time every week in different local markets across California.

I wonder if that means I’m close to them—close to her. I still don’t know. I’ve tried calling in on that number they list between the sermons. Ask them where Reconciliation is, how I need to find my way. Say that I want to visit as soon as possible.

They always hang up on me.

So I watch for her, whenever I can.

Elena.

My older sister.

She isn’t in the rest of the episode. Not in the background, not in one of Deacon’s devotional messages, not in shots of all the loving homes of good, American Christians, where all the saved children are placed. The one glimpse of her—from that shot in Mrs. Thompson’s classroom.

It’s the only thing I’ve gotten in the last three weeks.

I place the dollar bills next to my empty plate, then leave the diner. It’s too loud. I pass a few booths. Families. Couples. All deep in conversation, all unaware of me. Which is how I like it. It’s easier for me to disappear that way. Easier for me to shove down the bitterness that rises in me during moments like this, when the desire tries to claw its way up my throat.

Because truthfully, I want what they have.

But I don’t get that. Not someone like me.

I’ve taken a lot of rides from strangers this past year. Learned that when you need to get somewhere and you can’t drive and don’t have money, you can’t be too picky.

Also means that sometimes you ride with bad people.

Some of the truckers are creepy. Not all. Not even most. Most are kind. Have seen lots of kids on the road. Don’t know why, but that part surprised me. After I was cast out, I always assumed that there wasn’t anyone else like me. But I’ve met some kids who’ve been rejected. Thrown away. Discarded.

I always think of Cesar, though, whenever I’m getting into a new car with a new stranger.

I met him in Las Cruces at the travel center. First one I ever spent time at after they broke me. He found me scarfing down the remains of a burrito some bougie family tossed in the garbage because their daughter took a bite and didn’t want it anymore. Gave me a bottle of water, a change of clothes. My first belongings.

Then he gave me advice.

Cesar was scrawny. Brown like me. Had a shaved head. Rough around the edges. He wore torn denim jeans and a gnarly leather jacket with punk patches glued to it over a tattered Discharge tank top. It struck me that his clothes looked like they were falling apart not because it was an intentional style, but because he was real. His life was real.

And he knelt before me. Said he could tell I was new. Could smell it on me, see it in the way I devoured food. He told me not to be so open. So desperate. “People like us are desperate,” he explained as I continued eating. “But don’t show it. Don’t let them know.”

I swallowed. Eyed him suspiciously. “Know what?”

“Anything about you. I can see your whole story on your face.”

I looked away. No, he couldn’t. No one could.

“Someone hurt you,” he continued. “Badly. Probably threw you away.”

When I looked back at him, my vision blurred.

“See? I knew I was right. You gotta cut that shit out.”

I rose and walked away from him, but he followed. “I been at this longer than you,” he called out. “And if you’re gonna survive out here, you have to hide it all.”

“Why do you care?” I sneered, rounding on him.

“Because I’m just like you.”

No, you’re not.

“At least, I once was.”

No, you weren’t.

“And no one else is actually going to help you.”

I suddenly had no appetite. Tossed the remains of the burrito in a nearby trash can, very aware of what I had just been eating. Leftovers. A stranger’s leftovers. No one had offered me this.

No one else was going to help.

And so I sat there, on the curb outside a travel center in Las Cruces, New Mexico, and Cesar told me his rules. They worked for him. Work for me, too.

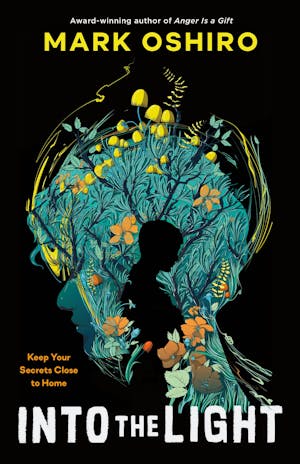

Copyright © 2023 by Mark Oshiro