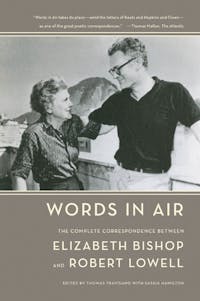

Words in Air

The Complete Correspondence Between Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell

Download image

Download image

ISBN10: 0374531897

ISBN13: 9780374531898

Trade Paperback

928 Pages

$35.00

CA$47.50

A Washington Post 10 Best Books of the Year

A Guardian Best Books of the Year

A Los Angeles Times Favorite Book of the Year

Robert Lowell once remarked in a letter to Elizabeth Bishop that "you ha[ve] always been my favorite poet and favorite friend." The feeling was mutual. Bishop said that conversation with Lowell left her feeling "picked up again to the proper table-land of poetry," and she once begged him, "Please never stop writing me letters—they always manage to make me feel like my higher self (I've been re-reading Emerson) for several days."

Neither ever stopped writing letters, from their first meeting in 1947 when both were young, newly launched poets until Lowell's death in 1977. The substantial, revealing—and often very funny—interchange that they produced stands as a remarkable collective achievement, notable for its sustained conversational brilliance of style, its wealth of literary history, its incisive snapshots and portraits of people and places, and its delicious literary gossip, as well as for the window it opens into the unfolding human and artistic drama of two of America's most beloved and influential poets.

Reviews

Praise for Words in Air

"Thomas Travisano, one of Bishop's most incisive commentators, has now joined with Saskia to issue in a single book the moving thirty-year correspondence between Bishop and Lowell, revealing how this long literary and personal friendship developed and evolved, underwent painful strains, and always recovered . . . In absorbing this long relationship, the reader is greatly helped by the detailed annotation of the letters: Travisano and Hamilton have minutely identified every poem, every article, every person, every event mentioned by the poets . . . But beyond these descriptive tour de forces and compliments, beyond the literary and political gossip, the poet—especially as their lives grew increasing troubled by estrangements, separations, divorce, illnesses, and the deaths of friends—exchanged tender, serious, disturbed, and grieving messages."—Helen Vendler, The New York Review of Books

"Their surviving 459 letters, some surprisingly long (Bishop might elaborate hers over weeks, at times swearing she had written Lowell in her imagination), give us the closest view of these wounded creatures—his muscular, bull-in-a-china-shop intellect; her pained shyness and abject modesty, and a gaze like the gleam off a knife . . . The pleasures of this remarkable correspondence lie in the untiring way these poets entertained each other with the comic inadequacies of the world."—William Logan, The New York Times

"Words in Air gathers together more than 400 letters written over a 30-year span . . . What is absorbing and ultimately delightful; about the book is that we can read the back-and-forth between the two writers for the first time, as each responds to the other."—Dinitia Smith, The Wall Street Journal

"Most readers drawn to this wonderful correspondence—a book to linger and dawdle over for weeks—will already know at least a little about poets Elizabeth Bishop (1911-1979) and Robert Lowell (1917-1977). If you don't, first read at least a few of their poems. For Bishop, you might start with 'The Imaginary Iceberg' ('We'd rather have the iceberg than the ship'), the Kafkaesque vision called 'The Man-Moth' (inspired by a misprint of 'mammoth'), the celebrated villanelle 'One Art' ('The art of losing isn't hard to master'), 'Questions of Travel' ('Should we have stayed at home and thought of here?') and those two somewhat longer masterpieces 'The Moose' and 'Crusoe in England.' Together they make for some of the best poetry of the previous century. For Lowell, the choices are more difficult, as he wrote a great deal, frequently altered and revised already published work, and nearly always emphasized forcefulness and daring over classical finesse. The simplest course is to read his single, most admired book, Life Studies. This includes elegies for older writers such as George Santayana and Ford Madox Ford ('you were a kind man and you died in want'), poems about Lowell's relatives and ancestors, the famous 'Skunk Hour' (dedicated to Bishop) and several portraits of married life, such as '"'To Speak of Woe That Is in Marriage"' and 'Man and Wife': 'you were in your twenties, and I, / once hand on glass / and heart in mouth, / outdrank the Rahvs in the heat / of Greenwich Village. Fainting at your feet.' The Rahvs? Philip Rahv was the longtime editor of Partisan Review, as well as a powerful essayist and critic (see his classic analysis of American literature, 'Paleface and Redskin'). Among the myriad joys of Words in Air is that it re-creates the glorious heyday of the little magazines and quarterlies, that era when an article or a poem in the Kenyon or Hudson or Partisan Review could actually make a writer's reputation. It was also a time when gods like T.S. Eliot, Marianne Moore, Robert Frost and William Carlos Williams were still publishing and when half the young poets in America, including Lowell and Bishop, made the pilgrimage to St. Elizabeths Hospital, Washington's psychiatric haven, to spend an afternoon with Ezra Pound. Lowell and Bishop first met in 1947 at a party given by Randall Jarrell, the most feared and influential poetry critic of his time. Before long, Elizabeth and 'Cal' (as Lowell's friends called him) were corresponding regularly, discussing each other's work, their mutual acquaintances and almost everything, except their very deepest troubles: When distressed, Bishop sometimes drank to a state of hospitalization, while Lowell would periodically grow so manic that he required sedation and sanctuary in rest homes. Yet they never let their friendship lapse. Indeed, some people even thought they might marry. As Lowell once wrote to Bishop, 'Asking you is the might have been for me.' But "nothing was said, and like a loon that needs sixty feet, I believe, to take off from the water, I wanted time and space," and so the moment passed. One shudders to imagine the two as a wedded couple, especially since Bishop preferred women and Lowell rockily married three times. Both were absolutely superb letter writers, mutually admiring, each clearly striving to out-entertain the other. Yet even their literary gossip serves the greater purpose of inclusion, support and intimacy. For the most part, Lowell is the more dynamic of the two, the hot kid who lands the plum jobs, then prepares the way for the shyer Bishop to take over after him, as guest at an artist colony, as consultant at the Library of Congress, as Harvard professor. Lowell also writes the more dazzling letters, often peppering them with vivid pen portraits. Here is that previously mentioned artists' colony: 'No use describing Yaddo—rundown rose gardens, rotting cantaloupes, fountains, a bust of Dante with a hole in the head, sets called Gems of Ancient Literature, Masterpieces of the World, cracking dried up sets of Shakespeare, Ruskin, Balzac, Reminiscences of a Happy Life (the title of two different books), pseudo Poussins, pseudo Titians, pseudo Reynolds, pseudo and real English wood, portraits of the patroness, her husband, her lover, her children lit with tubular lights, like a church, like a museum . . . I'm delighted. Why don't you come?' With a deft sentence or two, Lowell can sum up the legendary Delmore Schwartz, William Empson, Theodore Roethke, Sylvia Plath and many others, including the razor-sharp Jarrell: 'I think of him as a fencer who has defeated and scarred all his opponents so that the sport has come to be almost abandoned, and Randall stands leaning on his foil, one shoulder a little lower than the other, unchallenged, invulnerable, deadly.' Surely, there is no better short description of John Berryman and his world than this: 'Saw John Berryman: utterly spooky, teaching brilliant classes, spending week-ends in the sanitarium, drinking, seedy, a little bald, often drunk, married to a girl of twenty-one from a Catholic parochial college, white, innocent beyond belief, just pregnant.' For much of her adult life Bishop lived away from the North American literary scene, primarily in Brazil with her beloved Lota de Macedo Soares. But this 'minor female Wordsworth,' as she calls herself, doesn't just write about landscape and nature. At one religious procession, she reports, a loud speaker orders the spectators to give 'a big hand for Our Lady of Fatima.' When asked what she would teach were she to come back to the University of Washington, Bishop dryly answers 'Remedial English.' From time to time, she even outdoes Lowell in pen portraiture: 'The local bookshop is run by an Englishman and his wife who is about 20 years older than he, very cute, really, with dyed bright pink hair. They play chess in the corner and very much dislike being interrupted by a customer. The other day a man I knew went in to buy a book and asked for it timidly. Hugh, the Englishman, said, "Good heavens, man! Can't you see I'm about to make a move?"' Oh, these letters are just so good! Reading Partisan Review in 1963, an annoyed Bishop asks Lowell, 'WHO wrote those idiotic movie reviews? I think she must be somebody's mistress?' (Answer: Pauline Kael.) After acquiring a mynah bird, Bishop announces that she's teaching it to say, 'I too dislike it'—the famous opening words of Marianne Moore's 'Poetry.' Both poets are insatiable readers. Bishop goes through 'just about all Dickens' in order to write a sonnet. Over the years she mentions her pleasure in the letters of Madame de Sévigné and Sydney Smith, the memoirs of Augustus Hare, Trollope's North America, Kipling's stories, Henry James's correspondence, and even Wittgenstein's Philosophical Investigations. Naturally, she reads The Group, the bestseller by her friend and Vassar classmate Mary McCarthy, but without much approval. Lowell is equally impressive. In bed for three days with a cold, he devours Thomas Carlyle's mammoth French Revolution: 'Overpowering, and almost as good as Moby Dick when you give in to it. Our century really can't match the best Victorians for nonfictional prose.' He studies the ancient Greek tragedies—one sometimes forgets that Lowell majored in classics—and boldly attempts English versions of many of the great poems of world literature (see the brilliant and sometimes maddeningly perverse Imitations). Unsurprisingly, Bishop agrees when Lowell says, 'I wonder if you ever found reading and writing curiously self-sufficient. There are times when one hardly needs people.' Not that these two are unsociable. Lowell confesses, like many a teenager, 'I am now on my second month of contact lenses and feel a new man.' Bishop unashamedly pulls all the strings she can to get a young Brazilian into Harvard (without success). And they can be blunt with each other too. When, in The Dolphin, Lowell cruelly alters the letters of his second wife, Elizabeth Hardwick, causing great hurt, Bishop comes right out and lets him have it: 'Art just isn't worth that much.' Later, when he's been going on about mortality and the passage of the years, she writes: 'I am now going to be very impertinent and aggressive. Please, please don't talk about old age so much, my dear old friend! You are giving me the creeps.' When Lowell finally admits to feeling guilty about The Dolphin, she softens the blow: 'We all have irreparable and awful actions on our consciences—that's really all I can say now. I do, I know. I just try to live without blaming myself for them every day, at least—every day, I should say—the nights take care of guilt sufficiently.' Well, I just can't praise Words in Air enough. As Lowell and Bishop's friend Randall Jarrell used to say: Anybody who cares about poetry will want to read it."—Michael Dirda, The Washington Post Book World

"In 1961, Elizabeth Bishop wrote Robert Lowell about Madame de Sévigné, France's venerated master of the art of letter writing: 'Have you ever read her? She is marvelous, and the wonder is that the letters survived, and are so much better than most things written on purpose.' There's a sweet, self-conscious irony there: Bishop's own letters were exquisitely written and radiant with purpose, never more so than when she addressed Lowell, who took the medium as seriously as she did. The poets met in 1947 at a dinner in New York hosted by their mutual friend Randall Jarrell, a party the painfully shy Bishop later said she was 'almost too scared to go to.' They bonded immediately and commenced a virtuosic epistolary duet that ended only with Lowell's death in 1977. A new collection of their complete correspondence, edited by Thomas Travisano with Saskia Hamilton, is not only an intimate, detailed history of American literary life in the postwar era, it's also an exhilarating document on the art of friendship, crafted with exceptional subtlety by a pair of masters . . . Words in Air makes an invaluable contribution to American literary scholarship, as most of the letters here have never been published before; yet it is something more. By devoting a single volume to the letters between the pair in chronological order, the editors have re-created a lifelong conversation that is intensely moving and readable. The book is good for dipping into, but once the reader has taken the dip, it's hard to stop reading. In addition to fascinating exchanges about their work, the volume abounds in witty, trenchant views of events in the great world beyond literature. Bishop moved to Brazil in 1951 to set up housekeeping with her partner, visionary architect Lota de Macedo Soares, a Brazilian woman from an aristocratic background who resembled Lowell in many ways. Bishop's dispatches about the social upheavals in Brazil during the 16 years she lived there alternate between the brilliantly colorful and coolly ironic. Lowell, the public figure, frequently provides firsthand glimpses of American history. At John F. Kennedy's inauguration, he tells Bishop, he wrote in the guest book, '"Robert Lowell, happy that at long last the Goths have left the Whitehouse." Bobby Kennedy read it and said, "I guess we are the Visigoths."' Inevitably, Words in Air possesses a special appeal for readers of poetry. Incidental portraits flit through the pages; snapshots of lovable, madcap Marianne Moore and the pathetic wreckage of Ezra Pound are particularly moving. T.S. Eliot makes a surprising appearance in one of Lowell's letters as 'Elbows Eliot,' for his uninhibited dancing at a 'Charles River boatclub brawl.' Bishop's appraisals of her contemporaries tend to be subtly pointed, often amusing in their self-revelatory candor. On Allen Ginsberg, in 1968: 'I find him rather admirable, except for his writing!—but feel a little like an old-fashioned Southerner about the Negro—all right as long as he keeps his place' . . . What finally gives Words in Air its emotional heft is its long continuity, which endows its pages with the immediacy of life. Joys and sorrows and puzzlements jostle; great passions blaze and fade. In the last pages, the poets bury friends and colleagues with obituaries that are frank and sometimes moving. The satisfying constant is their devotion to each other. Lowell wrote Bishop in 1959: 'Oh we won't ever fall out, God help us! Aren't people difficult.' And they never did."—Jamie James, Los Angeles Times

"Here is all of it, all you wanted—and can take—of the epistolary 'words in air' passed over a 30-year period (1947-77) between two of the most gifted poets in our last century's latter half. The task of assembling and editing them has been fulfilled in an exemplary manner by Thomas Travisano, author of an excellent critical study of Elizabeth Bishop, and Saskia Hamilton, who three years ago admirably edited Robert Lowell's letters. In Travisano's useful introduction he correctly points out the 'sustained colloquial brilliance of style' found in the correspondence, and Hamilton has contributed much to the scrupulous fullness of annotation, helpfully placed at the bottom of the page. The edition prints more than 300 hitherto-unpublished letters . . . For all their difficulties—perhaps even because of them—each managed, with the spur given by the other, to rise in their letters to humorous, buoyant, and consistently ironical self-presentation. 'I have acquired a phony, spruce disillusioned tone—but it's only Washington,' Lowell informs Bishop as he goes about his poetry-consultant duties at the Library of Congress in 1948. Bishop, teaching at the University of Washington in 1966, describes her students to Lowell: 'The boys are all over six feet—some girls are, too—and the girls have huge legs.' She had been warned by a friend 'about the bosom in the front row—but not about the large bare knee that starts creeping up over the edge of the table.' Such are two minor examples of the creative spirit everywhere to be found in the exchanges . . . There is no need to decide who was the superior letter writer, although Lowell's poetic gift for the original phrase or word is continually on display, and to dazzling effect . . . This volume takes its place, along with the correspondence between Edmund Wilson and Vladimir Nabokov, or Kingsley Amis and Philip Larkin, as consummate examples of wit, affection, and indeed—in the case of Bishop and Lowell—love."—William H. Pritchard, The Boston Globe

"Seeing each other more often would have given them less time to write, less to write about, and, since letters exist in reciprocal terms, less to read. As it is, Words in Air: The Complete Correspondence Between Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell, edited by Thomas Travisano, with Saskia Hamilton, takes up more than nine hundred pages. Like Victorians hungry for the next installment of a serialized novel, the two looked to each other's letters for sustenance. 'I've been reading Dickens, too,' Bishop wrote, as though confirming the scope and flavor of the correspondence, the 'abundance' and 'playfulness' that she ascribed to Dickens. The letters abound in Dickensian caricature, mostly gentle and humane. 'Several weird people have shown up here,' Lowell wrote from Washington, including a Dr. Swigget with a terza-rima rendering of Dante and an aspiring writer named 'Major Dyer, who takes Pound ice-cream, was a colleague of Patton's and teaches Margaret Truman fencing' . . . Words in Air may be the only book of its precise kind ever published: the lifelong correspondence between two artists of equal genius. Lowell and Bishop lived various, tumultuous lives, and yet sometimes it feels as if the outside world existed primarily to be fattened up for their letters . . . The letter billows onward for pages, detail upon detail, before ending with the announcement 'I have a TOUCAN— named Uncle Sam in a chauvinistic outburst.' When Bishop runs out of words, she draws a picture. When the occasion demands it, she switches ribbons on her typewriter and prints in red. The result is exhilarating, consistently so, for hundreds of pages at a time . . . This isn't writing: it's out-writing, and the spectacle of two brilliant out-writers grinding each other down over thirty years is astounding . . . Lowell writes to Bishop in November of that year, 'I have been sick again, and somehow even with you I shrink both from mentioning and not mentioning.' He goes on: 'These things come on with a gruesome, vulgar, blasting surge of "enthusiasm," one becomes a kind of man-aping balloon in a parade—then you subside and eat bitter coffee-grounds of dullness, guilt etc.' The metaphors capture the illness. The manic self is an inflated 'manaping balloon in a parade'—oversized, grotesque, dangerous. 'Man-aping' echoes the word 'mania,' while the flaccid self sits in recovery, eating morning-after 'coffee-grounds' of guilt. But the successful transformation of illness into metaphor is itself a sign of recovery. Lowell's recovery letters are among the most brilliant letters ever written, for the simple reason that the writing of them operates against such tragic stakes . . . In 1957, Bishop and Lota de Macedo Soares visited Lowell and Hardwick and their infant daughter, Harriet, in Maine. Lowell appears to have propositioned Bishop, suggesting that he visit her alone in Boston, New York, or Brazil. Bishop, in turn, told Hardwick. The letters that follow are grandiose on Lowell's end and strategic on Bishop's; the correspondence that had sustained so many remarkable exchanges now feels like a fraying rope over an abyss. Lowell, his mania still cresting, recasts the Maine misadventure as the unstoppering of a very old bottle. 'There's one bit of the past that I would like to get off my chest,' he writes: Do you remember how at the end of that long swimming and sunning Stonington day . . . we went up to, I think, the relatively removed upper Gross house and had one of those real fried New England dinners, probably awful. And we were talking about this and that about ourselves . . . and you said rather humorously yet it was truly meant, 'When you write my epitaph, you must say I was the loneliest person who ever lived' . . . I assumed that [it] would be a matter of time before I proposed and I half believed that you would accept. . . . The possible alternatives that life allows us are very few, often there must be none. . . . But asking you is the might have been for me, the one towering change, the other life that might have been had. How should one take this letter? It is, of course, what one would say. Yet it is also beautifully and truthfully said, although, as he writes in a postscript, 'too heatedly written with too many ands and so forth.' Bishop responds with the name of a good analyst in Cambridge. Reading this exchange is painful, but, oddly, it does not feel like eavesdropping. In a generally excellent introduction, Thomas Travisano, an English professor at Hartwick College, argues that Lowell's and Bishop's letters display 'the apparent absence of this interest in posterity on the part of two poets famous for their obsession with craft.' That's not so: even as fledglings, the two writers were the most posterity-obsessed literary creatures imaginable. No poet is obsessed with craft per se; craft is just a name for the mechanics of immortality. Travisano quotes the poet and critic Tom Paulin: 'The merest suspicion that the writing is aiming beyond the addressee at posterity freezes a letter's immediacy and destroys its spirit.' And yet what makes these letters so fascinating is their hawk's eye on immortality, even in the midst of lives lived fully, often sloppily. Writers like Lowell and Bishop are more human, sincere, candid—more genuine—the more ambitious they are."—Dan Chiasson, The New Yorker

"Words in Air allows us to experience the peculiar rhythm of the Bishop-Lowell relationship, a relationship conducted almost exclusively through the mail. The letters are assiduously but unobtrusively annotated by Thomas Travisano and Saskia Hamilton, and sometimes the dullest letters are also the most weirdly revealing . . . Words in Air is a sad, fascinating book by two great artists."—James Longenbach, The Nation

"They seem at times a bipolar pair, his manic output matched by her depressive reticence. 'I've always felt that I've written poetry more by not writing it than writing it,' Bishop told Lowell. But what Words in Air makes clear is that their poetry developed in tandem: they borrowed and stole from each other, made revisions according to the other's advice, tested and discarded poems after consultation, and (perhaps most importantly) wrote to satisfy the towering expectations each poet had for the other. They remind one in many ways (and sometimes reminded themselves) of Coleridge and Wordsworth, though a closer analogy might be to Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. One can easily imagine Lowell putting his unmade bed on the wall and calling it art . . . Some of the most interesting pages in Words in Air are shoptalk: two smart and ambitious poets seeking to position their own work amid competing models . . . Indeed, in the back-and-forth of these letters, we can see a kind of mutual schooling, as Lowell learned to trust the quick shifts and associative 'water-striding' of Bishop's descriptions, even as Bishop learned to honor the weight of her own life experiences."—Christopher Benfey, The New Republic

"Words in Air takes its place—amid the letters of Keats and Hopkins and Owen—as one of the great poetic correspondence."—Thomas Mallon, The Atlantic Monthly

"Friendships among poets can ignite sparks that flame into innovation. Consider those evenings at London's Mermaid Tavern with William Shakespeare, Ben Johnson, and Christopher Marlowe, sitting over their drinks, reinventing English verse; or William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge discussing politics and the sublime while strolling through the Grasmere Lake District; or Erza Pound and T. S. Eliot shoring up fragments of cultural ruins in the wake of World War I. Now Words in Air: The Complete Correspondence Between Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell, edited by Thomas Travisano with Saskia Hamilton, details the fruitful relationship of two of the late 20th century's most influential American poets . . . By including both sides of the conversation, Word in Air allows us to listen in on an intimate dialogue between two people who were arguably closer to each other than to any spouse or lover. This would be fascinating merely for the gossip—both were witty observers of the major literary and political figures who crossed their paths. More significantly, the correspondence clarifies their profound influence on each other's writing. As an added treat, their exchanges read like a gripping epistolary novel, dramatizing the trajectories of their troubled lives and brilliant careers against the backdrop of revolution in Brazil, John F. Kennedy's assassination, and the United States' involvement in Vietnam."—Phoebe Pettingell, The New Leader

"Helplessly lyrical till death did them part, Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell wrote so many wonderful letters and postcards to each other from 1947 through 1977 that it's amazing they ever found the time to publish their poetry. Words in Air, edited by Thomas Travisano with Saskia Hamilton, is their complete correspondence, 800 pages of epigrams and gossip, anxieties and epiphanies, logrolling and backbiting. There are lapses, of course: Lowell a manic-depressive, disappeared regularly into mental hospitals even after lithium had finally been prescribed for his bipolarity; Bishop, an alcoholic with autoimmune disorder, was forever breaking her bones. But they clearly savored each other's joy in language, odd-angled perspectives on the world, and unbuttoned intimacies. Their poetry—negotiating the tricky currents between public appearance and private self—profited from the cross-pollination. And just as Bishop, hiding out in Key West or Brazil, needed help in managing her career, Lowell in Boston or New York loved to network. So there is as much here about artists' colonies, teaching jobs, prize-giving, and Library of Congress stipends as there is about foreign countries, newborn children, cast-off lovers, and books in progress. Ezra Pound and Randall Jarrell show up so often you'd think they were parents. So do Marianne Moore and Partisan Review, which was the magazine of choice until Lowell and his wife Elizabeth Hardwick helped launch The New York Review of Books. Generous remarks are made about William Butler Yeats and George Santayana. Unkind things are said about Mary McCarthy, Phyllis McGinley, Kenneth Rexroth, and the Richards Wilbur and Eberhart. Ambivalence is expressed about Dylan Tomas and Simone de Beauvoir. Lowell will compare psychotherapy to the stirring-up of the bottom of an aquarium. Bishop, studying German, is amused to mote that 'Freud' means 'joy'—and sends Lowell a pair of lion's paws. In one of his last letters, before he dies of a heart attack in a taxicab in Manhattan, Lowell tells her, 'The intoxicating thing about rhyme ad meter is that they have nothing at all to do with truth, just as ballet steps are of no use on a hike.' Her lovely poem 'in memoriam' to him notes that he was always revising his work: '. . . And now—you've left / for good. You can't derange, or re-arrange, / your poems again. (But the Sparrows can their song.) / The words won't change again. Sad friend, you cannot change.'"—John Leonard, Harper's Magazine

"The easy flow of letters between Robert Lowell and Elizabeth Bishop, two of America's greatest 20th-century poets, began in 1947, and continued for 30 years. It was a correspondence, from first to last, of an unusual intensity. Although they were both New Englanders, their writerly temperaments were quite different. Bishop wrote and published her poetry slowly. She produced just three collections during her lifetime. She was sedulous, pernickety, quietly determined; she would work on poems for years. Her letters—models of gentle, hesitant statement—have something of those same qualities of tentativeness, restraint and minute attention. Her observations of the natural world are acute and fresh, but also objective, reaching beyond herself. The sound of the ego is turned well down. Lowell was much more prolific and more raucously in and of the world. His private life was tumultuous, his manic episodes legion. His observations of the world reflect his inner moods: charged, noisy, dramatic. The long-awaited 2003 edition of his collected poems runs to almost 1,000 pages. Bishop's collected poems is one-quarter of that length. They were never lovers, and although the much-married Lowell once considered proposing to Bishop, he never did. And yet the two admired each other more than they admired any other living poets and corresponded with an unusual seriousness of engagement. When Lowell wrote to Bishop he was, for once, not involved in an act of performance. When Bishop wrote to Lowell she knew that she was reading his poems more deeply, and with more responsible attention, than any other friend would ever dare to do. They knew no better—and no more fearless—critics than each other. Throughout his life, Lowell was a professional man of letters, who, as teacher and reviewer, stood at the centre of the literary world. Bishop, by contrast, often felt as if she were slightly lost, floating through a miasma of self-doubt. She moved around a lot. She spent 15 of her most productive years in Brazil and came to teaching late in her life. Socially tentative, she did not make waves in the world of poetry. Her reputation has grown, quietly, since her death in 1979. It was Lowell who was the roaring, self-lacerating, tragic king of the poetry jungle. These letters are full of delightfully acute observations about literary personalities and tell us much about the art of poetry in America—how poets think, behave and suffer. But the literary talk is constantly being interrupted by the smaller things of life and these wonderfully human documents are an appealing mix of the bookish and the everyday. Their turns of phrase are so savoursome they almost precipitate into poetry itself. From beginning to end, the two poets needed each other. 'Please never stop writing me letters,' Bishop once wrote to Lowell. 'They always manage to make me feel like my higher self.'"—The Economist

"Long anticipated, Words in Air: The Complete Correspondence Between Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell does not disappoint. It is a deep and abundant treasure-trove. I can't think of any correspondence between two major poets—and this one lasted some three decades—that can rival it. Lovers of the poetry of Elizabeth Bishop will relish the advent of this bulky 800-pager. Added to her equally extensive collected letters, One Art, these volumes allow us direct access to her private voice, and we can construct a vivid sense of Bishop as a person, in all her benign and complex aspects . . . These letters form the perfect accompaniment to one of the most precise, thoughtful and beautiful poetic oeuvres of modern times."—William Boyd, The Times Literary Supplement

"The correspondence of Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell makes for a very different book—not just because we now encounter two perspectives rather than one, a dialogue rather than monologue, but also because it portrays two artists inhabiting with, and making sense of a much vaster world. Their letters, invaluable for their insight into two such nimble, profound, and supple poetic minds, are no less important than Hughes's, but their tone is airer, their authors as eager to drop a bit of gossip as to analyze the merits of an unrhymed couplet . . . Anyone familiar with the poetry of Bishop and Lowell will be surprised by just how much these letters sound like Bishop and Lowell. Bishop's powers of description, which animate the poems of North and South and A Cold Spring, and especially her verse set in Brazil (where the poet settles in 1952), are everywhere apparent in her correspondence . . . Lowell, for his part, was a superb portraitist. Think of the lyrical, powerfully delineated character sketches in such works as Life Studies, Notebook, and The Dolphin. Should be surprised that Lowell's letters are also filled with portraits drawn with impeccable wit, mischief, and power? As an elegist, Lowell could sum up a life in a few masterful strokes, creating a picture that lingers in our minds like the lines of his greatest poems . . . One of the pleasures in reading this correspondence is viewing how each poet responded to the other's work. Lowell's critiques were mainly gentle. His comment's about Bishop's 'At the Fishhouses' in 1947 reflected the tone he would mainly take over the course of the next few decades . . . Bishop's criticisms of Lowell began modestly, too. But as the friendship bloomed, she increasingly revealed her hunger for precision, for the perfection of each word, each image in a poem. She expressed her displeasure at some of Lowell's very loose translations from the French and shuddered at his rendering of a famed Buenos Aires monument as a phallic image ('a white stone obelisk / rose like a phallus / without flesh or hair'), decrying not just the trend in contemporary poetry toward vulgarity, but also Lowell's use of cliché . . . I can't helping wondering, in our age of hurried e-mail transmission, with its flurries of sentence fragments and half phrases, if this long and storied epistolary tradition has come to an un fortunate end. If our great contemporary writers do indeed preserve their 'in' and 'sent' boxes, will these repositories one day reveal an artistry as rich and complete as do the great letter of earlier times? One can only hope."—Sudip Bose, The American Prospect

"Everyone knows that writers seek solitude. Without 'a room of one's own,' it's almost impossible to find the concentration and time for reflection that any creative work demands. Perhaps we're less familiar, though, with an equal need: the writer's thirst for artistic friendship, the company of a like-minded soul. Words in Air: The Complete Correspondence Between Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell is a brilliant testament to the pleasure and power of good company. This juicily thick volume collects 30 years of letters between two of the finest American poets of the last century. Watching their dawning friendship unfold is sheer delight, and because Bishop and Lowell became so devoted to entertaining each other with anecdotes, gossip, and marvelous bits of description, their letters offer some of the same delights as their richly evocative poems. Bishop describes a town in Maine so quiet 'its heart beats twice a day when the train goes through.' Lowell invites her to travel: 'Next year if our books were done and we had the cash, wouldn't you like to try Italy?' There's such life in these letters that the reader can't help but feel included in an intimate bond between two lively, vulnerable, and complex souls. Because their exchange stretches across decades, we watch these fast friends struggle, deepen, and change, and help to shape each other's work. Bishop, a private person and a reserved writer, follows Lowell's example to take more emotional risks. Lowell, a more public poet, reaches for a greater intimacy and a more relaxed and human voice. There's a long, respectful, charmed marriage of true minds here. These two lifetimes of mutual admiration make for irresistible reading."—Mark Doty, O, The Oprah Magazine

"Ah, the lost art of letter writing. Reading Words in Air: The Complete Correspondence Between Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell may make you pull out that old box of your good stationary. Never mind that these letters were written by two of the finest 20th-century poets; they'll inspire you. Forget e-mail. Try your hand at the sort of chatty missives many of us once loves writing and receiving."—The Indianapolis Star

"Everyone knows that writers seek solitude. Without 'a room of one's own,' it's almost impossible to find the concentration and time for reflection that any creative work demands. Perhaps we're less familiar though, with an equal need: the writer's thirst for artistic friendship, the company of a like-minded soul. Words in Air: The Complete Correspondence Between Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell is a brilliant testament to the pleasure and power of good company. This juicily thick volume collects 30 years of letters between two of the finest American poets of the last century. Watching their dawning friendship unfold is sheer delight, and because Bishop and Lowell became so devoted to entertaining each other with anecdotes, gossip, and marvelous bits of description, their letters offer some of the same delights as their richly evocative poems. Bishop describes a town in Maine so quiet 'its heart beats twice a day when the train goes through.' Lowell invites her to travel: 'Next year if our books were done and we had the cash, wouldn't you like to try Italy?' There's such life in these letters that the reader can't help but feel included in an intimate bond between two lively, vulnerable, and complex souls. Because their exchange stretches across decades, we watch these fast friends struggle, deepen, and change, and help to shape each other's work. Bishop, a private person and a reserved writer, follows Lowell's example to take more emotional risks. Lowell, a more public poet, reaches for a greater intimacy and a more relaxed and human voice. There's a long, respectful, charmed marriage of true minds here. These two lifetimes of mutual admiration make for irresistible reading."—Mark Doty, Reading Room

"The letters act as a kind of topographical map of the poets' personal and creative lives. They chart Lowell's periodic descents into psychosis, his three marriages, and his rise to become the most influential postwar poet in America. Of Bishop, living more quietly in Brazil, they offer elaborations on a sensibility that, combined with technical mastery, would cause her to win the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Award, and the National Book Critics Circle Award. The letters also offer vivid glimpses behind the scenes of what poet James Merrill has called 'her own instinctive, modest, lifelong impersonations of an ordinary woman.'"—Dominic Luxford, The Believer

"Though I have written a biography of Robert Lowell and have taught his and Elizabeth Bishop's poetry for over 30 years, I have found myself guiltily lugging this three-pound volume around with me for months now, unwilling to give it up. I would randomly open the book again and again to re-enter Lowell's Boston, Blue Hills, New York and Milgate Park, or Bishop's Key West, Washington, Ouro Preto, Rio de Janeiro, Seattle, Cam-bridge, North Haven and (finally) Boston, fascinated by the chance it has given me to listen in on their at once shy and witty conversations, insights, aperçus and distinctive ways of absorbing and reporting back on the sights, sounds and names of those around them, or what Lowell called the literary (and political) gossip of the moment . . . We owe a great debt to both Thomas Travisano and Saskia Hamilton for the staggering amount of editorial work that has gone into making this extraordinary correspondence available to us. There are thousands of footnotes, as well as a full chronology and a fascinating introduction, which make clear what Lowell or Bishop writes in the familiar shorthand of old friends who knew each other and each other's worlds, including contemporaries like Randall Jarrell and Adrienne Rich as well as such eminences as Pound, Eliot and Williams. And then, of course, there are the great dead whom both evoke, ranging from Aeschylus, Sappho and Cicero through Baudelaire, Emerson, Melville, Hawthorne, Hopkins, Yeats, Dostoyevsky and Turgenev . . . It is a marvelous collection, containing a thousand brilliant insights into so much that made up our world in the three decades between 1947 and 1977. It is a book—a musical instrument, really—for anyone interested in replaying the literature, poetry, history, culture and, yes, life lived in this explosive period in American history (North and South) when Lowell and Bishop created a world for which we are the richer."—Paul Mariani, America magazine

"Sometimes the imagined, hypostasized recipient of a letter may bear little resemblance to the actual person who opens it. And sometimes correspondents have the power to change the exchangers of letters into something much closer to what their mutual readers wish them to be. Words in Air: The Collected Letters of Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell, shows how much one can like the idea of someone better than the someone themselves, and how the fantasies built up by distance make for ravishing letters but greatly disappointing eventual meetings . . . The exchanges are almost constantly humorous and entertaining. This is partly because their authors are conscious of the special role of letters in literary life. Bishop offered a course at Radcliffe in 1971 on 'Personal Correspondence, Famous and Infamous,' and wrote to Lowell the year before that '[A] very good course could be given on poets and their letters—starting away back. There are so many good ones—Pope, Byron, Keats of course, Hopkins, Crane, Stevens, Marianne [Moore].' Many of Lowell's longer letters are hilarious comedy-of-manners send-ups of illustrious contemporaries and skewered, crank ancestors. There were Bishop's grim Nova Scotian parents, who gave her up, and their equally strange extended family and neighbors who took her in. Lowell was the quintessential American literary blueblood, unafraid of presenting his famous aunts and uncles as an abundant aviary, unfit not only for the practical world but also for their own self-created, eccentric atmospheres. He was a lost child among constantly aging yet seemingly pastless people. Living relics rolled their wheelchairs through the halls of Beacon Hill houses, weaving him into their underworld of shades, calling him by the names of the dead . . . Conversely, Bishop's letters have little sociological content, or even social observation. They are as vivid and colorful as her elaborately mannered but transparent lyrics. She escorts us over the Amazon's steaming tributaries and waterfalls, its mountains glistening with 'little floating webs of mist, gold spider-webs, iridescent butterflies . . . big pale blue-silver floppy ones' . . . For both of them, belief and knowledge and even hope were not given qualities of mind, but fragile constructs that could fall apart at any time; their letters, as well as their lyrics, propped up everything."—Richard Wirick, Bookslut

"In the realm of 20th-century American literature, the collected correspondence of Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell is among the most important sets of letters that we have between two poets. With style, humor, and candor, Words in Air charts the pair's gradual rise to fame in the literary world over thirty years, from their initial meeting at the New York apartment of poet-critic Randall Jarrell in 1947, until Lowell's sudden death from a heart attack in the back of a New York taxicab in 1977. At nearly 1,000 pages, this massive new volume will no doubt be an invaluable resource for scholars. It's also surprisingly entertaining for anyone interested in the daily minutiae and detailed observations of Elizabeth and Cal (as Lowell was affectionately called by friends)."—Jason Roush, The Gay & Lesbian Review

"Bishop and Lowell were two of the major poets of postwar America. From the time they met in 1947 at a party thrown by their mutual friend and poet, Randall Jarrell, through the end of Lowell's life in 1977, the pair—who saw each other rarely but considered themselves intimate friends—maintained a steady correspondence about literature and their turbulent lives and their own complicated, at times flirtatious friendship. Lowell was manic-depressive and embroiled in two volatile marriages, while Bishop also suffered depression and more than her share of loss, including the suicide of her longtime lover. Many of their now famous letters, previously available in separate volumes, appear here in one volume, their exchanges preserved in the order they were sent and received. Throughout this momentous volume, transcendence comes to these two often troubled writers through the shared experience of art that brought them together and sustained them: 'If only one could see everything that way all the time!,' writes Bishop in 1957, 'that rare feeling of control, illumination-life is all right, for the time being.'"—Publishers Weekly

Reviews from Goodreads

BOOK EXCERPTS

Read an Excerpt

INTRODUCTION

"WHAT A BLOCK OF LIFE"

In July 1965 the great mid-century American poet Robert Lowell (1917–1977), who had recently weathered a controversy that brought him into widely publicized opposition to the nation's...