• 1 •The Lie of Whiteness

The Gringo, locked into the fiction of white superiority, seized complete political power, stripping Indians and Mexicans of their land while their feet were still rooted on it. Con el destierro y el exilio fuimos desuñados, destroncados, destripados—we were jerked out by the roots, truncated, disemboweled, dispossessed, and separated from our identity and our history.

—Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera

The Baggage That Immigrates with Us

For the first eleven years of my life, the pieces of my cultural identity were not spread across borders. I was a Mexican in Mexico. If I ever felt like I didn’t belong at school, it was not because I was ethnically different. The culture was mine. I was Mexican with no quote marks. I didn’t need to eat spicy food to prove it. Taco trucks weren’t a fad, and I didn’t need English-language documentaries to explain what makes a taco a taco de guisado. Eating the food, speaking the language, dancing to the music—it was all like breathing air.

Still, I began to learn the importance of whiteness as a child in Mexico. I was told by my lighter-skinned grandma not to spend too much time in the sun or I would get even more prieta. The only time I was allowed to wear my hair parted down the middle was on El Día de la Virgen de Guadalupe, the one day out of the year when I should look Indigenous on purpose. If my words had grammatical mistakes, my tías would say, “Te pareces a una Chalitla,” even though I probably am a Chalitla, like the other Indigenous people in our region of Guerrero. My grandmother heard those same sentiments from her grandmother. In an effort to spare children from the same contemptuous mockery, we tell them to marry someone who is lighter skinned so they can help “improve the race.” The casta system set up by the Spanish during colonial times to socially rank people based on their proximity to Spanish blood, with those who were white and born in Spain at the top of the hierarchy, has been officially dead for centuries, but we keep perpetuating it by repeating the message that lighter skin is more valuable to the next generation. When I was a little girl, I wasn’t able to discern these racist displays by my family, but I did internalize them.

Whiteness is celebrated in every area of Mexican life, so I aspired to hold the beauty of white Mexicans on my face, on my skin, and in the roots of my hair. The problem wasn’t just at home. The media we consumed also shaped how my family and I viewed ourselves and those around us. I saw white Mexicans on TV, in magazine ads, on billboards. White Mexicans sang my favorite songs from Luis Miguel’s “Cuando Calienta el Sol” to Paulina Rubio’s “Mío.” Thalía starred in my favorite telenovela, Marimar. If darker-skinned Mexicans appeared in telenovelas, they were portrayed as the help or the evil mistress, or they were caricatures of Indigenous or Black Mexican culture. It wasn’t until July 2020 that the first Indigenous Mexican model, Karen Vega, who is Oaxacan, graced the pages of Vogue México.

In 2019, when Yalitza Aparicio was nominated for an Oscar for Best Actress for her lead role as Cleo in the film Roma, Mexican racism tore through the thin linen shade where it pretends to hide. Famous telenovela star Sergio Goyri was caught in a viral video, calling Aparicio “una pinche india,” who didn’t deserve her nomination. The only one who did, according to Goyri, was Alfonso Cuarón, the film’s white Mexican director. Further, to help make Yalitza more palatable to a Mexican audience, magazines like ¡HOLA! photoshopped her to look lighter, skinnier, and less Indigenous. Many Mexicans deny the possibility of any of us being racist because, as Goyri said when confronted by the press, “a proud Mexican cannot be racist.” But so many of us are still covered in the ashes of colonization.

When I was about eight, I was playing in El Zócalo with some friends from school when an Indigenous girl approached us to sell candy. One of the light-skinned girls started taunting her, saying she smelled like caca. Another girl said, “Qué fea prieta, déjanos en paz.” I looked very much like that Indigenous girl, except I was wearing a Catholic school uniform. I joined in on the ridicule, telling the Indigenous girl, “Ni siquiera hablas bien español!” I hoped that in my insults the other girls didn’t recognize the indigena in me. I resemble mi abuelita Enedina, my dad’s mom, who was Indigenous. But we didn’t talk about that at home. Instead, my mom would tell us how mi abuelo Pedro, who died when my dad was seven or eight years old, looked like a Spaniard. She would say, “Qué bueno que tu papá no se parece tanto a su mamá,” Except he did. My dad had beautiful dark skin, and thick hair and full eyebrows. When I was a newborn, my mom buzzed my entire head to get rid of my curls, because they reminded her of my abuelita’s.

I sometimes think about the girl in El Zócalo and ask her for forgiveness.

One of the hypocrisies in Mexico is that we learn to be proud of the mighty Aztecs who built the pyramids, but not of the Indigenous person who has survived all these centuries, who speaks Nahuatl or one of the other sixty-eight Indigenous languages still spoken in Mexico.1 Mexican pesos are decorated with the Aztec calendar. We take school trips to Teotihuacán, to experience the glory of our Indigenous past, but we don’t pay any attention to the present-day Indigenous communities in desperate need of resources. We can take pride in the heritage left to us by our Indigenous ancestors and at the same time reject that we are in fact still Indigenous, too.

The song of our colonizers plays the moment we are born despite more than two hundred years of Mexican independence. If you spend enough time around your Mexican family, you’ve undoubtedly heard someone brag about their “abuelito de ojos azules.” We want so badly to be white that some of us will claim our mother’s grandpa was from Spain, even if he wasn’t. Even if by doing so, we are belittling ourselves.

For Black Mexicans, the erasure and racism are even more prevalent. Mexico has hidden an important part of our history. After the Spanish were done killing Indigenous peoples and still needed to enslave people for profit, they brought Africans to the American continent, whom they viewed as “strong for work, the opposite of natives.”2 As Ibram X. Kendi points out in How to Be an Antiracist, Indigenous people were viewed as weak, and that justified our genocide just as the perceived physical strength of Black people justified their enslavement. A few Africans also arrived as free men and were conquistadores.

Black Mexicans have been part of our story for centuries. Yet they have had to fight to be recognized as Mexican. The year 2020 marked the first time the country counted Afro-Mexicans as part of the official census. In 2015, Mexico’s statistic institute estimated the Black Mexican population to be around 1.3 million3, yet their history remains obscured and whitewashed.

My nephew, a junior in high school in Mexico, was visiting me in Los Angeles a couple of years ago when I asked him if he knew that Vicente Guerrero, the second president of Mexico, was Black. “Are you serious?” he said. “In all the pictures he looks ‘bien blanquito.’” Because of his stature, he could not be ignored or erased from history, but his standing didn’t stop him from being whitewashed. Even when negating the history and importance of Indigenous and Black people simply can’t be done, we are not allowed to claim power alongside our Indigenous or Black identities—the identity must then be erased. This strategy is deployed from Mexico to the Dominican Republic to Europe.

Vicente Guerrero was the son of a Black father and an Indigenous mother. Inspired by the Haitian Revolution, Guerrero fought to end African slavery in Mexico some thirty years before it was abolished in the United States. Schools all over Mexico bear his name. It’s tragic to think that our people in Mexico died to gain independence, freedom, and equality for the Indigenous worker and for the enslaved African, but many haven’t been able to shake the colonizer in our heads. A document of twenty-three principles for the future of a free Mexico, called the Sentimientos de la Nación written by José María Morelos Pérez y Pavón in 1813, included the prohibition of slavery “forever,” as well as the abandoning of the caste system, and only “vice and virtue” making people different from one another. When John Quincy Adams was secretary of state, he wrote a letter to his brother in 1818 in which he described America’s independence as “a War of freemen, for political Independence,” and Mexico’s as “a War of Slaves against their masters.” Adams was right that Mexico’s independence—as well as the independence of other Latin American and Caribbean countries—was different. The independence of the United States was one where elites sought liberty only for themselves and for the protection of their land and property, which included African people. Mexicans won our independence from Spain to free the most oppressed, even if it hasn’t played out that way.

We’ve been so beaten down by white supremacy that we have yet to be truly free. Whiteness infiltrates Mexican institutions and life just as it does those of its neighbor to the north. It is a problem that plagues much of Latin America. In Bolivia, for example, the first and only Indigenous president came to power in 2006, 181 years after the county’s independence. Colombians have taken to the streets to protest racist police, because Black people are killed more often there, too. From Brazil to Mexico, Indigenous and Black people remain oppressed.

When I go back to Mexico now, I am deeply saddened to hear the same everyday racist talk I heard when I was as a kid. I often wonder if I had stayed in Mexico, would I see clearly how we’ve been tricked to yearn for whiteness so that we don’t strive for justice?

I often think of a brilliant line by author Domingo Martinez when I grapple with our own people becoming the oppressor when they’ve known the scourge of whiteness: “There is nothing more potentially hostile than the indigenous ego interpreting the laws of his conqueror upon his own people.” We become vicious to our own bodies, to our own souls. In our own home countries we learn to view white as superior, as something we should aspire to. Then when we immigrate to the United States, we bring those sentiments packed in our suitcases. Those ideas are hardened on our hearts like a wax seal the minute we cross into the United States.

Mexico introduced me to the lies of whiteness, but it was the United States that taught me just how corrosive white supremacy truly is. Seeking whiteness is a matter of survival here: white skin in the United States means you exist. It means you matter. Some of us flatter ourselves white by virtue of our education, our job, or our bank account—despite the nopal on our faces, we introduce ourselves as “Spanish” at work. In the United States, whiteness didn’t just render me less than—it rendered me invisible. Here a Brown Mexican seems to have no past, no future, and no identity. I was further ostracized because I was undocumented. It was the ultimate layer of being alien. But here, in my new home, is also where I learned to fight it.

When White Became White

A few years ago, I was at a birthday party, talking with a friend, when a white woman introduced herself. As is natural in this kind of setting, she proceeded to ask us how we knew the birthday girl. “We went to college together,” I responded.

She then asked where we were from, to which my friend Kevin replied, “I’m from Brownsville.” Not satisfied with his response, she asked where his parents were from. Once more he said, “Brownsville.” This is a scene I’ve watched before. I squeezed the drink in my hand so hard I thought I might break the glass. She continued her interrogation with a question every Latino has heard: “But, I mean, where are you from from?” The answer was once again Brownsville. She snapped and hissed, frustrated that Kevin wasn’t giving her the response she was fishing for. To her, and to many people, all Latinos are immigrants, presumed to have arrived with wet backs across the Rio Grande.

I jumped in and asked her where she was from. She said she was from Jersey, her parents were from Jersey, and before Jersey, “Well, I am just white. My ancestors are all American.”

American equals white equals American. Were her ancestors Italian, Irish, German, Dutch, Ukrainian? Historically, not all Europeans were welcomed with open arms, but how quickly white Americans take refuge in their whiteness. Immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe were not considered white enough when they first immigrated across the Atlantic. Their arrival felt like a corruption of American life and a downgrade in the genetic makeup of the country—they were viewed as illiterate and too docile.4

A white person today can simply say, “I am white; therefore I am American,” but a Mexican with centuries of history in this land must explain where we are really from.

How is it that European immigrants become unquestionably American? How did white skin became the determining factor for claiming Americanness? It was not a matter of language acquisition, or success, or patriotism, as some claim. Germans, who in the nineteenth century constituted the largest non-English-speaking immigrant population in the United States, continued to speak their native language exclusively, and often their U.S.-born children didn’t speak English, either. Even fifty years after arriving in the United States, many of them spoke only German.5 European immigrants were not smarter or more hardworking. They did not become American by virtue of their success. The tenements in the Lower East Side of New York City demonstrate that European immigrants came largely from the working class, impoverished people scrapping by to survive. Still, by the twentieth century, Greek, German, French, and other European immigrants sat comfortably under the umbrella of whiteness, as decisively American.

Instead, becoming white has long meant standing on someone else’s neck. It’s also been about bargaining away your culture and vying for a better position in humanity’s made-up hierarchy. The poet Diane di Prima speaks to how this was true for early European immigrants: “[Whiteness] was not something that just fell on us out of the blue, but something that many Italian Americans grabbed at with both hands … they thought, as my parents probably did, that they could keep these good Italian things in private and become ‘white’ in public.”6 In other words, becoming white meant trading in Italian culture, language, food. It meant assimilating. In How the Irish Became White, Noel Ignatiev explains that the Irish not only had to leave their roots behind but had to define themselves as different and above Black people. Back in Ireland, many were against slavery, but upon arriving on the shores of the United States, they were willing to part with their beliefs if it meant holding on to the privileges of whiteness in America. They opposed emancipation, fearing that Black people, no longer enslaved, would flood the labor market and they’d be left on the street. How American to place the value of a job above that of Black lives. Frederick Douglass liked to point out that his old job at the plantation remained open should any white man like to apply.7

As white immigrants were brought into the fold, my people were further excluded. The whiter others became, the more non-American we became. The Mexican-American War, in which the United States illegally invaded Mexico, served to solidify the notion of Europeans as patriotic Americans and Mexicans as trespassers. Nearly half of the U.S. soldiers in the war were foreign-born, but they became lauded as patriots. “The Killers,” as the most savage battalion was called, were hailed as heroes for their display of the “extremest of bravery.” By executing Mexicans, European immigrants earned their Americanness—their whiteness. They were too willing to accept that Mexicans were like dogs with no breed, a lesser race, and they were therefore justified in taking Mexican land, in killing us.*

Many historians have studied the complexities of how European immigrants became American, but it’s hard to ignore what they all had in common that other groups of immigrants did not—their white skin. European immigrants assimilated and gained power because whiteness was available to them. That’s what made them American. That’s what made grandiose myths. This country many times uses them as a shiny example of what immigrants should be, as a backdrop of everything we are not. But white became white by excluding others.

Today, there is no hope of becoming American in the way America demands—the white way—for those who come from a “shithole” country, as Trump famously labeled places like Haiti, El Salvador, Nigeria, and other countries in Africa. “[N]ow that our immigrants are overwhelmingly poor Brown people, the rules of political correctness require that we submit to their culture,” writes Ann Coulter, an extremist who has played a major role in crafting the national conversation about immigrants in conservative circles. She maintains without irony, “we no longer ask anything of immigrants in terms of assimilation. We can’t. That would be ‘racist.’”8 But the opposite is true. We demand assimilation, knowing that no amount of it can offer belonging because our brown skin can never be made white.

In the Name of Patriotism Whiteness

One summer day I visited a friend in a suburb of Dallas, Texas, and I got lost in the winding dead-end streets. It was bright daylight, but I was scared. I was an undocumented Mexican, driving without a license, since Texas denies them to undocumented people. Every single house, replicas of one another, had a U.S. flag hanging from their white porch. I still hope one day the American flag will be a welcoming sign of unity that I can fly from my home without inadvertently sending a message that people like me don’t belong. But these symbols today feel like a scar from a toxic relationship I took too long to leave. The battle wounds of assimilation still sting in my body. The wind that day was hardly blowing, and instead of dancing on the breeze, the red and white stripes sagged, looking sad, as if bogged down by all the racist ideas embodied in it. By all the horrors Americans have committed in the name of freedom, for the sake of patriotism.

More than a decade later, a twenty-one-year-old white man walked out of a house just like the ones on that street and drove for ten hours, from Allen, Texas, just outside of Dallas, to El Paso, as he later confessed. I wonder if he saluted a U.S. flag before he walked into the Texas heat. He must have chosen El Paso with its large Mexican American population on which to inflict the most pain. He must have chosen a Walmart on a week when back-to-school shopping was at its highest to protect his country from Mexicans, from people who look like me, as though America was not also ours.

On August 3, 2019, he took his AK-47 and targeted and killed twenty-three mostly Latino men, women, and children. His goal was to kill “as many Mexicans as possible” and to stop the “Hispanic invasion of Texas,” he wrote prior to the shooting in a manifesto authorities believe he authored.9 He didn’t just mean people of Mexican heritage or undocumented Mexican immigrants, but Brown people who he understood as Latino (given police officials say he fired indiscriminately). He didn’t stop to ask any of the twenty-three people he killed for their papers, or if they came to the United States “the right way” or immigrated “legally.” That’s because it wasn’t about legality. It wasn’t about assimilation. It was a racist act. It was about our brown skin in America. It’s always been about that.

It was only a matter of time before dangerous words became dangerous actions. Peter Brimelow, an extremist who, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center, “warns against the polluting of America by non-whites, Catholics, and Spanish-speaking immigrants,” writes in Alien Nation: “The American nation has always had a specific ethnic core. And that core has been white.”10 If by white he means exclusionary and racist, then I agree. Alien Nation was published in 1995, but the narrative of Latinos as outside the American core, as foreigners, as threats, has been at the center of American history, past and present. America has denied that our people have always been part of this land. “We are a nation besieged by peoples ‘of color’ trying to immigrate to our shores,” writes another right-wing extremist, David Horowitz. As long as Latinos continue to be viewed as invaders, we are in danger.

In September 2019, Trump asked during a rally in New Mexico, “Who do you like more—the country or the Hispanics?” The framing of this question separates Latinos from America. It ignores the fact that in the United States, Americans and Latinos are one and the same. There are more than 60 million of us, and 80 percent of Latinos under thirty-five are American-born.11 In Texas, 70 percent of Latinos were born right here in the USA. The Guardian found Donald Trump used the word invasion when referring to the southern border and the need to build a wall in more than 2,000 Facebook ads in a nine-month period.12 USA Today, in a study of five dozen rallies and events, found that Trump used words like invasion, criminal, predator, killer, animal, and alien more than five hundred times when speaking of immigrants.13 Nativists have used the idea of Latinos “taking over” as a means to get rid of us, discreetly through racist policies and violently with AK-47s.

It is not just members of right-wing fringe groups that espouse the view that Latinos are foreigners. In Politico Magazine, Adrian Carrasquillo reported on the hurt, fear, and pain Latinos experienced in the aftermath of the 2019 shooting, even in the “liberal” city of Los Angeles. He wrote a story of his friend’s husband who “overheard white men at the community pool remarking that while they didn’t agree with the killings … they, too, didn’t want white people to be ‘wiped out’ and for Hispanics to ‘take over.’”14 How novel of them to stand against the murder of Latinos. This rhetoric perpetuates the idea of Latinos as foreigners no matter their immigration status. That we are American didn’t matter to the shooter in El Paso or to the very people who we’ve hired to represent us. Texas Senator John Cornyn dismissed the terrorist act as a “very complex problem,” to which “sadly … like homelessness … we simply don’t have all the answers.”

This reluctance to call the massacre what it was—a terrorist act carried out by a white supremacist against Latinos—is just as damaging as loading a gun. Not everyone needs an AK-47 to hunt Brown bodies to be complicit in our deaths. But these white men will continue to wear a U.S. flag pin on their fancy suit jackets and demand that we love their country, the same country that has tried time and time again to “send us back to where we came from.” They will hide their rotten souls behind patriotism, with flags flying from their porches.

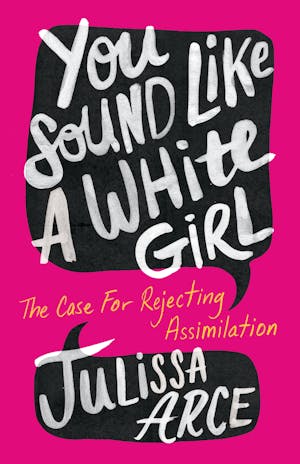

Copyright © 2022 by Julissa Natzely Arce Raya. All rights reserved. For information, address Flatiron Books, 120 Broadway, New York, NY 10271.