Book details

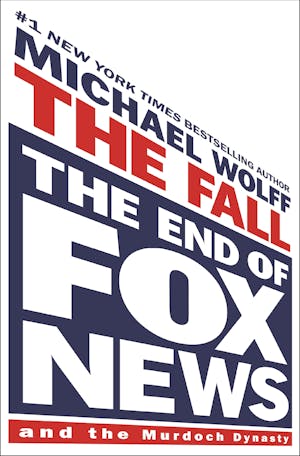

The Fall

The End of Fox News and the Murdoch Dynasty

Author: Michael Wolff

About This Book

Book Details

New York Times Bestseller

“All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”

—Leo Tolstoy, Anna Karenina

“Michael Wolff’s books were my foundation and port of entry for working on Succession.”

—Jeremy Strong (“Kendall Roy”)

Meet the Murdochs and the disastrously dysfunctional family of Fox News. Until recently, they formed the most powerful media and political force in the land, for better or worse. Now their empire is cracking up and crashing down.

For almost three decades, Fox News has not only made political careers (see: President Donald J. Trump) but also fundamentally altered the political landscape of the United States. It is a truism: as Fox goes, so goes the nation—into further divisiveness and awash in fake news, a gleefully polarizing company. But just as Fox has pushed America apart, now it too is coming apart. As is the family dynasty behind it.

In his irresistible trilogy on the chaotic presidency of Donald Trump—Fire and Fury, Siege, and Landslide—the gadfly journalist Michael Wolff led readers deep into the twisted corridors of the White House. Now, drawing on years of unprecedented access to the Murdoch family and key players in the world of Fox, he plunges us behind the scenes of another empire of influence, and the result is astonishing and unforgettable.

Here is Rupert Murdoch, the ninety-two-year-old Australian billionaire—a fading titan, concerned about his legacy but more concerned about profits. Here are his contentious progeny, jockeying to take over when the old man is gone. Here is star anchor Tucker Carlson, hiding out in his island homes, considering a run for the presidency while his bosses have other plans for him. Sean Hannity, the richest man in television, has his own plans: to put the former POTUS back in office, against the bosses’ wishes. Meanwhile, Laura Ingraham is just trying to survive in the last man’s man’s world.

Empires fall. Kingdoms come to an end. As lawsuits pummel the financial bedrock and reputation of the network, anchors scramble, and the battling Murdoch heirs make the Roys of TV’s Succession seem downright Brady Bunch, Michael Wolff documents, in riveting and revelatory real time, the final days of Fox News.

Imprint Publisher

Henry Holt and Co.

ISBN

9781250879271