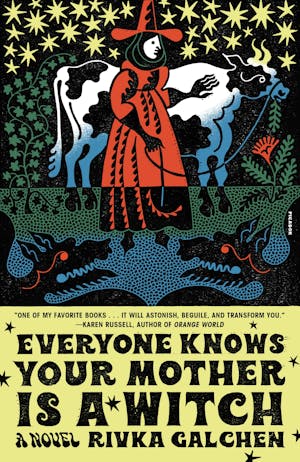

Herein I begin my account, with the help of my neighbor Simon Satler, since I am unable to read or write. I maintain that I am not a witch, never have been a witch, am a relative to no witches. But from very early in life, I had enemies.

When I was a child, our cow Mare at my father’s inn was cross and bitter toward me. I didn’t know why. I wouldn’t hesitate to put a blue silk ribbon on her neck if she were here today. She died from the milk fever, which was no doing of mine, though as a young child I felt it was my doing, because Mare had kicked me and I had then called her fat-kidneyed. Was she my enemy? It takes time and experience to gain a cow’s trust.

Now I’m seventy-some years old. I’ll spend no more time on the enemies, or loves, of my youth and middle age. I’ll say only that I’ve never before had even the smallest run-in with the law. Not for fighting, not for cursing, not for licentiousness, not for the pettiest theft. Yet attributed to me in this trial is the power to poison, to make lame, to pass through locked doors, to be the death of sheep, goats, cows, infants, and grapevines, even to cure—at will.

I can’t even win at backgammon, as you know.

* * *

IF MY DEFENSE fails, a confession will be sought through torture, first with thumbscrews, then with leg braces, then with the rack—or something like that. It depends who the council hires for the job. If mercy is taken upon me, I’ll be beheaded and then burned. If no mercy is taken, I’ll be burned without first being beheaded. That happened to seven women last year in Regensburg. My children, with some help, have been coordinating my defense.

There are two things a woman must do alone: she does her own believing and her own dying. So says Martin Luther. Or so you say that Martin Luther says, or said. I was born the year Luther died. I took Catholic Communion only one time, in error. My daughter Greta is married to a pastor who says that’s okay. My son Hans agrees. I hold Luther in highest esteem. He, too, was vilified. Again, I’m grateful to you, Simon, for sitting with me, for writing for me, for being my legal guardian.

This is my truest testimony.

On a Tuesday midmorning in May of 1615, four long years ago now, there was a gentle knock at my door. A freckle-faced young boy, with eyes downcast, said I was to follow him to see the ducal governor Lukas Einhorn. The boy had light eyes and wore clean, short trousers. It was hot out. I offered him a cool, weak wine, but he blushed and refused. Why was I being called? I asked him. He said it was an official summons. But he didn’t know for what.

You’ll remember, Simon, that it was a rotten spring that year. The beets were wrinkled, the radishes spare. The rhubarb, usually a celebration, was like straw, and same for the asparagus. The preceding winter had been fierce. One snowy eve a goat had turned up at my door, a beggar like Christ, I thought, and so I let the goat in, and he was so frozen that when he knocked his head against the leg of my table, his chin hairs broke off like sugar plate. I met a shepherd from outside Rutesheim whose nose fell off when he wiped it. The months had been ominous. The price of a sack of flour had nearly doubled. Half the town was having to borrow from the grain stores.

But it was a sunny day that Tuesday. I put on my boots, kissed my dear cow Chamomile, left behind my washing.

And I had a smug guess as to why I was being summoned. You’ll laugh at me when I tell you this. I thought that Lukas Einhorn wanted my help. Mine! On account of the dark and difficult seasons, you see? He was a new ducal governor and he had no idea how to manage. I suspected that Einhorn wanted me to ask my son Hans to prepare a horoscope for him, or even to prepare a whole astrological calendar. I began to be annoyed, assuming Einhorn would expect the work to be done for no pay. So many of the so-called nobles petition Hans for astrological calendars, for weather predictions, for personal horoscopes. Even Emperor Rudolf had asked him: What do the stars say for war with Hungary? And even the Emperor never got around to paying. The new emperor is no better. It’s always the same with some people. They may as well ask him to mend their hose. Hans was already living in Linz then. He had just remarried, and was teaching at a small school. He had been denied a job at his university in Tübingen on account of some nonsense about what Communion wafers are made of, and though Hans is known at all the finest courts, he is paid only in insubstantial status. That May he was caught up in all sorts of conflicts with printers, and also he was trying to find a suitor for his stepdaughter. I was seen as having Hans’s ear. But the man only has the two ears same as God has gifted the rest of us.

I get so little acknowledgment here in Leonberg of Hans’s place in the world, and that’s good—who wants to bring out the devils of envy? But I suppose I was waiting for the chance to dismiss a compliment, to say that Hans’s accomplishments were his own, and not mine, though Hans does say, and I don’t disbelieve him, that the mother’s imagination in pregnancy impresses itself upon the child. And Hans does look like me, not like his father, may he rest in peace or whatnot. As I followed that boy, I thought: Okay, I’ll ask Hans for the horoscope, or whatever this ducal governor wants, it will be good for my son Christoph, who had only that very year purchased his citizenship, who wanted to move up in the world, as Hans had, and why not? We passed one of the small civic gardens where hurtsickle and blue chamomile had been left to overcrowd each other. A white rabbit crossed my path. Outside of the ducal governor’s home, a stone engraving of Einhorn’s shield was being finished by a young mason. The shield showed a unicorn rearing up on its hind legs, like a battle horse. A vanity.

In the cool front room of the ducal governor’s residence, the boy showed me to a seat next to a vulgarly stuffed pheasant and then left. The pheasant had green glass eyes. The feathers looked oily; the pheasant looked evil. Turned to evil, I will say, as opposed to born of evil. I was thirsty. I waited there, next to that unmoving pheasant.

Copyright © 2021 by Rivka Galchen