DO NOT RETURN

JUNE 7, 1812

Early summer, in a time of war,

when the sea is a battleground

and ships are weapons,

I find myself on the deck of the Osnaburgh,

heading for Scotland.

Little separates me from the mail

and cargo in the ship’s hold.

I am like a letter stamped DO NOT RETURN,

being delivered to a future I cannot know.

I try to keep the shoreline in sight, as if this

will prevent the wind driving the sails.

But gradually, the land recedes into a thin line

and then is swallowed completely

by bruise-colored clouds.

I am left to feel

completely alone.

MEMORIES

The memory of my father’s face haunts me.

His mood was as dark as the sea when he put me on board.

My stepmother hadn’t even come to see me off,

nor had my brothers, who were away at school.

Only my sisters, Fanny and Claire, cried a little

as the ship pulled away.

At the thought of them I reach for the purse

that hangs at my waist.

It holds their letters and the coins Father gave me.

But my chilled fingers come away empty

and my despair sinks deeper.

The purse is gone.

It is an unpleasant reminder that I,

a fourteen-year-old girl traveling alone,

am easy prey for pickpockets and thieves.

I grip the rail tighter,

holding myself up on trembling legs.

How have things come this far?

THE FAMILY I LEAVE BEHIND

No one was kinder to me than Fanny.

She was only three years older than me,

but had been forced to be both mother and sister

since the day I was born,

because our mother had died.

From the earliest I can remember it was she alone

who wrapped soft, warm arms around me

and held me when I cried.

HERSCHEL’S COMET

Father used to tell me how he watched a comet with a tail of flame

hurl itself across the London sky

on the night that I was born.

That comet was like a messenger heralding a new era,

its path illuminating a line between old superstitions

and mankind’s growing understanding of the planets and stars.

But the almost impossible fact about that comet

was that it was discovered

by a woman.

Caroline Herschel was an astronomer,

self-trained

because women were barred from universities.

She toiled and labored

until she had named eight comets

and no one could deny she was a scientist.

Father gave me the belief that I could do anything

when he told me the story of the comet

that blazed across the London sky

on the night that I was born.

A CHILDHOOD OF POEMS

Father didn’t expect us to sew,

or play with dolls like other girls.

Instead he gave us the books our mother had written,

and encouraged us to read.

He taught us independence is admirable,

and imagination indispensable.

Fanny and I were allowed to stay up late

when Father’s friends came over to discuss science,

and politics, and literature.

My favorite friend was Mr. Coleridge,

who could make even Father laugh

with his game of making shadow creatures

dance on walls.

Then Mr. Coleridge would put down his hands

and his thoughts turned inward and dark,

and his liquid voice recited poetry

spooky enough to summon witches down our chimney.

But all of this ended when Father remarried.

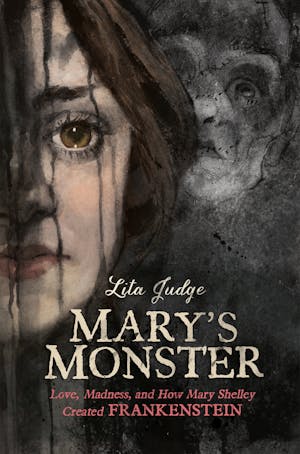

Copyright © 2018 by Lita Judge