Preface

My dear Croker,

I wish you would think seriously of the History of the Reign of Terror. I do not mean a pompous, philosophical history, but a mixture of biography, facts and gossip: a diary of what really took place with the best authenticated likenesses of the actors.

Ever yours,

Robert Peel1

Soon after he received this letter from his friend Sir Robert Peel, the once and future Tory prime minister, John Wilson Croker packed his bags for a seaside holiday. Although he was a prominent literary and political journalist and was hoping to work as he sat on the beach, Croker packed none of his collection of rare and fascinating books about the French Revolution that are now one of the glories of the British Library. He took with him only the list of those condemned to death during the Reign of Terror.2 He perused it against the rhythmic sound of waves breaking on the shore.

Twenty-two impoverished women, many of them widows, convicted of forwarding "the designs of the fanatics, aristocrats, priests and other agents of England," guillotined.

Nine private soldiers convicted of "pricking their own eyes with pins, and becoming by this cowardly artifice unable to bear arms," guillotined.

Jean Baptiste Henry, aged eighteen, journeyman tailor, convicted of sawing down a tree of liberty, guillotined.

Henrietta Frances de Marbœuf, aged fifty-five, convicted of hoping for the arrival in Paris of the Austrian and Prussian armies and of hoarding provisions for them, guillotined.

James Duchesne, aged sixty, formerly a servant, since a broker; John Sauvage, aged thirty-four, gunsmith; Frances Loizelier, aged forty-seven, milliner; Mélanie Cunosse, aged twenty-one, milliner; Mary Magdalen Virolle, aged twenty-five, hairdresser: all convicted for writing, guillotined.

Geneviève Gouvon, aged seventy-seven, seamstress, convicted of "various conspiracies since the beginning of the Revolution," guillotined.

Francis Bertrand, aged thirty-seven, convicted of producing "sour wine injurious to the health of citizens," guillotined.

Mary Angelica Plaisant, another seamstress, guillotined for exclaiming, "A fig for the nation!"

Relaxing into his holiday, Croker continued reading through the long list of dubious charges against the several thousand victims of the Revolutionary Tribunal of Paris, from its institution on 10 March 1793 until the fall of Maximilien Robespierre on 27 July 1794. He compiled some grimly fascinating statistics: in the last five months of Robespierre's life, when he supposedly secured tyrannous power over France and the Revolution, 2,217 people were guillotined in Paris; but the total condemned to death in the eleven months preceding Robespierre's Reign of Terror was only 399. On the basis of these statistics, Croker concluded that the executions "grew gradually with the personal influence of Robespierre, and became enormous in proportion as he successively extinguished his rivals."3 In awed horror he recalled, "These things happened in our time—thousands are still living who saw them, yet it seems almost incredible that batches (fournées—such was the familiar phrase)—of sixty victims should be condemned in one morning by the same tribunal, and executed the same afternoon on the same scaffold."

Although Peel pressed his friend to write a popular and accessible book about the French Revolution, Croker never did so. When he got back from his holiday in 1835 he published his seaside musings in an article for the Quarterly Review. Here he acknowledged the enormity of the problem Robespierre still poses biographers: "The blood-red mist by which his last years were enveloped magnified his form, but obscured his features. Like the Genius of the Arabian tale, he emerged suddenly from a petty space into enormous power and gigantic size, and as suddenly vanished, leaving behind him no trace but terror."4

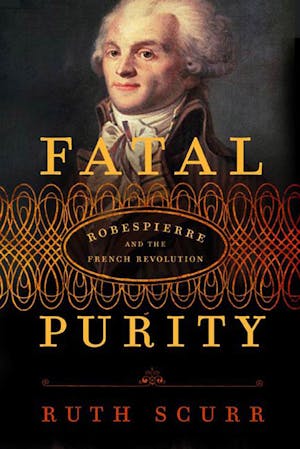

Copyright © 2006 by Ruth Scurr