CHAPTER 1

1883

When my father found my grandmother dead, he let out such a cry that later our neighbor claimed to have heard it, even though his home was a full length of field from ours. I might have been convinced he was lying if I hadn’t heard my father’s wailing with my own ears. The sound of a man’s heart shattering into a million pieces was like the cry of a wounded animal—fear and suffering all mingled together. A chorus of pain rising to the heavens.

I went to see what had happened and it was then that I saw her—my grandmother, my father’s mother, her brown skin ashen and clinging to her bones like wet paper, her knotted hands balled into fists at her sides. The skin of her lips had curled back, exposing her teeth. Horrifying as those things were, they weren’t even the worst part. The worst of it was the look in her eyes. They were wide open, staring up into nothingness. I don’t claim to know much about the properties of one’s soul, but whatever life had lived in her had fled, and all that was left was an empty shell.

I was told the corpses I would eventually see as part of my medical studies would not be wide-eyed with gaping mouths. They would be people who had donated their bodies to the London School for Medical Studies, and their mouths and eyes would be sewn shut. My stomach lurched at the thought.

My father was the only reason I was pursuing medicine at all. He would see me become a doctor, though I might have been content to study law. My father didn’t care about being content, but not because he didn’t love me or because he didn’t want me to be happy. He simply chose to take the path of least resistance.

He focused on respectability and impressed upon me the importance of how I must be perceived by the people around me. Those were things I could control if I made the “right” choices, though it never made much sense. I couldn’t control how others viewed me, especially when they seemed hell-bent on ascribing to me any number of unfair or untrue attributes. My discontent was a weakness in my father’s eyes. He had no answers for me when I asked him why, if becoming a doctor would grant me respect, nearly every single one of the handful of Black graduates of the London School for Medical Studies couldn’t find a permanent position at any of the city’s hospitals unless they were orderlies, body haulers, or groundskeepers. He knew as well as I did that I would have what I was allowed, and nothing more.

My mother was meant to accompany me to the city, but my father convinced her that I could manage the journey on my own. She and I both understood it was because he couldn’t afford the extra train fare. I did everything I could to let her know that I would be all right without her, though I didn’t really believe that at all.

The train lurched through the London streets under carob-colored clouds. Smoke in shades of charcoal billowed from chimneys, blotting out the sun, and people pressed in on each other as they crowded the streets. London had a great many faces, some of which were unknown or, at the very least, unseen by the average Londoner. To be poor was to be frowned upon, stepped on. To be poor and Black was akin to being invisible.

A pang of anger knotted in my gut. What I would give to not see those terrible, twisted faces looking past me as they trampled me underfoot.

* * *

I disembarked and made my way through London’s bustling streets to the Laurie boardinghouse. My father had made arrangements for me to stay there during my studies, and as I came upon it in the early evening, after slogging through endless rivers of waste in the drizzling rain, it looked like something that should not exist. That it was still standing was a miracle considering the angle of the walls and the pitch of the roof. It was leaning on the building next to it, which was only slightly less dilapidated.

I knocked on the door and waited as heavy footsteps approached from the inside. A small viewing window slid open, and a pair of brown eyes stared out at me.

“What do you want?” the woman asked, her voice thick with suspicion.

“My name is Gabriel Utterson. My father—”

The woman slid the little opening shut before I could finish my sentence.

I stood there in the rain, clutching my bag and wondering if I’d somehow ended up at the wrong address.

The lock clicked and the door yawned open. The woman on the other side was small and round with a heavy brow. She must have used a footstool to peer out because she was a full head shorter than me.

“You going to stand in the rain? Or you going to come in?”

I quickly stepped inside and she slammed the door, locking it behind me.

“Leave it open long enough and someone is liable to run in here.” She narrowed her eyes at me. “Your father told me all about you. Said you’re a bit of a bleeding heart, and so I feel compelled to remind you that you are not in the countryside anymore, Mr. Utterson.”

“No, ma’am, I’m not.”

She nudged me into the narrow front room with a ceiling so low I could have reached it with my outstretched hand. It was warmed by a fire, its flames lapping at the damp bricks surrounding the hearth. There were chairs and wooden rockers all around and everything smelled of cooked meat and cigar smoke.

“Welcome to Laurie’s,” the woman croaked. “I’m Miss Laurie. This is my place. My rules. Got it?”

I nodded. “Yes, ma’am.”

“You’re on the second floor. Room seven. No company, no loud noises. You’ll be out by noon on the last day you’re paid up for and not a second later, or I’ll have my brother toss you out. Meals are at eight, eleven, and seven. You’re not here, you don’t eat. Stay out my kitchen.”

“Yes, ma’am.” All I wanted to do was change my clothes and go to sleep. Only when she’d gone over the location of the outhouse and washroom, the laundry schedule, and the coal ration did she dismiss me and take up a seat directly in front of the blazing fireplace.

I dragged myself upstairs and found my room at the end of the hall. It was the size of a closet with a small fireplace and a sleeping mat stuffed haphazardly with hay, but the floor was freshly swept, and there was an oil lamp and set of clean folded linens waiting for me. The night was black outside the single window in the outer wall. I didn’t even bother changing my damp clothes before I fell exhausted onto the mat.

I lay there for a moment, waiting for sleep to find me, when I heard footsteps in the hall. I waited in silence as my eyes adjusted to the dark.

The steps moved to my door.

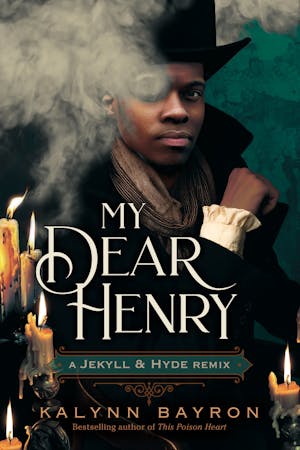

Copyright © 2023 by Kalynn Bayron