1

Each day, countless fleets of camel caravans sailed across the desert sea to reach Timbuktu.

Here, in this port city on the southern edge of the Sahara, waves of men, women, and children flooded the market, searching for supplies. Farmers and craftsmen proudly showcased their wares from behind wooden stands or in front of tents. Threads of dancers wove through cheerful crowds; juggling entertainers could be found on every corner. Travelers’ stories of far-off lands rose and fell with the playful chords of musicians. Vibrant colors and savory scents swirled in the air as Timbuktu teemed with the trading, buying, and selling of everything from exotic spices to brilliant fabrics to precious salt and gold.

But today, Timbuktu was still.

I stood in front of a wooden platform, along with what felt like half the market goers. Rain poured from the skies, soaking through my brown wrapper. Thunder rumbled as a Songhai general was dragged onto the platform by soldiers who were not his own.

They forced the general to his knees, the wood beneath him groaning over the incessant patter of rain. His wet robes were stained with blood and grime. Water trickled from his turban, down his bruised face.

A third, smaller man drifted onto the platform. Lines were etched into his face, like ripples in a shadow. Each line marked a history—a birth, a marriage, a death. He frowned as his gaze swept over the crowd, chronicling yet another wrinkle, another event.

He extended his arms on either side of himself, and his billowing sleeves crowded around his elbows. “Ọba kìí pkọrin.”

The customary introduction of griots pierced the air. The griot paused, allowing his baritone words to take their place among the crowd, before continuing in accented Arabic, “Gather, gather, hear me now. The Songhai rule this city no more. As of today, Timbuktu belongs to the Aláàfin of Yorùbáland.”

The griot gestured to a group of soldiers standing nearby. From within their circle, an old man stepped forward. He wore a red and white kente toga that draped over one of his forearms and shoulders. Beneath the painted white dots covering his body, his skin was as brown and gnarled as an ancient baobab tree. It felt as though time itself paused to accommodate his slow approach.

The griot stepped back as the old man mounted the platform; griots represented nobles and the people, but divine correspondence with the òrìṣàs was left to babaláwos.

The babaláwo looked down at the general and raised a fist. Slowly, very slowly, he uncurled his fingers, uncovering a single cowpea in the center of his palm.

People around me recoiled. I leaned forward. I had heard of the sacred Yorùbá bean, but I had never seen one myself.

Although the general had not flinched, his full lips were clamped thin. From where I stood at the front of the crowd, I saw the fear that flashed across his eyes. He struggled in vain as soldiers pried open his jaw, and the babaláwo forced him to eat the cowpea.

“Great Ṣàngó,” the babaláwo cried. His gossamer voice whirled around me, as though entwined in the wind. “This is the man who led your enemies. What is to be his fate?”

There was no answer, of course; the òrìṣàs never personally descended from the heavens to speak to the humans they presided over. Wind howled around us, growing crueler in its acceleration. Fruits were blown off nearby stands; orange sand surged forth. As I shielded my face from the storm, I wondered if all of Timbuktu would be uprooted before the trial ended.

Then lightning ruptured the sky, and the world shuddered under the thunder that followed.

“Ṣàngó has spoken,” the griot boomed. He beckoned a soldier forward.

Rage rippled through the fear on the general’s face. “This is what you call justice? You Yorùbá are nothing but a tribe of superstitious pagans—”

A soldier plunged a spear into the side of the general’s neck. His declaration sputtered into wet gurgling as blood poured from the wound. He fell onto the platform, seizing, until his movements gradually came to a stop.

The babaláwo raised his arms to the sky. “Ṣàngó yọ mí.”

“Ṣàngó yọ mí,” the crowd echoed. Ṣàngó saved me.

The affirmation scratched my throat, threatening to bring more than words with it. But like the rest of the onlookers, I knew to thank the god of thunder and lightning for not condemning me to death instead. His wrath was as deadly as wildfire and just as easily spread.

The griot said, “Nothing about your life in Timbuktu need change. So long as your governor pays tribute to the Aláàfin, he may continue to rule as he sees fit.” He turned to a richly-dressed man standing beside the platform in between two soldiers. “Do you accept these terms, or are you determined to follow the fate of Timbuktu’s former general?”

The brown seemed to drain from the governor’s face. He fell to his knees, his hands clasped in front of him. “I am honored to serve the Aláàfin,” he said. Then, in stunted Yorùbá, he added, “An honor.”

The griot nodded, and the crowd began to disperse, many of them taking cover from the rain. But I remained rooted in place. I watched as soldiers stepped forward to retrieve the body of the Songhai general. They hauled it onto a wagon like it was a sack of garri, moving with an efficiency that suggested they had done this for years, though they could not have been much older than I was, around the age of nineteen.

“There, there.” A robust man slid next to me. He laid a meaty arm around my shoulder, his palm moist against my skin. “I understand your shock. Is it difficult to wrap around your head?”

“I’ve seen executions before,” I said quietly. Though this was true, I had never seen lightning be the final verdict.

“I don’t mean the execution.” The kindness enveloping the man’s words peeled back to reveal impatience beneath. I looked at him and saw that he was pointing at my head. “Your headscarf is the brown of an overripe plantain,” he said. “It is old and stiff. Difficult to wear, yes?”

From somewhere within the sleeves of his tunic, he extracted a silk scarf so white that it stung my eyes. “My dear girl,” he continued, “your scarf does justice to neither your black nor your beauty. What you need is a bright scarf, for the night sky needs its stars.”

It was then I remembered that I did not know this man.

I shrugged his arm off, and as I made my way through the marketplace, other vendors called out to me, also telling me what I needed.

“Come and see your new sandals,” called a man with a large beard and a larger belly. “The leather is soft and smooth, but they are strong.”

“Fruit directly from the riverbanks of the Niger,” proclaimed a woman as orange as the mangoes she held. “The juice can cure the most stubborn of illnesses.”

The marketplace’s rhythm resumed as though it had never paused. The Yorùbá seizure came as a surprise to no one; Timbuktu sat on agriculturally rich land in a commercially active area. When the Songhai captured the city three years ago, in 1468, they had only been one more addendum to Timbuktu’s long history of changing hands. The city’s population was not made up of just one people; there were the Songhai and the Yorùbá, but there were also the Fulani, the Moors, the Portuguese, and more. The only thing that unified Timbuktu’s inhabitants was a drive for profit. So long as the marketplace continued running, who ruled the city was of little importance.

I had come to the marketplace today with my mother, but in the commotion of the execution, I lost her. Knowing that she would not want me wandering around alone, I decided to head home.

As I rounded a corner onto another busy song-laced street, the Songhai general’s execution replayed in my mind. It was an unconventional method of justice, feeding a cowpea to a man then killing him if lightning subsequently flashed or sparing him if it did not. Perhaps the Songhai general was right to call the Yorùbá superstitious, to imply that the will of their god was nothing more than nature’s chance. And yet—with it being the very end of wet season, today’s rainfall should not have been as heavy as it had been. I could not help but wonder if there was some truth to the common saying that the Yorùbá brought the storm wherever they went.

The rain had dwindled into a drizzle by the time I reached a quieter end of Timbuktu, on the outskirts of the market. The sandy road, less trodden upon here, branched out into evenly spaced compounds. Each were enclosed within waist-high mud-brick walls.

Eventually, I entered the compound of a sun-dried mud house with a flat roof. Its sandy yard was occupied by a handful of women, all of whom wore plain, brown wrappers and headscarves that blended into their skin. Under great plumes of smoke, the women moved between anvils, forges, and furnaces.

Metronomic pings rang through the air as two-handed hammers molded iron and steel into weapons or shaped gold and silver into elaborate designs. One woman sat on a low stool, pounding boiled yam in a wooden mortar for tonight’s dinner. I knelt before them all, my knees sinking into warm mud.

“Good afternoon, aunties,” I greeted.

“Welcome, child,” my aunties chorused without looking up from their work, cuing me to stand.

These women were not really my aunties, but I had called them that for so long that their names had become foreign to my memory. Really, I was unsure if I had ever learned their names—and given that they had called me “child” my whole life, perhaps they never learned mine either.

I made my way to the house. I had just reached the archway when an auntie emerged from inside.

“Why are you going inside?” she asked me. “Is the work at your forge done?”

It was a clear reprimand, for we both knew that the work at our forges was never done. “My mother wants me to take inventory,” I said. It was a task I had been given earlier that day.

Her brow unfurrowed; like all the other women here, she might have never fully warmed up to me, but she had nothing but respect for my mother.

She sighed. “You’ll have to do inventory another time. I don’t want you to wake her.”

She gestured over her shoulder to inside the house. Within the dark single room, one of my older aunties lay on a sleeping mat. Although her eyes were closed, beads of sweat ran down her face, and her expression was pulled taut as though sleep was an arduous task. Alarmed, I noted that she was even skinnier than the last time I had seen her.

“She hasn’t gotten better?” I asked.

My auntie shook her head sadly. “It is the governor’s responsibility to provide for our guild, but even so, he’s as stingy with medicine as with the food he gives us. I don’t think he wants to waste any resources on an old blacksmith.”

I frowned; the woman was not that old. Her sickness might have aged her, but I remembered the unlined, lively face she had worn when she had still been healthy. I had always believed her to be around the same age as my mother.

I shivered, a motion that had nothing to do with my soaked clothes. My mother and I had been blacksmiths my entire life. As unmarried women, it was one of the few ways we could make a living—but sometimes I feared it was what would also kill us. My sick auntie was not the first of us to expire at her forge. Was this to be the fate of my mother and I as well, meeting death exhausted, neglected, and, worst of all, much too soon?

My distress must have shown on my face because my auntie placed a hand on my shoulder. “It’ll be okay,” she said gently. “She’ll wake up soon, and when she does, we should give her something nice. Why don’t you take a short break to make her one of your flowers?”

* * *

Holding silver and tweezers, I sat in my usual spot behind the house, my legs tucked to one side of me.

The silver had been shaped into a cylinder. One of the cylinder’s ends was open, while the other was fused to a star-shaped sheet of metal. It was meant to be a nearly completed daffodil—or, at least, what I could remember of a daffodil’s appearance. I had only seen a real one once, when a trader gifted me the flower.

That day, the trader had arrived in Timbuktu after weeks of traveling with his colorful caravan of slaves, bodyguards, scholars, poets, and fellow traders. Like so many others, the trader had heard of my mother’s and aunties’ abilities, and he had come to request an iron dagger. My aunties always focused on the orders from generals and kings, leaving less important clientele like him to me. My hands had been less steady than they were now, and my eyes less attuned to identify flaws, yet the trader had marveled at my average dagger.

“My dear,” he said in awe, “what is your name?”

Since he already knew my state-given name, I told him my personal name. His eyes widened. “Wait here—I have just the thing for you.”

I thought he was one of those people who tried to skip out on payment, and I thought he was doing a poor job of it—as we spoke, his traveling companions had been paying my mother.

He proved me wrong, however, by returning. “A flower for the child whose name means flower,” he proclaimed, handing me a flower that was a yellow unlike any gold I had ever seen. “This is a daffodil. They grow in distant lands far, far above the Sahara.”

“It’s beautiful,” I said. Then I grew sad, remembering the flowers I always saw in the market. They bloomed in the day, but after the sun had set and the customers had gone, merchants disposed of wilted petals. “But it’ll die.”

“Daffodils do not fear dying, for they have conquered Death himself.”

“Oh.” A pause. Then, “Perhaps you should keep this…”

I tried to return the flower to the possibly delirious man, but he only laughed. “Do not be afraid of daffodils, my dear,” he said, mistaking my wariness of him for fear of the flower. “They used neither strength nor sorcery to best Death. Just a simple song.” He grinned. “From the look on your face, I am guessing you are wondering what that song is?”

I had actually been wondering how a flower could possibly sing. However, the trader was clearly motivated more by his own pride than by my curiosity. So, I simply said, “Okay.”

He sang. He could not hold a tune, and he sped up in odd places only to slow much too abruptly. The beginning of the trader’s song had since eluded me, and I was no longer certain about its ending. However, what I could remember of the song had burrowed deep into my mind.

The daffodil had succumbed to the desert heat two days later. Since then, I had rebirthed it countless times, using whatever metals my aunties spared me from their work. And with each flower I crafted, I sang the little of the trader’s song that I knew, just as I did now.

“You listen to her tale

One her teacher always told

Of roads his son walked

Roads paved with petals of gold

See them bloom, see them shine

See this garden become a sky

With a thousand tiny suns

It’s no lie, it’s no lie

Light the world through the night

Keep this glow inside your heart

Flowers wilt, lands dwindle

But survival is in the art.”

“Beautiful.”

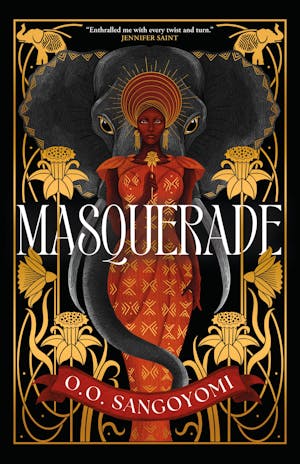

Copyright © 2024 by O.O. Sangoyomi