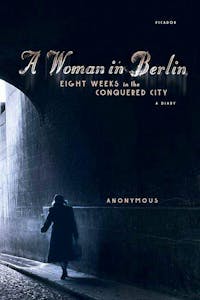

A Woman in Berlin

Eight Weeks in the Conquered City: A Diary

Download image

Download image

ISBN10: 0312426119

ISBN13: 9780312426118

Trade Paperback

288 Pages

$20.99

CA$27.99

An American Library Association Notable Book of the Year

A New York Times Book Review Editor's Choice

For eight weeks in 1945, as Berlin fell to the Russian army, a young woman, alone in the city, kept a daily record of her and her neighbor's experiences, determined to describe the common lot of millions.

Purged of all self-pity but with laser-sharp observation and bracing humor, the anonymous author conjures up a ravaged apartment building and its little group of residents struggling to get by in the rubble without food, heat, or water. Clear-eyed and unsentimental, she depicts her fellow Berliners in all their humanity as well as their cravenness, corrupted first by hunger and then by the Russians. And with shocking and vivid detail, she tells of the shameful indignities to which women in a conquered city are always subject—the mass rape suffered by all, regardless of age or infirmity. Through this ordeal, she maintains her resilience, decency, and fierce will to come through her city's trial, until normalcy and safety return.

At once an essential record and a work of great literature, A Woman in Berlin (translated by Philip Boehm) reveals not only a true heroine, sure to join other enduring figures of the twentieth century, but also gives voice to the rarely heard victim of war: the woman. This edition includes a foreword by Hans Magnus Enzenberger and an introduction by Anthony Beevor.

Reviews

Praise for A Woman in Berlin

"One of the most important documents to emerge from World War II . . . Anonymous died in 2001, but she remains officially unnamed, a private woman who has bequeathed us an extraordinary public legacy. Although the diary covers only two months—it ends as Berlin begins limping toward a semblance of normality—it is a richly detailed, clear-eyed account of the effects of war and enemy occupation on a civilian population . . . The most commonly accepted figure for rapes committed in Berlin during the first weeks of the Russian occupation is around 100,000 (calculated by hospitals to which the women turned for medical help). A Woman in Berlin shows us the actual experience behind those abstract numbers—how it felt; how one got through it (or didn't); how it brought its victory together, changing the way they saw men and themselves; the self-loathing ('I don't want to touch myself, can barely look at my body'); the triumph of just surviving. The book is graphic and unflinching, with the immediacy of all great diaries (we are always in the present), but what makes it so remarkable is its determination to see beyond the acts themselves. The rapists are not faceless; they have personalities, names . . . They have the contradictions of real people. They are brutal, naïve, even hungry for some kind of connection . . . Though the heart of the book, the rapes are by no means all of it. We are also given the feeling inside a bomb shelter, the breakdown of city life and civil society, the often surreal behavior of the enemy, soldiers' arms lined with looted wristwatches, the forced labor clearing out the rubble piles that marks the beginning of the road back . . . [Anonymous] is dispassionate and honest about Germany's responsibility for the war that has destroyed it, appalled at news of Nazi atrocities, thoughtful and open-minded, even about her oppressors . . . But the larger issues of the war are distant, available mostly by rumor. What she records instead is the world actually in front of her eyes, and here no detail escapes her—the stench of buildings where Russians have defecated wherever it suited them, the eerie silence of a whole city hunkering down, the behavior of her neighbors, often petty even in crisis. She has written, in short, a work of literature, rich in character and perception. It is dispiriting that shame or fear of social ostracism caused her to hide behind the label Anonymous (her fiance left her when he heard about the rapes), but even anonymously she has given us something that transcends shame and fear: the ability to see war as its victims see it. One evening, 'for the first time in three weeks I opened a book . . . But I had a hard time getting into it. I'm too full of my own images.' And we, too, will be full of those same images, for a long time to come."—Joseph Kanon, The New York Times Book Review

"Let Anonymous stand witness as she wished to: as an undistorted voice for all women in war and its aftermath whatever their names or nation or ethnicity. Anywhere."—Kai Maristed, Los Angeles Times Book Review

"[Anonymous's] journal earns a particular place in the archive of recollection. This is because it neither condemns nor forgives: not her countrymen, not their occupiers, and not, remarkably, herself . . . Anonymous writes a merciless account of what individuals can be faced with when all material and social props collapse. Not just their own, but those of an entire society, whose majority regards itself as ordered, justified, and comfortable. Never mind what it may be up to outside—or to the outsiders inside."—Richard Eder, The Boston Globe

"A Woman in Berlin enters terrain others have traveled, but does so confidently through a singular consciousness, becoming a tract essential for our often morally fuzzy times . . . it is destined to be a classic, given its depiction of one woman's candid response to an unambiguously horrible season, the vanquishing of Berlin by the Soviets over eight life-changing weeks in the spring and early summer of 1945 . . . From Herodotus and Josephus to the next-door teenage blogger, from Boswell and Papys to Alice James and Anne Frank, all keep a diary believing that such an odd little act will bring about some greater harmony, sanity or accurate account keeping. At the same time, not every diary makes the case, as A Woman in Berlin does so eloquently, for the authority of clear-eyed vision as a last precinct of the civilized, a sandbagged site of the individual, presenting history with an archetype of prevailing sanity . . . The translation is lucid, the heart of the writer unflinching . . . Anonymous uses her pen to fight against history's swords: The diary as an act of troubled conscious becomes one of the best ways for us to 'find our way to each other yet.'"—Edie Meidav, San Francisco Chronicle

"A brilliant and powerful work."—Scott McLemee, Newsday

"[A Woman in Berlin] is a story of hunger and rape, fear and humiliation, corruption and shame. Anonymous died in 2001. Her story will live as long as there is a readership for the literature of war, conquest, and the will to survive."—Sigrid Nunez, O, The Oprah Magazine

"A Woman in Berlin is first and foremost a riveting account of a military atrocity. Beyond that, it's a ruthless, almost farcical look at a capital's quick slide into a dog-eat-dog melee."—Rebecca Reich, The New York Observer

"[This] book should be embraced for the reason it was initially faulted. Its frank documentation of German suffering—the hunger and uncertainty as well as the widespread rape—illuminates a subject whose worldwide taboo is just beginning to subside."—Rebecca Tuhus-Dubrow, The Village Voice

"The publication of A Woman in Berlin: Eight Weeks in the Conquered City . . . shines considerable light on a hidden history of the war . . . An essential document."—Jonathan Shainin, Salon

"Spare and unpredictable, minutely observed and utterly free of self-pity, even darkly comic . . . [A Woman in Berlin] is destined for the short shelf of war classics . . . Anonymous describes herself only once, 'a pale-faced blonde always dressed in the same winter coat,' but she is unforgettable. The reader yearns to know what happened to her next. If I could, I'd lay flowers on her grave."—Karen R. Long, The Plain Dealer (Cleveland)

"An important contribution to [the] historical discourse . . . More than a simple day-by-day account of the gruesome reality in Berlin immediately after the end of the war. [The author's] poignant and insightful observations demonstrate a remarkable capacity to look beyond personal circumstances in order to discern the bigger picture . . . Her best writing emerges when she analyzes the impact of the war and subjugation on traditional gender roles . . . Her adroit descriptions of the people and their cellar rituals are so convincing that the reader can almost smell the damp air . . . As a historical and literary document, A Woman in Berlin deserves a place among the famous war diaries by Anne Frank and Victor Klemperer. This book is required reading for anyone who wants to gain an understanding of the trauma experienced by a defeated people at the end of World War II."—Bianka J. Adams, H-Net Book Review

"A devastating book. It is matter-of-fact, makes no attempt to score political points, does not attempt to solicit sympathy for its protagonist, and yet is among the most chilling indictments of war I have ever read. Everybody, in particular every woman, ought to read it."—Arundhati Roy, Booker Prize-winning author of The God of Small Things

"Complex, closely observed diary by a woman living in conquered Berlin at the end of WWII. A professional journalist and editor who died in 2001, the author documents with immediacy her struggle to survive at the closing stages of the war. Originally published in 1953, the diary chronicles in the present tense the lives of Germans in the spring of 1945 as 1.5 million Soviet soldiers advance through bombed-out Berlin. The first interactions are relatively calm. Russians happily ride stolen bicycles through the streets; the author hears and sees their 'friendly voices, good-natured faces.' This period quickly ends with mass rape of German women, including the diarist. After describing in detail the psychological and physical toll of rape, Anonymous decides, 'I'm alive, aren't I? Life goes on!' Many women adopt gallows humor, saying, 'Better a Russki on top than a Yank overhead.' Using a strategy adopted by many, the author seduces a high-ranking Russian officer: 'I have to find a single wolf to keep away the pack,' she explains. Several of these arrangements not only provide her with some protection, but also much-needed food and supplies. Anonymous writes of her neighbors' collective shame about their complicity with Nazism and quotes a German refugee, brutalized at the Czech border, who says wearily, 'We can't complain. We brought it on ourselves.' But she also notes how quickly many of her compatriots pull a hollow about-face and reject Hitler. A tireless observer, she pinpoints wartime relationships and small revealing scenes: the eeriness of vanished sparrows, the progress of gardeners tending their plots between bombings, a boy dreamily asking his mother if they can eat an emaciated horse, Berliners repeating with scornful irony the prewar propaganda catchphrase, 'For all of this we thank the Führer.' Frank and affecting, a remarkable piece of war literature."—Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

BOOK EXCERPTS

Read an Excerpt

From A Woman in Berlin:

Friday, 11 pm, by the light of an oil lamp, my notebook on my knees. Around 10 pm there was a series of bombs. The siren started right in screaming. Apparently it has to be worked by hand now. No light. Running...

MEDIA

Watch

A Woman in Berlin Official Movie Trailer

Watch this video and see the official trailer for the film adapation of A Woman in Berlin, set in 1945 during the Red Army invasion of Berlin.

Share This