chapter I

Black Shiny FBI Shoes

THAT'S GOOD THINKING THERE, COOL BREEZE. COOL BREEZE is a kid with three or four days' beard sitting next to me on the stamped metal bottom of the open back part of a pickup truck. Bouncing along. Dipping and rising and rolling on these rotten springs like a boat. Out the back of the truck the city of San Francisco is bouncing down the hill, all those endless staggers of bay windows, slums with a view, bouncing and streaming down the hill. One after another, electric signs with neon martini glasses lit up on them, the San Francisco symbol of "bar"—thousands of neon-magenta martini glasses bouncing and streaming down the hill, and beneath them hundreds, thousands of people wheeling around to look at this freaking crazed truck we're in, their white faces erupting from their lapels like marshmallows—streaming and bouncing down the hill—and God knows they've got plenty to look at.

That's why it strikes me as funny when Cool Breeze says very seriously over the whole roar of the thing, "I don't know—when Kesey gets out I don't know if I can come around the Warehouse."

"Why not?"

"Well, like the cops are going to be coming around like all feisty, and I'm on probation, so I don't know."

Well, that's good thinking there, Cool Breeze. Don't rouse the bastids. Lie low—like right now. Right now Cool Breeze is so terrified of the law he is sitting up in plain view of thousands of already startled citizens wearing some kind of Seven Dwarfs Black Forest gnome's hat covered in feathers and fluorescent colors. Kneeling in the truck, facing us, also in plain view, is a half-Ottawa Indian girl named Lois Jennings, with her head thrown back and a radiant look on her face. Also a blazing silver disk in the middle of her forehead alternately exploding with light when the sun hits it or sending off rainbows from the defraction lines in it. And, oh yeah, there's a long-barreled Colt .45 revolver in her hand, only nobody on the street can tell it's a cap pistol as she pegs away, kheeew, kheeew, at the erupting marshmallow faces like Debra Paget in … in …

—Kesey's coming out of jail!

Two more things they are looking at out there are a sign on the rear bumper reading "Custer Died for Your Sins" and, at the wheel, Lois's enamorado Stewart Brand, a thin blond guy with a blazing disk on his forehead too, and a whole necktie made of Indian beads. No shirt, however, just an Indian bead necktie on bare skin and a white butcher's coat with medals from the King of Sweden on it.

Here comes a beautiful one, attaché case and all, the day-is-done resentful look and the … shoes—how they shine!—and what the hell are these beatnik ninnies—and Lois plugs him in the old marshmallow and he goes streaming and bouncing down the hill …

And the truck heaves and billows, blazing silver red and Day-Glo, and I doubt seriously, Cool Breeze, that there is a single cop in all of San Francisco today who does not know that this crazed vehicle is a guerrilla patrol from the dread LSD.

The cops now know the whole scene, even the costumes, the jesuschrist strung-out hair, Indian beads, Indian headbands, donkey beads, temple bells, amulets, mandalas, god's-eyes, fluorescent vests, unicorn horns, Errol Flynn dueling shirts—but they still don't know about the shoes. The heads have a thing about shoes. The worst are shiny black shoes with shoelaces in them. The hierarchy ascends from there, although practically all lowcut shoes are unhip, from there on up to the boots the heads like, light, fanciful boots, English boots of the mod variety, if that is all they can get, but better something like hand-tooled Mexican boots with Caliente Dude Triple A toes on them. So see the FBI—black—shiny—laced up—FBI shoes—when the FBI finally grabbed Kesey—

There is another girl in the back of the truck, a dark little girl with thick black hair, called Black Maria. She looks Mexican, but she says to me in straight soft Californian:

"When is your birthday?"

"March 2."

"Pisces," she says. And then: "I would never take you for a Pisces."

"Why?"

"You seem too … solid for a Pisces."

But I know she means stolid. I am beginning to feel stolid. Back in New York City, Black Maria, I tell you, I am even known as something of a dude. But somehow a blue silk blazer and a big tie with clowns on it and … a … pair of shiny lowcut black shoes don't set them all to doing the Varsity Rag in the head world in San Francisco. Lois picks off the marshmallows one by one; Cool Breeze ascends into the innards of his gnome's hat; Black Maria, a Scorpio herself, rummages through the Zodiac; Stewart Brand winds it through the streets; paillettes explode—and this is nothing special, just the usual, the usual in the head world of San Francisco, just a little routine messing up the minds of the citizenry en route, nothing more than psyche food for beautiful people, while giving some guy from New York a lift to the Warehouse to wait for the Chief, Ken Kesey, who is getting out of jail.

ABOUT ALL I KNEW ABOUT KESEY AT THAT POINT WAS THAT HE was a highly regarded 31-year-old novelist and in a lot of trouble over drugs. He wrote One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (1962), which was made into a play in 1963, and Sometimes a Great Notion (1964). He was always included with Philip Roth and Joseph Heller and Bruce Jay Friedman and a couple of others as one of the young novelists who might go all the way. Then he was arrested twice for possession of marijuana, in April of 1965 and January of 1966, and fled to Mexico rather than risk a stiff sentence. It looked like as much as five years, as a second offender. One day I happened to get hold of some letters Kesey wrote from Mexico to his friend Larry McMurtry, who wrote Horseman, Pass By, from which the movie Hud was made. They were wild and ironic, written like a cross between William Burroughs and George Ade, telling of hideouts, disguises, paranoia, fleeing from cops, smoking joints and seeking satori in the Rat lands of Mexico. There was one passage written George Ade—fashion in the third person as a parody of what the straight world back there in the U.S.A. must think of him now:

"In short, this young, handsome, successful, happily-married-three-lovely-children father was a fear-crazed dope fiend in flight to avoid prosecution on three felonies and god knows how many misdemeanors and seeking at the same time to sculpt a new satori from an old surf—in even shorter, mad as a hatter.

"Once an athlete so valued he had been given the job of calling signals from the line and risen into contention for the nationwide amateur wrestling crown, now he didn't know if he could do a dozen pushups. Once possessor of a phenomenal bank account and money waving from every hand, now it was all his poor wife could do to scrape together eight dollars to send as getaway money to Mexico. But a few years previous he had been listed in Who's Who and asked to speak at such auspicious gatherings as the Wellesley Club in Dah-la and now they wouldn't even allow him to speak at a VDC [Vietnam Day Committee] gathering. What was it that had brought a man so high of promise to so low a state in so short a time? Well, the answer can be found in just one short word, my friends, in just one all-well-used syllable:

"Dope!

"And while it may be claimed by some of the addled advocates of these chemicals that our hero is known to have indulged in drugs before his literary success, we must point out that there was evidence of his literary prowess well before the advent of the so-called psychedelic into his life but no evidence at all of any of the lunatic thinking that we find thereafter!"

To which he added:

"(oh yea, the wind hums

time ago—time ago—

the rafter drums and the walls see

… and there's a door to that bird

in the sa-a-a-apling sky

time ago by—

Oh yeah the surf giggles

time ago time ago

of under things killed when

bad was banished and all the

doors to the birds vanished

time ago then.)"

I got the idea of going to Mexico and trying to find him and do a story on Young Novelist Real-Life Fugitive. I started asking around about where he might be in Mexico. Everybody on the hip circuit in New York knew for certain. It seemed to be the thing to know this summer. He is in Puerto Vallarta. He is in Ajijic. He is in Oaxaca. He is in San Miguel de Allende. He is in Paraguay. He just took a steamboat from Mexico to Canada. And everyone knew for certain.

I was still asking around when Kesey sneaked back into the U.S. in October and the FBI caught up with him on the Bayshore freeway south of San Francisco. An agent chased him down an embankment and caught him and Kesey was in jail. So I flew to San Francisco. I went straight to the San Mateo County jail in Redwood City and the scene in the waiting room there was more like the stage door at the Music Box Theatre. It was full of cheerful anticipation. There was a young psychologist there, Jim Fadiman—Clifton Fadiman's nephew, it turned out—and Jim and his wife Dorothy were happily stuffing three I Ching coins into the spine of some interminable dense volume of Oriental mysticism and they asked me to get word to Kesey that the coins were in there. There was also a little roundfaced brunette named Marilyn who told me she used to be a teenie grouper hanging out with a rock ‘n' roll group called The Wild Flowers but now she was mainly with Bobby Petersen. Bobby Petersen was not a musician. He was a saint, as nearly as I could make out. He was in jail down in Santa Cruz trying to fight a marijuana charge on the grounds that marijuana was a religious sacrament for him. I didn't figure out exactly why she was up here in the San Mateo jail waiting room instead except that it was like a stage door, as I said, with Kesey as the star who was still inside.

There was a slight hassle with the jailers over whether I was to get in to see him or not. The cops had nothing particularly to gain by letting me in. A reporter from New York—that just meant more publicity for this glorified beatnik. That was the line on Kesey. He was a glorified beatnik up on two dope charges, and why make a hero out of him. I must say that California has smooth cops. They all seem to be young, tall, crewcut, blond, with bleached blue eyes, like they just stepped out of a cigarette ad. Their jailhouses don't look like jailhouses, at least not the parts the public sees. They are all blond wood, fluorescent lights and filing-cabinet-tan metal, like the Civil Service exam room in a new Post Office building. The cops all speak soft Californian and are neat and correct as an ice cube. By the book; so they finally let me in to see Kesey during visiting hours. I had ten minutes. I waved goodbye to Marilyn and the Fadimans and the jolly scene downstairs and they took me up to the third floor in an elevator.

The elevator opened right onto a small visiting room. It was weird. Here was a lineup of four or five cubicles, like the isolation booths on the old TV quiz shows, each one with a thick plate-glass window and behind each window a prisoner in a prison blue workshirt. They were lined up like haddocks on ice. Outside each window ran a counter with a telephone on it. That's what you speak over in here. A couple of visitors are already hunched over the things. Then I pick out Kesey.

He is standing up with his arms folded over his chest and his eyes focused in the distance, i.e., the wall. He has thick wrists and big forearms, and the way he has them folded makes them look gigantic. He looks taller than he really is, maybe because of his neck. He has a big neck with a pair of sternocleido-mastoid muscles that rise up out of the prison workshirt like a couple of dock ropes. His jaw and chin are massive. He looks a little like Paul Newman, except that he is more muscular, has thicker skin, and he has tight blond curls boiling up around his head. His hair is almost gone on top, but somehow that goes all right with his big neck and general wrestler's build. Then he smiles slightly. It's curious, he doesn't have a line in his face. After all the chasing and hassling—he looks like the third week at the Sauna Spa; serene, as I say.

Then I pick up my telephone and he picks up his—and this is truly Modern Times. We are all of twenty-four inches apart, but there is a piece of plate glass as thick as a telephone directory between us. We might as well be in different continents, talking over Videophone. The telephones are very crackly and lo-fi, especially considering that they have a world of two feet to span. Naturally it was assumed that the police monitored every conversation. I wanted to ask him all about his fugitive days in Mexico. That was still the name of my story, Young Novelist Fugitive Eight Months in Mexico. But he could hardly go into that on this weird hookup, and besides, I had only ten minutes. I take out a notebook and start asking him—anything. There had been a piece in the paper about his saying it was time for the psychedelic movement to go "beyond acid," so I asked him about that. Then I started scribbling like mad, in shorthand, in the notebook. I could see his lips moving two feet away. His voice crackled over the telephone like it was coming from Brisbane. The whole thing was crazy. It seemed like calisthenics we were going through.

"It's my idea," he said, "that it's time to graduate from what has been going on, to something else. The psychedelic wave was happening six or eight months ago when I went to Mexico. It's been growing since then, but it hasn't been moving. I saw the same stuff when I got back as when I left. It was just bigger, that was all—" He talks in a soft voice with a country accent, almost a pure country accent, only crackling and rasping and cheese-grated over the two-foot hookup, talking about—

"—there's been no creativity," he is saying, "and I think my value has been to help create the next step. I don't think there will be any movement off the drug scene until there is something else to move to—"

—all in a plain country accent about something—well, to be frank, I didn't know what in the hell it was all about. Sometimes he spoke cryptically, in aphorisms. I told him I had heard he didn't intend to do any more writing. Why? I said.

"I'd rather be a lightning rod than a seismograph," he said.

He talked about something called the Acid Test and forms of expression in which there would be no separation between himself and the audience. It would be all one experience, with all the senses opened wide, words, music, lights, sounds, touch—lightning.

"You mean on the order of what Andy Warhol is doing?" I said.

… pause. "No offense," says Kesey, "but New York is about two years behind."

He said it very patiently, with a kind of country politeness, as if … I don't want to be rude to you fellows from the City, but there's been things going on out here that you would never guess in your wildest million years, old buddy …

THE TEN MINUTES WERE UP AND I WAS OUT OF THERE. I HAD gotten nothing, except my first brush with a strange phenomenon, that strange up-country charisma, the Kesey presence. I had nothing to do but kill time and hope Kesey would get out on bail somehow and I could talk to him and get the details on Novelist Fugitive in Mexico. This seemed like a very long shot at this time, because Kesey had two marijuana charges against him and had already jumped the country once.

So I rented a car and started making the rounds in San Francisco. Somehow my strongest memories of San Francisco are of me in a terrific rented sedan roaring up hills or down hills, sliding on and off the cable-car tracks. Slipping and sliding down to North Beach, the fabled North Beach, the old fatherland bohemia of the West Coast, always full of Big Daddy So-and-so and Costee Plusee and long-haired little Wasp and Jewish buds balling spade cats—and now North Beach was dying. North Beach was nothing but tit shows. In the famous Beat Generation HQ, the City Lights bookstore, Shig Murao, the Nipponese panjandrum of the place, sat glowering with his beard hanging down like those strands of furze and fern in an architect's drawing, drooping over the volumes of Kahlil Gibran by the cash register while Professional Budget Finance Dentists here for the convention browsed in search of the beatniks between tit shows. Everything was The Topless on North Beach, strippers with their breasts enlarged with injections of silicone emulsion.

The action—meaning the hip cliques that set the original tone—the action was all over in Haight-Ashbury. Pretty soon all the bellwethers of a successful bohemia would be there, too, the cars going through, bumper to bumper, with everbody rubber-necking, the tour buses going through "and here … Home of the Hippies … there's one there," and the queers and spade hookers and bookstores and boutiques. Everything was Haight-Ashbury and the acid heads.

But it was not just North Beach that was dying. The whole old-style hip life—jazz, coffee houses, civil rights, invite a spade for dinner, Vietnam—it was all suddenly dying, I found out, even among the students at Berkeley, across the bay from San Francisco, which had been the heart of the "student-rebellion" and so forth. It had even gotten to the point that Negroes were no longer in the hip scene, not even as totem figures. It was unbelievable. Spades, the very soul figures of Hip, of jazz, of the hip vocabulary itself, man and like and dig and baby and scarf and split and later and so fine, of civil rights and graduating from Reed College and living on North Beach, down Mason, and balling spade cats—all that good elaborate petting and patting and pouring soul all over the spades—all over, finished, incredibly.

So I was starting to get the trend of all this heaving and convulsing in the bohemian world of San Francisco. Meantime, miraculously, Kesey's three young lawyers, Pat Hallinan, Brian Rohan, and Paul Robertson, were about to get Kesey out on bail. They assured the judges, in San Mateo and San Francisco, that Mr. Kesey had a very public-spirited project in mind. He had returned from exile for the express purpose of calling a huge meeting of heads and hippies at Winterland Arena in San Francisco in order to tell The Youth to stop taking LSD because it was dangerous and might french fry their brains, etc. It was going to be an "acid graduation" ceremony. They should go "beyond acid." That was what Kesey had been talking to me about, I guess. At the same time, six of Kesey's close friends in the Palo Alto area had put their homes up as security for a total of $35,000 bail with the San Mateo County court. I suppose the courts figured they had Kesey either way. If he jumped bail now, it would be such a dirty trick on his friends, costing them their homes, that Kesey would be discredited as a drug apostle or anything else. If he didn't, he would be obliged to give his talk to The Youth—and so much the better. In any case, Kesey was coming out.

This script was not very popular in Haight-Ashbury, however. I soon found out that the head life in San Francisco was already such a big thing that Kesey's return and his acid graduation plan were causing the heads' first big political crisis. All eyes were on Kesey and his group, known as the Merry Pranksters. Thousands of kids were moving into San Francisco for a life based on LSD and the psychedelic thing. Thing was the major abstract word in Haight-Ashbury. It could mean anything, isms, life styles, habits, leanings, causes, sexual organs; thing and freak; freak referred to styles and obsessions, as in "Stewart Brand is an Indian freak" or "the zodiac—that's her freak," or just to heads in costume. It wasn't a negative word. Anyway, just a couple of weeks before, the heads had held their first big "be-in" in Golden Gate Park, at the foot of the hill leading up into Haight-Ashbury, in mock observance of the day LSD became illegal in California. This was a gathering of all the tribes, all the communal groups. All the freaks came and did their thing. A head named Michael Bowen started it, and thousands of them piled in, in high costume, ringing bells, chanting, dancing ecstatically, blowing their minds one way and another and making their favorite satiric gestures to the cops, handing them flowers, burying the bastids in tender fruity petals of love. Oh christ, Tom, the thing was fantastic, a freaking mind-blower, thousands of high-loving heads out there messing up the minds of the cops and everybody else in a fiesta of love and euphoria. Even Kesey, who was still on the run then, had brazened on in and mingled with the crowd for a while, and they were all one, even Kesey—and now all of a sudden here he is, in the hands of the FBI and other supercops, the biggest name in The Life, Kesey, announcing that it is time to "graduate from acid." And what the hell is this, a copout or what? The Stop Kesey movement was beginning even within the hip world.

We pull up to the Warehouse in the crazed truck and—well, for a start, I begin to see that people like Lois and Stewart and Black Maria are the restrained, reflective wing of the Merry Pranksters. The Warehouse is on Harriet Street, between Howard and Folsom. Like most of San Francisco, Harriet Street is a lot of wooden buildings with bay windows all painted white. But Harriet Street is in San Francisco's Skid Row area, and despite all the paint, it looks like about forty winos crawled off in the shadows and died and turned black and bloated and exploded, sending forth a stream of spirochetes that got into every board, every strip, every crack, every splinter, every flecking flake of paint. The Warehouse actually turns out to be the ground-floor garage of an abandoned hotel. Its last commercial use was as a pie factory. We pull up to the garage and there is a panel truck parked just outside, painted in blue, yellow, orange, red Day-Glo, with the word BAM in huge letters on the hood. From out the black hole of the garage comes the sound of a record by Bob Dylan with his raunchy harmonica and Ernest Tubb voice raunching and rheuming in the old jack-legged chants—

Inside is a huge chaotic space with what looks at first in the gloom like ten or fifteen American flags walking around. This turns out to be a bunch of men and women, most of them in their twenties, in white coveralls of the sort airport workers wear, only with sections of American flags sewn all over, mostly the stars against fields of blue but some with red stripes running down the legs. Around the side is a lot of theater scaffolding with blankets strewn across like curtains and whole rows of uprooted theater seats piled up against the walls and big cubes of metal debris and ropes and girders.

One of the blanket curtains edges back and a little figure vaults down from a platform about nine feet up. It glows. It is a guy about five feet tall with some sort of World War I aviator's helmet on … glowing with curves and swirls of green and orange. His boots, too; he seems to be bouncing over on a pair of fluorescent globes. He stops. He has a small, fine, ascetic face with a big mustache and huge eyes. The eyes narrow and he breaks into a grin.

"I just had an eight-year-old boy up there," he says.

Then he goes into a sniffling giggle and bounds, glowing, over into a corner, in among the debris.

Everybody laughs. It is some kind of family joke, I guess. At least I am the only one who scans the scaffolding for the remains.

"That's the Hermit." Three days later I see he has built a cave in the corner.

A bigger glow in the center of the garage. I make out a school bus … glowing orange, green, magenta, lavender, chlorine blue, every fluorescent pastel imaginable in thousands of designs, both large and small, like a cross between Fernand Léger and Dr. Strange, roaring together and vibrating off each other as if somebody had given Hieronymous Bosch fifty buckets of Day-Glo paint and a 1939 International Harvester school bus and told him to go to it. On the floor by the bus is a 15-foot banner reading ACID TEST GRADUATION, and two or three of the Flag People are working on it. Bob Dylan's voice is raunching and rheuming and people are moving around, and babies are crying. I don't see them but they are somewhere in here, crying. Off to one side is a guy about 40 with a lot of muscles, as you can see because he has no shirt on—just a pair of khakis and some red leather boots on and his hell of a build—and he seems to be in a kinetic trance, flipping a small sledge hammer up in the air over and over, always managing to catch the handle on the way down with his arms and legs kicking out the whole time and his shoulders rolling and his head bobbing, all in a jerky beat as if somewhere Joe Cuba is playing "Bang Bang" although in fact even Bob Dylan is no longer on and out of the speaker, wherever it is, comes some sort of tape with a spectral voice saying:

" … The Nowhere Mine … we've got bubble-gum wrappers …" some sort of weird electronic music behind it, with Oriental intervals, like Juan Carrillo's music: " … We're going to jerk it out from under the world … working in the Nowhere Mine … this day, every day …"

One of the Flag People comes up.

"Hey, Mountain Girl! That's wild!"

Mountain Girl is a tall girl, big and beautiful with dark brown hair falling down to her shoulders except that the lower two-thirds of her falling hair looks like a paint brush dipped in cadmium yellow from where she dyed it blond in Mexico. She pivots and shows the circle of stars on the back of her coveralls.

"We got ‘em at a uniform store," she says. "Aren't they great! There's this old guy in there, says, ‘Now, you ain't gonna cut them flags up for costumes, are you?' And so I told him, ‘Naw, we're gonna git some horns and have a parade.' But you see this? This is really why we got'em."

She points to a button on the coveralls. Everybody leans in to look. A motto is engraved on the bottom in art nouveau curves: "Can't Bust'Em."

Can't Bust'Em! … and about time. After all the times the Pranksters have gotten busted, by the San Mateo County cops, the San Francisco cops, the Mexicale Federale cops, FBI cops, cops cops cops cops …

And still the babies cry. Mountain Girl turns to Lois Jennings.

"What do Indians do to stop a baby from crying?"

"They hold its nose."

"Yeah?"

"They learn."

"I'll try it … it sounds logical …" And Mountain Girl goes over and picks up her baby, a four-month-old girl named Sunshine, out of one of those tube-and-net portable cribs from behind the bus and sits down in one of the theater seats. But instead of the Indian treatment she unbuttons the Can't Bust'Em coveralls and starts feeding her.

" … The Nowhere Mine … Nothing felt and screamed and cried …" brang tweeeeeeng " … and I went back to the Nowhere Mine …"

The sledge-hammer juggler rockets away—

"Who is that?"

"That's Cassady."

This strikes me as a marvelous fact. I remember Cassady. Cassady, Neal Cassady, was the hero, "Dean Moriarty," of Jack Kerouac's On the Road, the Denver Kid, a kid who was always racing back and forth across the U.S. by car, chasing, or outrunning, "life," and here is the same guy, now 40, in the garage, flipping a sledge hammer, rocketing about to his own Joe Cuba and—talking. Cassady never stops talking. But that is a bad way to put it. Cassady is a monologuist, only he doesn't seem to care whether anyone is listening or not. He just goes off on the monologue, by himself if necessary, although anyone is welcome aboard. He will answer all questions, although not exactly in that order, because we can't stop here, next rest area 40 miles, you understand, spinning off memories, metaphors, literary, Oriental, hip allusions, all punctuated by the unlikely expression, "you understand—"

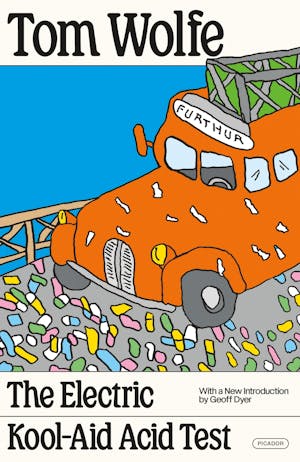

THE ELECTRIC KOOL-AID ACID TEST. Copyright © 1968 by Tom Wolfe.